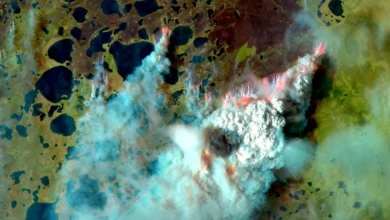

Lead Image: The plant, Ambrosia artemisiifolia (also known as ragweed), has already spread all the way to Denmark.

In order to comprehend the spread of the invasive North American plant known as ragweed, researchers looked into its genes.

One of the world’s biggest environmental issues is alien species. However, scientists often are unable to explain why or how these species are able to spread so rapidly.

“Invasive species are a key factor in the crisis that is affecting biological diversity now,” says Michael D. Martin, professor of evolutionary genomics at the Norwegian University of Science and Technology’s (NTNU) University Museum.

The Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (IPBES) has identified the five most serious threats to species diversity throughout the world. Land use change takes the lead, followed by direct resource exploitation, climate change, and pollution.

The fifth concern, however, is one that many people may not have considered: alien species that move into places where they do not belong. However, scientists know they pose a big problem.

However, it is uncertain how and why alien species spread so rapidly. As a result, an international research group comprised of some of the world’s best genetic experts has taken up the case of common ragweed (Ambrosia artemisiifolia). Their findings were recently published in the journal Science Advances.

Why do weeds spread?

Native to temperate regions of North America, common ragweed was accidentally introduced to Europe in the 1800s through imported seeds and contaminated horse feed. In recent years, it has spread throughout a considerable portion of the continent. Today, contaminated bird feed is a major source of introduction, therefore if you feed birds outside with imported seeds, you should sort out the ragweed seeds first.

Many alien species, fortunately, die before they can do any harm because they are unable to establish and adapt to new surroundings. So what makes common ragweed able to thrive? Their genes hold the key.

“We examined the genetic material in 655 specimens of common ragweed, of which 308 were taken from historical plant collections in herbaria. Some of them were as much as 190 years old and are from the time the plant got first introduced to Europe,” says Vanessa C. Bieker, an expert in evolutionary genetics at the NTNU University Museum.

In this way, the researchers were able to follow how common ragweed has evolved since the plant arrived in Europe. This information provided answers that helped them better understand what led to the enormous spread today.

But first, a little information about why alien species are something we should worry about.

Causing problems worldwide

Alien species cause problems over large parts of the world. In Norway, invasive threats include the salmon parasite Gyrodactylus salaris, mink, Sitka spruce, garden lupines, American lobster, the pond weed Elodea canadensis, red king crab, Canada goose, and giant hogweed.

Human influence on nature is often at the core of the problem. The Homo sapiens population will surpass eight billion this year. Over the past 50 000 years, spreading species to parts of the globe where they do not belong is one way human beings have changed the planet.

These alien species can outcompete species that already exist in an area. Sometimes they simply eat the local species. Other times they eat their food. They take over the habitats of species that are unable to stand up to the invaders’ ability to reproduce or utilize the resources in the area.

Common ragweed grows quickly and gets big and can thus outcompete local species.

Rabbits and cats

A famous example is the rabbits of Australia, where Europeans released a few rabbits on their newly discovered continent to make it more homey and to have something to hunt. But in Australia, the rabbits had no natural enemies that could keep the population in check.

Half a billion rabbits and enormous destruction of nature later, the rabbits were no longer so pleasant. Even after massive disease outbreaks and intensive efforts to control the population, Australia still has a few hundred million rabbits, not to speak of more than a million wild camels, 200 million toads, and a few million foxes and wild cats.

Cats are one of the really big threats to birds and other animals worldwide. In the USA they kill up to four billion birds and more than 20 billion mammals annually, while in Norway outdoor cats kill about seven million birds. If you really want to help the environment, you should keep your cat inside – and get it neutered, too.

Tougher plants in Europe

So, getting back to Europe and common ragweed. The research group found answers that can explain why this plant has been so successful.

“The invasive populations in Europe favor the development of genes that contribute to their defense, like ones against pathogens that trigger disease,” says Vanessa C. Bieker.

In Europe, common ragweed might have evolved in such a way that the plant became more resistant to local threats.

Natural selection meant that hardy plants had a great advantage and multiplied more often than less hardy specimens. This spread to the offspring who carried the advantage forward. Today, the tougher plants have completely taken over.

Other species contributed to the spread

Common ragweed also received help from outsiders along the way. Common ragweed reproduces sexually and made up for the lack of partners on a new continent by going outside its own species.

“We discovered that the plant hybridized in Europe with closely related species that were introduced around the same time,” says Michael Martin.

This behavior meant that common ragweed did not need to have another common ragweed plant nearby for the plant to gain a foothold as pollen from close relatives could be used to produce seeds. This is especially useful in the early stages of the introduction when population sizes are small.

Spread all the way to Denmark

The plant might also have escaped enemies it had in North America by coming here. In its natural home range, it was susceptible to bacterial pathogens attacking it.

In Europe, the local bacteria had not co-evolved with common ragweed, and so they posed no immediate threat. The invading plant could use more energy on growth and reproduction instead of on defense, which in turn gave it an advantage over the local plants.

Common ragweed is also a problem in parts of its home continent of North America. Agriculture and settlers helped spread the plant to parts of America where the plant is not native. You can read more about that here.

Denmark is currently the northern limit for the common ragweed, and it is now becoming more established there. The plant is currently not a threat in Norway, probably because of the country’s harsh climate.

That’s good for now – and also for pollen allergy sufferers who might otherwise dread a season lasting until November. We will see what happens if climate change strikes with warmer winters. Maybe putting up with our cold winters and freezing a little now and then isn’t so bad after all.

Reference: “Uncovering the genomic basis of an extraordinary plant invasion” by Vanessa C. Bieker, Paul Battlay, Bent Petersen, Xin Sun, Jonathan Wilson, Jaelle C. Brealey, François Bretagnolle, Kristin Nurkowski, Chris Lee, Fátima Sánchez Barreiro, Gregory L. Owens, Jacqueline Y. Lee, Fabian L. Kellner, Lotte van Boheeman, Shyam Gopalakrishnan, Myriam Gaudeul, Heinz Mueller-Schaerer, Suzanne Lommen, Gerhard Karrer, Bruno Chauvel, Yan Sun, Bojan Kostantinovic, Love Dalén, Péter Poczai, Loren H. Rieseberg, M. Thomas P. Gilbert, Kathryn A. Hodgins and Michael D. Martin, 24 August 2022, Science Advances.

DOI: 10.1126/sciadv.abo5115