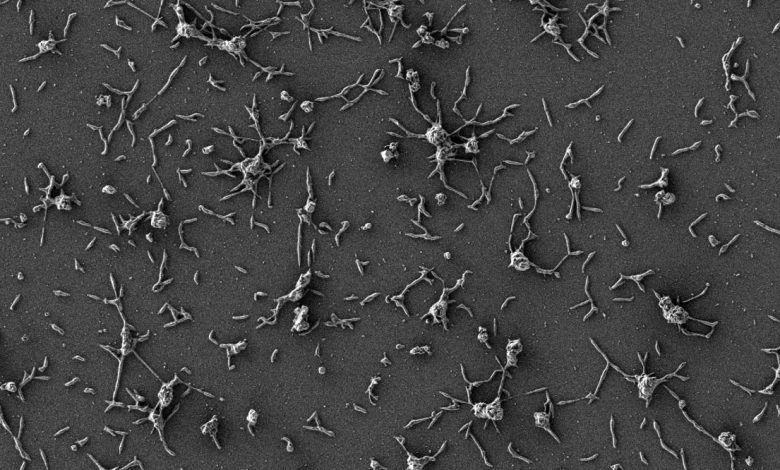

Lead image: Scanning electron microscope image of Mycoplasma pneumoniae cells, small bacteria that are naturally adapted to the human lung. Credit: María Lluch/CRG

Experimental treatment dissolves antibiotic-resistant biofilms in mice.

Researchers at the Center for Genomic Regulation (CRG) and Pulmobiotics S.L have created the first ‘living medicine’ to treat antibiotic-resistant bacteria growing on the surfaces of medical implants. The researchers created the treatment by removing a common bacteria’s ability to cause disease and repurposing it to attack harmful microbes instead.

The experimental treatment was tested on infected catheters in vitro, ex vivo, and in vivo, successfully treating infections across all three testing methods. According to the authors, injecting the therapy under the skin of mice treated infections in 82% of the treated animals.

The findings are an important first step for the development of new treatments for infections affecting medical implants such as catheters, pacemakers, and prosthetic joints. These are highly resistant to antibiotics and account for 80% of all infections acquired in hospital settings.

The study is published today (October 6, 2021) in the journal Molecular Systems Biology. This work has been supported by the “la Caixa” Foundation through the CaixaResearch Health call, the European Research Council (ERC), the MycoSynVac project under the EU’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation program, the Generalitat de Catalunya, and the Instituto de Salud Carlos III.

The new treatment specifically targets biofilms, colonies of bacterial cells that stick together on a surface. The surfaces of medical implants are ideal growing conditions for biofilms, where they form impenetrable structures that prevent antibiotics or the human immune system from destroying the bacteria embedded within. Biofilm-associated bacteria can be a thousand times more resistant to antibiotics than free-floating bacteria.

Staphylococcus aureus is one of the most common species of biofilm-associated bacteria. S. aureus infections do not respond to conventional antibiotics, requiring patients to surgically remove any infected medical implants. Alternative therapies include the use of antibodies or enzymes, but these are broad-spectrum treatments that are highly toxic for normal tissues and cells, causing undesired side effects.

The authors of the study hypothesized that introducing living organisms that directly produce enzymes in the local vicinity of biofilms is a safer and cheaper way of treating infections. Bacteria are an ideal vector, as they have small genomes that can be modified using simple genetic manipulation.

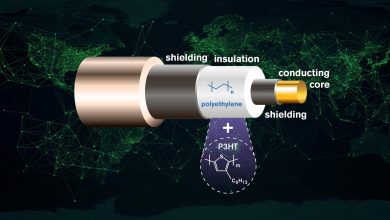

The researchers chose to engineer Mycoplasma pneumoniae, a common species of bacteria that lacks a cell wall, making it easier to release the therapeutic molecules that fight infection while also assisting it in evading detection from the human immune system. Other advantages of using M. pneumoniae as a vector include its low risk of mutating new abilities, and its inability to transfer any of its modified genes to other microbes living nearby.

M. pneumoniae was first modified so that it would not cause illness. Further tweaks made it produce two different enzymes that dissolve biofilms and attacks the cell walls of the bacteria embedded within. The researchers also modified the bacteria so that it secretes antimicrobial enzymes more efficiently.

The researchers first aim to use the modified bacteria to treat biofilms building around breathing tubes, as M. pneumoniae is naturally adapted to the lung. “Our technology, based on synthetic biology and live biotherapeutics, has been designed to meet all safety and efficacy standards for application in the lung, with respiratory diseases being one of the first targets. Our next challenge is to address high-scale production and manufacturing, and we expect to start clinical trials in 2023,” says María Lluch, co-corresponding author of the study and Chief Science Officer of Pulmobiotics.

The modified bacteria may also have long-term applications for other diseases. “Bacteria are ideal vehicles for ‘living medicine’ because they can carry any given therapeutic protein to treat the source of a disease. One of the great benefits of the technology is that once they reach their destination, bacterial vectors offer continuous and localized production of the therapeutic molecule. Like any vehicle, our bacteria can be modified with different payloads that target different diseases, with potentially more applications in the future,” says ICREA Research Professor Luis Serrano, Director of the CRG and co-author of the study.

Reference: “Engineering a genome-reduced bacterium to eliminate Staphylococcus aureus biofilms in vivo” 6 October 2021, Molecular Systems Biology.

DOI: 10.15252/msb.202010145