February may be the shortest and coldest month of the year. But for many, it is a time to give special recognition to often overlooked aspects of world history (Black History Month) and recognize what may be the single greatest threat to health in the world. For many, February is also known as Heart Health Month, and 2022 will be the 58th consecutive year it is recognized.

Cardiovascular disease is a global problem that claims the lives of more people a year than cancer, strokes, or other prevalent diseases. Luckily, advanced research is leading to effective solutions for improving cardiovascular health. A conspicuous example is how machine learning and artificial intelligence are allowing for faster diagnoses, improved accuracy, and earlier detection.

A good example is Eko, an Oakland, California-based medical technology company founded in 2015 by graduates from the University of California Berkeley dedicated to leveraging AI to provide cost-effective screenings for cardiovascular and lung disease. In its mission to make medical care more accessible, they have created a line of “smart stethoscopes.”

These allow doctors to visualize, record, share and analyze heart sounds using a cloud-based algorithm, and at a fraction of the cost of conventional cardiograms and ultrasounds. As Eko CSO Jason Bellet told Interesting Engineering via Zoom:

“We’ve built the first ‘smart stethoscope’ that amplifies sound and reduces background noise, but also pairs with a software platform that allows clinicians to engage with heart and lung sounds for the first time in a digital format – save it, share it, and analyze it, using our algorithms.”

This technology could save the lives of (literally) millions of people worldwide, especially those who live in underserved communities and developing nations.

A global problem

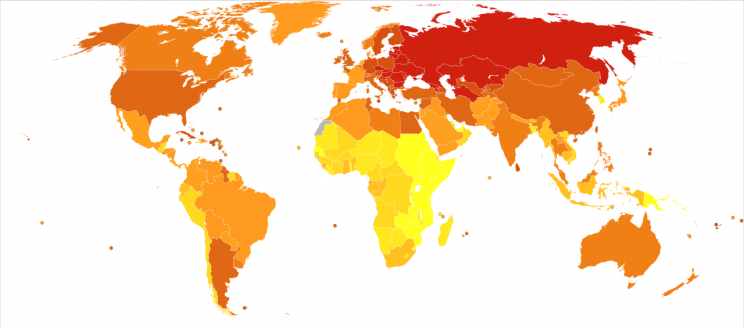

According to the Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), roughly 950,000 Americans on average die every year from cardiovascular disease (CVD). What’s more, the toll of CVD is felt disproportionately by people of color, rural residents, and those living in poverty. There’s also a predictable disparity in heart disease between people living in developed nations and the developing world.

By definition, cardiovascular diseases are a group of disorders involving the heart and blood vessels and include coronary heart disease, cerebrovascular disease, rheumatic heart disease, and other conditions. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), CVDs are the leading cause of death globally and account for an estimated 17.9 million deaths a year (or 32 percent of all deaths worldwide).

Of these deaths, roughly 85 percent were due to heart attack and stroke, and one-third of these deaths occurred prematurely in people under 70 years of age. On top of that, over three-quarters of annually-recorded CVD deaths (~13.5 million) take place in low and middle-income countries. So, while the problem is global, there are disparities based on wealth and access to medical services.

In the developed world, the problem is much the same. According to stats compiled by the CDC for 2020, heart disease accounted for 696,962 deaths in the U.S. alone. This made CVDs the leading cause of death, beating out cancer (598,932) and COVID-19 (350,831). What’s more, according to some measurements, at least 48 percent of adults in the U.S. have some form of CVD, including high blood pressure, most of whom are from low- and middle-income families.

This prevalence of heart disease is accompanied by the problem of cost. According to a 2017 report by the American Heart Association (AHA), the projected costs of treating heart disease in the U.S. will reach $1 trillion by 2035. This problem arises because of the high price of screenings, which require expensive machinery that only large hospitals can afford.

While there are several risk factors associated with CVDs – such as an unhealthy diet, physical inactivity, and tobacco, alcohol, and drug use – other factors also play a role. These include high blood pressure, blood glucose levels, raised blood lipids, and genetic factors. Hence, early detection is critical and has been shown to reduce the risk by 80 percent.

A problem of access

As noted, access to medical care is limited by poverty and a lack of infrastructure. For those who can afford medical care, a standard heart health check involves an electrocardiogram (ECG or EKG), which requires large and expensive machinery and special technicians. Typically, the procedure can cost between $500-$3,000 for uninsured patients (in the U.S.), and the waiting lists are often long.

An echocardiogram (which relies on ultrasound technology) is a relatively low-cost and non-invasive method, but this advanced technology is only available in certain parts of the world. This situation has been helped thanks to the invention of portable ECG and EKG devices, but cost factors also limit these.

This makes early detection very challenging in environments where hospitals are less common – like developing nations and rural areas. The only other method available to doctors and screeners is the stethoscope. In this time-honored method, doctors listen to a patient’s heart for indications of arrhythmia and abnormalities.

This device is internationally recognized as an icon of medicine and is also the most widely used for heart health screenings. Because of its low-cost and non-invasive nature, the stethoscope remains the workhorse of medical practitioners. However, the device’s simplicity also limits its effectiveness, which raises the question: is it time to update this icon of medicine?

Updated for the digital age

Eko was founded in 2014 by Connor Landgraf and Jason Bellet, the company’s CEO and CSO (respectively). Before launching this biotech enterprise, Landgraf was a researcher with the Biologically-inspired Photonics Optofluidics Electronics Technology & Science (BioPOETS) laboratory at UC Berkeley and a Trustee with the philanthropic Berkely Foundation.

Bellet is also a UC Berkeley alumni and a graduate of its Walter A. Haas School of Business. Along with a team of bioengineering and mechanical engineering alumni, they founded the company because they were fascinated with the stethoscope. As Bellet recounted the experience:

“We talked to a number of cardiologists, and they pointed to their stethoscopes, and they said, ‘Listen, this is the icon of medicine. It’s worn around the neck of 30 million clinicians. But it hasn’t been innovated on in over 200 years.’ It’s essentially a rubber tube with a metal chest piece and amplifies sound so the clinician can hear and ultimately screen for cardiovascular disease.

“Despite all the innovation and engineering that we’ve seen in cardiology, with the electrocardiogram and echocardiogram, the stethoscope is still what we rely on to screen billions of patients a year. Because it’s low cost, it’s non-invasive, and you can do it in seconds in any physical exam. But it’s pretty inefficient because it relies on the subjectivity of the human ear, and it’s difficult to use in loud environments.”

From this, said Bellet, a lightbulb went off in their minds, and they began contemplating how the stethoscope could be brought into the digital age. Paired with wireless technology, cloud computing, and machine learning algorithms, they believed they could update the stethoscope in a way that honored its ubiquity and convenience while taking some of the subjectivity out of it.

“When we think of one in four people being diagnosed or undiagnosed with cardiovascular disease, that requires a solution from a diagnose and detection perspective, that can pretty much reach every patient,” he said. “And the best tool to do that, from our perspective, is the stethoscope because it can be integrated into every single physical exam.”

The idea behind the “smart stethoscopes” is pretty straightforward. The stethoscope picks up heart sounds which are then wirelessly streamed to the Eko Platform using a HIPAA*-compliant app. There are multiple versions of the “smart stethoscope,” including a standard digital model, one with an integrated ECG, and a digital adaptor that can be attached to an analog stethoscope.

Once received by the Eko platform, an Eko algorithm then analyzes this data for signs of arrhythmia, low-ejection fractions (LEF), and other indications of heart problems. The team spent years gathering data on heart and lung sound screenings at UC Berkeley to create this algorithm.

“To build algorithms around heart and lung sound screening, you have to have a large dataset of digital heart sounds and lung sounds,” said Bellet. “So, we spent the first many years of our company actually just building the digital stethoscope and collecting the dataset since the dataset did not exist prior to our technology.”

The team then partnered with the Mayo Clinic, Northwestern Medicine, and the University of California San Francisco (UCSF) to build condition-specific annotated datasets that resulted in different algorithms. Additional assistance was provided by the Stanford National Accelerator Laboratory, 3M, and numerous health care venture capital firms.

According to a recent independent study by the UK National Health Services, the algorithm has been validated as the first to successfully screen for heart disease within 15 seconds of an initial doctor’s visit. But most important of all, these smart stethoscopes allow for accurate screening at a fraction of the cost of an ECG/EKG or echocardiogram.

“What’s key to that is getting some of these tools to a cost point and accessibility point that they can be used by primary care doctors,” said Bellant. “Because the reality is, we could have great diagnostic tools, but if it’s multiple thousands of dollars and interferes with the average clinician’s workflow, it’s just not going to be implemented. If you can’t deploy it, it doesn’t matter.”

From a cost perspective, the price point of these devices allows for thousands of people a year to be screened for a marginal cost compared to a twelve lead EKG or an ultrasound. Said Bellant:

“Our most expensive stethoscope is $349. We have an option for $199 that, put around the neck of one clinician, can screen five thousand to ten thousand patients a year. The average clinician sees anywhere between two to three thousand patients in any given year. So you put two or three of these in a community, and you can screen the entire community over the course of a couple of years.”

*Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA).

Addressing disparities

As noted, there is an apparent disparity in health outcomes for different parts of the world. Within developed nations like the U.S., this disparity includes a gap between urban and rural areas and the insured and uninsured. And there is a racial dimension to this disparity, where poverty and lack of access are felt disproportionately.

The Biden Administration released a proclamation on the White House official website in honor of Heart Health Month. In addition to highlighting the progress made in the treatment of heart disease and its risk factors, the proclamation also acknowledged how the burden is felt unevenly:

“Despite the significant progress we have made, heart disease continues to exact a heartbreaking toll — a burden disproportionately carried by Black and brown Americans, American Indians and Alaska Natives, and people who live in rural communities. Cardiovascular diseases — including heart conditions and strokes — are also a leading cause of pregnancy-related deaths, which are highest among women of color.”

As Bellet explained, this is one of the things that he and his colleagues are most excited about with this technology:

“There are communities in Africa and Haiti and a whole host of underserved areas around the world that – from a medical infrastructure perspective – are underdeveloped. They are averaging one EKG machine per one million people. And these are populations where they have a higher propensity for developing cardiovascular disease due to lifelong healthcare access issues.

In many underdeveloped parts of the world, doctors and medical equipment are not readily available. In these regions, nurses, nurse-midwives, healthcare workers, and volunteers will go into communities to set up clinics and provide services free of charge. This includes cardio health screenings that, says Bellant, are limited by some key factors:

“Part of the problem is, they don’t have the trained ear and expertise very often to pick up the structural heart disease and heart failure that you would get in a number of more developed care settings. By bringing the ears of a cardiologist, using A.I., to the stethoscope of any healthcare worker in rural Africa, rural Haiti, or the rural United States, we have the ability to ‘democratize’ access to specialty-grade cardiac screening.”

Looking ahead, Eko hopes to expand its platform to include algorithms that will allow for the early detection of pulmonary (lung) disease. In the meantime, they have donated $300,000 in software and products to U.S. clinics that serve uninsured and underserved communities and outfitted 150,000 clinicians with their stethoscopes (mainly in the U.S.).

But as Bellet said, this is just the beginning. There are currently an estimated 30 million stethoscope users around the world, he said, each of whom screens dozens of patients a day, adding to up to billions of patients screened for heart disease every year:

“We envision a future where a patient in every single physical exam will have their heart and lungs examined using our A.I.-powered stethoscope to screen for a variety, a panel of life-threatening conditions that often go undetected. We’re going to do this by helping the clinician, not replacing them, identify things that are often hard to hear.”

“If we can bring that technology into the digital age, we have the power to help extend the lives and improve the outcomes of patients with heart and lung disease.”

The future of medicine?

Healthcare has been largely focused on creating therapeutics or treatments designed to alleviate problems. Research has led to extraordinary breakthroughs in stem-cell therapy, gene therapy, DNA sequencing, cancer treatments, bioprinting, and new drug therapies in the last few decades.

But without early detection and better screening methods, even the most amazing medical advancements will have limited outcomes. Hence, there has been renewed interest and investment in diagnostics and assessment in recent years that are particularly cost-effective compared to more traditional approaches (i.e., large and expensive machinery).

In this respect, the more A.I. is integrated into the workflow to help clinicians diagnose heart conditions early on, the better. In terms of advanced research, there are numerous other examples of A.I. applications for heart health. The Mayo Clinic, which helped Eko develop its algorithms, also leverages A.I. to improve treatment outcomes.

For example, A.I. techniques allowed their researchers to develop a new screening tool for Left Ventricular Dysfunction (LVD) in people without noticeable symptoms. In trials, the tool identified people at risk of left ventricular dysfunction 93 percent of the time. They’ve also developed a low-cost test for the early detection of a weak heart pump, which can lead to heart failure if left untreated.

The Clinic has also shown how A.I.-guided ECGs can detect atrial fibrillation (heart arrhythmia) before evident symptoms. Part of what makes the Mayo Clinic well-suited to A.I. research is its long history of high-volume patient care, which has generated a massive database to draw from.

Johnson & Johnson is also researching A.I. through their JLABS incubator division. Using billions of clinical data points (images of coronary arteries) and the results of coronary angiograms, they have created a platform called CorVista™, which detects coronary artery disease (CAD) using pattern recognition.

Similarly, in 2017, the global tech conglomerate Alphabet announced the launch of Google A.I. to “bring the benefits of A.I. to everyone.” The following year, Google’s health technology subsidiary (Verily Life Sciences) released a study that described how they had developed an algorithm to search for symptoms of cardiovascular disease that manifest themselves in the eye (retinal fundus).

In 2018, the Canadian biotech company CardiA.I. began developing A.I.-driven solutions to improve cardiovascular health. On the one hand, they train machine-learning algorithms to analyze data from Holter monitors (a portable ECG). On the other, they are developing A.I. to examine nuclear heart scans, CT scans, coronary angiograms, echocardiograms, or other images.

Recent research at the University of Oxford has resulted in an A.I.-based algorithm that can detect potential heart problems based on a patient’s fat radiomic profile (FRP). The algorithm can predict possible future heart attacks by spotting signs of inflammation, scarring, and other changes in the perivascular space lining blood vessels.

Beyond heart health, A.I. is also being integrated into other aspects of medical care, such as analyzing blood and stool samples. In all cases, the goal is to use massive data sets (which have become the norm in the digital age) to train machines to spot problems with greater speed and efficiency, thus cutting costs and freeing doctors to do less laborious tasks.

By combing A.I. with cloud computing, big data, and miniaturization, companies like Eko are bringing the benefits of innovative technology to underserved communities. As with so many other aspects of the modern age, the goal is to leverage technological breakthroughs to lower costs and improve access.

But nothing less than universal access will do when it comes to medicine!