This is how a fleet of drones are planting almost 20,000 seed pods every day.

Since man alone cannot change the consequences of climate change, he will have to rely on technology to try to alleviate damage that already seems inevitable, and now they will rely on a fleet of drones that they are going to plant. more than 1 billion trees in just eight years.

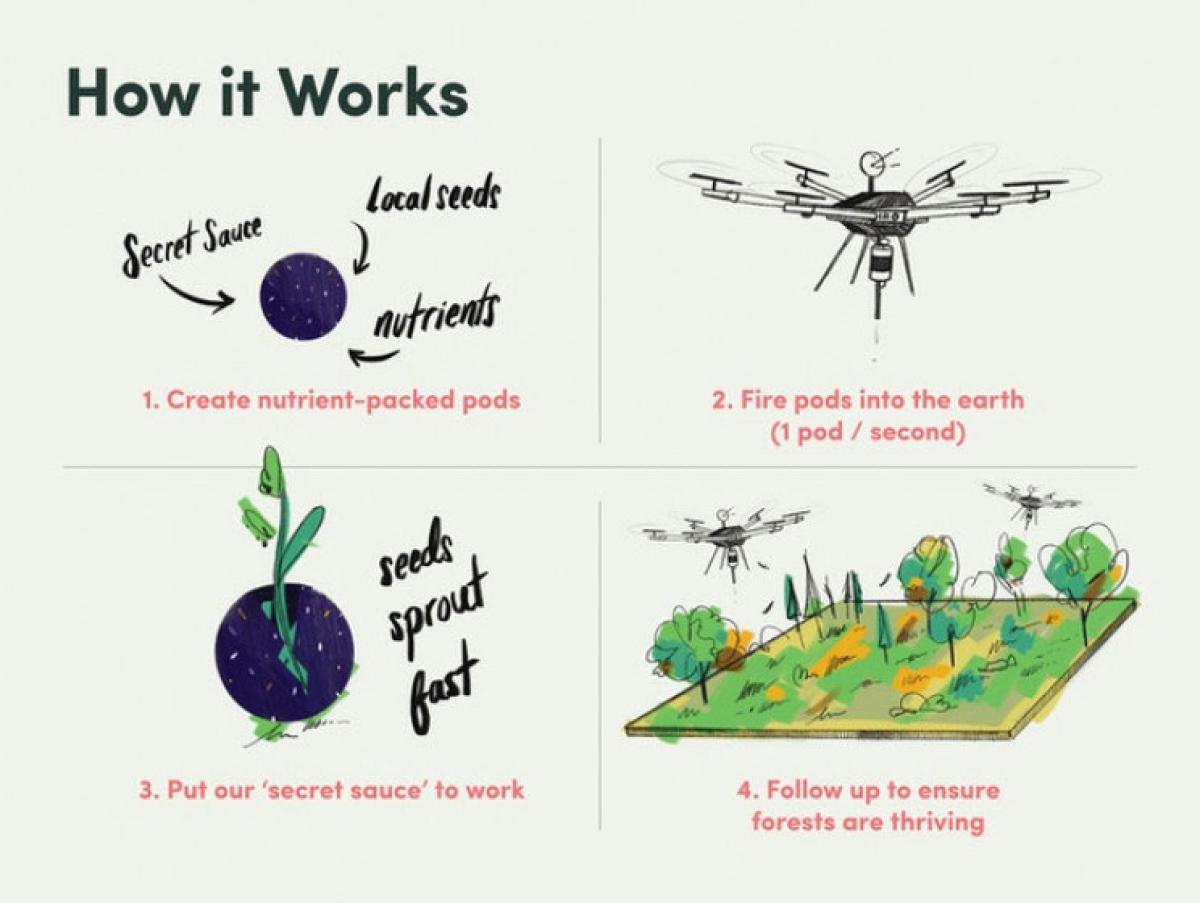

Now Toronto-based startup Flash Forest is going to use drones to plant trees 10 times faster than workers with the goal of planting 1 billion trees by 2028. Flash Forest combines the use of drones with specially-designed pods and an accelerated seed germination process. According to Flash Forest, its technology can plant trees 10 times faster than a single worker and at a cost that is 80 percent cheaper than traditional tree planting methods.

The company, like a handful of other startups that are also using tree-planting drones, believes that technology can help the world reach ambitious goals to restore forests to stem biodiversity loss and fight climate change.

“We are a Canadian drone reforestation company that modifies drones to fire rapidly-germinating tree seeds into the soil,” says Flash Forest. “We merge technology, software and ecological science to surpass traditional tree-planting efforts and rapidly accelerate global reforestation efforts. With our ambitious goal of planting 1 billion trees by 2028.”

The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change says that it’s necessary to plant 1 billion hectares of trees—a forest roughly the size of the entire United States—to limit global warming to 1.5 degrees Celsius. Existing forests need to be protected while new trees are planted; right now, that isn’t working well. “There are a lot of different attempts to tackle reforestation,” says Flash Forest cofounder and chief strategy officer Angelique Ahlstrom. “But despite all of them, they’re still failing, with a net loss of 7 billion trees every year.”

Drones don’t address deforestation, which is arguably an even more critical issue than planting trees, since older trees can store much more carbon. But to restore forests that have already been lost, the drones can work more quickly and cheaply than humans planting with shovels. Flash Forest’s tech can currently plant 10,000 to 20,000 seed pods a day; as the technology advances, a pair of pilots will be able to plant 100,000 trees in a day (by hand, someone might typically be able to plant around 1,500 trees in a day, Ahlstrom says.) The company aims to bring the cost down to 50 cents per tree, or around a fourth of the cost of some other tree restoration efforts.

The seeds are already sprouted before they’re inserted into the ground, promising a more successful growth pattern and robust rooting system. Following the planting, the team will follow-up the process with a spraying drone to provide nitrogen and other nutrients to the seedlings. Furthermore, an additional mapping drone is used to keep an eye on the process of the plants’ growth. The team hopes to plant eight different species to generate healthy ecosystems, while also planting enough trees to offset North American carbon emissions.

The Flash Forest pods use less water than traditional planting methods and can be created in mass quantities within just 30 days. This allows the team to plant trees much faster and at a huge economical savings, compared to the use of seedlings that often require 12 to 24 months in a nursery before they can be planted successfully.

“This year we planted eight deciduous and coniferous species local to Southern Ontario,” says Flash Forest. “We can easily fill our pods with seeds of virtually any tree species (except for acorns and a few of the larger exceptions). If interested, we can also plant any flora that’s appropriate for an ecosystem in its succession period.”

When it begins work at a site, the startup first sends mapping drones to survey the area, using software to identify the best places to plant based on the soil and existing plants. Next, a swarm of drones begins precisely dropping seed pods, packed in a proprietary mix that the company says encourages the seeds to germinate weeks before they otherwise would have. The seed pods are also designed to store moisture, so the seedlings can survive even with months of drought. In some areas, such as hilly terrain or in mangrove forests, the drones use a pneumatic firing device that shoots seed pods deeper into the soil. “It allows you to get into trickier areas that human planters can’t,” Ahlstrom says.

After planting, the company returns to track the progress of the seedlings. “Depending on the project, we’ll go back two months after, and then a year or two after, and then three to five years after” to make sure the trees are actually sequestering as much carbon as they planned, she says. “If we fall under a threshold plant goal of a certain number of trees, we’ll go back and ensure that we are hitting our goal.” Because the company chooses native species and uses its seed pods to protect the seeds from drought, the process doesn’t typically require work from humans to keep the seedlings alive; instead, the strategy is to plant a large number of trees and let some naturally survive.

Each planting is using about four species, with a goal of eight. “We very much prioritize biodiversity, so we try to plant species that are native to the land as opposed to monocultures,” says Ahlstrom. “We work with local seed banks and also take into account that the different changes that climate change brings with temperature rise, anticipating what the climate will be like in five to eight years when these trees are much older and have grown to a more mature stage, and how that will affect them.”

After launching the company in early 2019, the small team had a working prototype by the middle of the year and ran a pilot test in August, followed by larger tests in September and October. So far, Ahlstrom says, they’ve seen high rates of survival in controlled studies, and are hoping to replicate those in real world settings.

After the current planting near Toronto and another in British Columbia, the company will begin a restoration project in Hawaii later in the year, with plans to plant 300,000 trees there. It’s also planning tree-planting pilots in Australia, Colombia, and Malaysia. In some cases, funding comes from forestry companies, government contracts, or mining companies that are required to replant trees; in other cases, the startup plants trees for companies that offer tree-planting as a donation with the sale of products, or for landowners who can get a tax break, in some areas, for planting trees. “There’s a lot of philanthropy around it, and then also just a solid business model with a desperate need and demand to plant trees,” Ahlstrom says.

To quickly plant around a trillion trees—a goal that some researchers have estimated could store more than 200 gigatons of carbon—Flash Forest argues that new technology is needed. In North America, trees need to grow 10-20 years before they efficiently store carbon, so to address climate change by midcentury, trees need to begin growing as quickly as possible now. “I think that drones are absolutely necessary to hit the kind of targets that we’re saying are necessary to achieve some of our carbon sequestration goals as a global society,” she says. “When you look at the potential for drones, we plant 10 times faster than humans.”