This ain’t your grandma’s fridge magnet. It’s much, much more!

An exotic form of magnetism has been discovered and linked to an equally exotic type of electrons, according to scientists who analyzed a new crystal in which they appear at the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST). The magnetism is created and protected by the crystal’s unique electronic structure, offering a mechanism that might be exploited for fast, robust information storage devices.

The newly invented material has an unusual structure that conducts electricity but makes the flowing electrons behave as massless particles, whose magnetism is linked to the direction of their motion. In other materials, such Weyl electrons have elicited new behaviors related to electrical conductivity. In this case, however, the electrons promote the spontaneous formation of a magnetic spiral.

“Our research shows a rare example of these particles driving collective magnetism,” said Collin Broholm, a physicist at Johns Hopkins University who led the experimental work at the NIST Center for Neutron Research (NCNR). “Our experiment illustrates a unique form of magnetism that can arise from Weyl electrons.”

The findings, which appear in Nature Materials, reveal a complex relationship among the material, the electrons flowing through it as current and the magnetism the material exhibits.

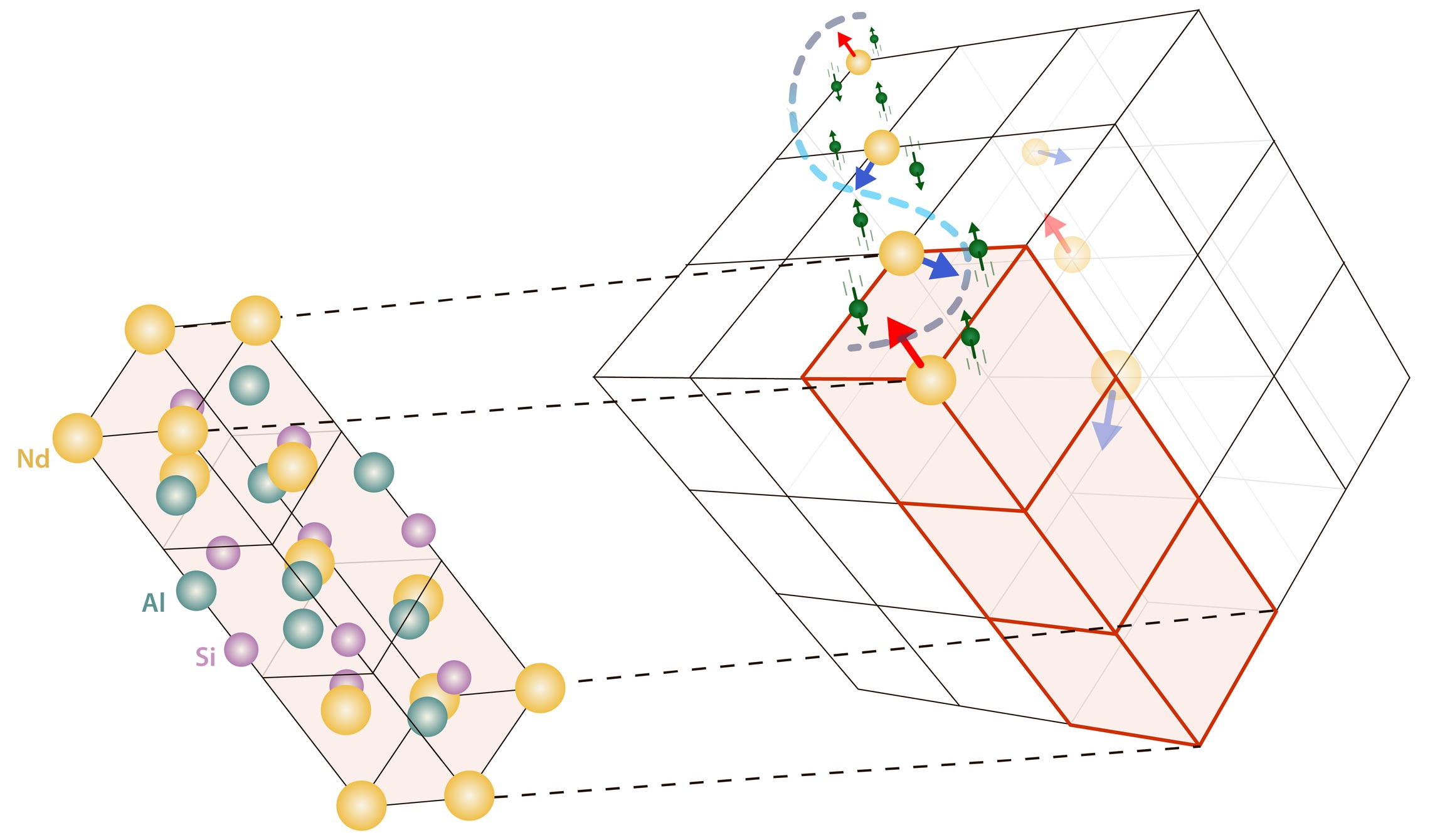

In a refrigerator magnet, we sometimes imagine each of its iron atoms as having a bar magnet piercing it with its “north” pole pointing in a certain direction. This image refers to the atoms’ spin orientations, which line up in parallel. The material the team studied is different. It is a “semimetal” made of silicon and the metals aluminum and neodymium. Together these three elements form a crystal, which implies that its component atoms are arranged in a regular repeating pattern. However, it is a crystal that breaks inversion symmetry, meaning that the repeating pattern is different on one side of a crystal’s unit cells — the smallest building block of a crystal lattice — than the other. This arrangement stabilizes the electrons flowing through the crystal, which in turn drive unusual behavior in its magnetism.

The electrons’ stability shows itself as a uniformity in the direction of their spins. In most materials that conduct electricity, such as copper wire, the electrons that flow through the wire have spins that point in random directions. Not so in the semimetal, whose broken symmetry transforms the flowing electrons into Weyl electrons whose spins are oriented either in the direction the electron travels or in the exact opposite direction. It is this locking of the Weyl electrons’ spins to their direction of motion — their momentum — that causes the semimetal’s rare magnetic behavior.

“Our experiment illustrates a unique form of magnetism that can arise from Weyl electrons.” — Collin Broholm, a physicist at Johns Hopkins University

The material’s three types of atoms all conduct electricity, providing steppingstones for electrons as they hop from atom to atom. However, only the neodymium (Nd) atoms exhibit magnetism. They are susceptible to the influence of the Weyl electrons, which push the Nd atom spins in a curious way. Look along any row of Nd atoms that stretches diagonally through the semimetal, and you will see what the research team refers to as a “spin spiral.”

“A simplified way to imagine it is the first Nd atom’s spin points to 12 o’clock, then the next one to 4 o’clock, then the third to 8 o’clock,” Broholm said. “Then the pattern repeats. This beautiful spin ‘texture’ is driven by the Weyl electrons as they visit neighboring Nd atoms.”

It took a collaboration among many groups within the Institute for Quantum Matter at Johns Hopkins University to reveal the special magnetism arising in the crystal. It included groups working on crystal synthesis, sophisticated numerical calculations and neutron scattering experiments.

“For the neutron scattering, we greatly benefited from the extensive amount of neutron diffraction beam time that was available to us at the NIST Center for Neutron Research,” said Jonathan Gaudet, one of the paper’s co-authors. “Without the beam time, we would have missed these beautiful new physics.”

Each loop of the spin spiral is about 150 nanometers long, and the spirals only appear at cold temperatures below 7 K. Broholm said that there are materials with similar physical properties that function at room temperature, and that they might be harnessed to create efficient magnetic memory devices.

“Magnetic memory technology like hard disks usually requires you to create a magnetic field for them to work,” he said. “With this class of materials, you can store information without needing to apply or detect a magnetic field. Reading and writing the information electrically is faster and more robust.”

Understanding the effects that the Weyl electrons drive also might shed light on other materials that have brought consternation to physicists.

“Fundamentally, we might be able to create a variety of materials that have different internal spin characteristics — and perhaps we already have,” Broholm said. “As a community, we have created many magnetic structures we don’t immediately comprehend. Having seen the special character of Weyl-mediated magnetism, we may finally be able to understand and use such exotic magnetic structures.”

Reference: “Weyl-mediated helical magnetism in NdAlSi” by Jonathan Gaudet, Hung-Yu Yang, Santu Baidya, Baozhu Lu, Guangyong Xu, Yang Zhao, Jose A. Rodriguez-Rivera, Christina M. Hoffmann, David E. Graf, Darius H. Torchinsky, Predrag Nikolić, David Vanderbilt, Fazel Tafti and Collin L. Broholm, 19 August 2021, Nature Materials.

DOI: 10.1038/s41563-021-01062-8

Data for the study was obtained in part with the multi-axis crystal spectrometer (MACS) instrument, which is part of the Center for High Resolution Neutron Scattering (CHRNS), a national user facility jointly funded by NCNR and the National Science Foundation (NSF).