On the 26th of February 1852, a British troopship, HMS Birkenhead sank off the coast of South Africa while carrying reinforcements. She would never reach her destination.

The bravery and discipline shown by the British soldiers on board, despite their impending doom, would echo down the ages to the modern-day.

The ship sank very quickly, but the men would stay with the ship to keep the lifeboats from being swamped and ensure the survival of the women and children on board. An event still honored today with the tradition of “woman and children first” in times of peril.

What is the origin of “women and children first”?

While most commonly associated with events like the sinking of the Titanic, the origin of this saying actually dates back to the lesser-known tragedy of the HMS Birkenhead.

The events of the ship’s sinking would be immortalized in song and history, and lead to the “Birkenhead Drill” — the informal, yet now standard practice of evacuating women and children first when a ship is sinking.

The story of the sinking is both tragic and inspiring in equal measures and is well worth spending a little time exploring. You may even find yourself shedding a tear.

Let’s take a little trip back in time…

What was the HMS Birkenhead?

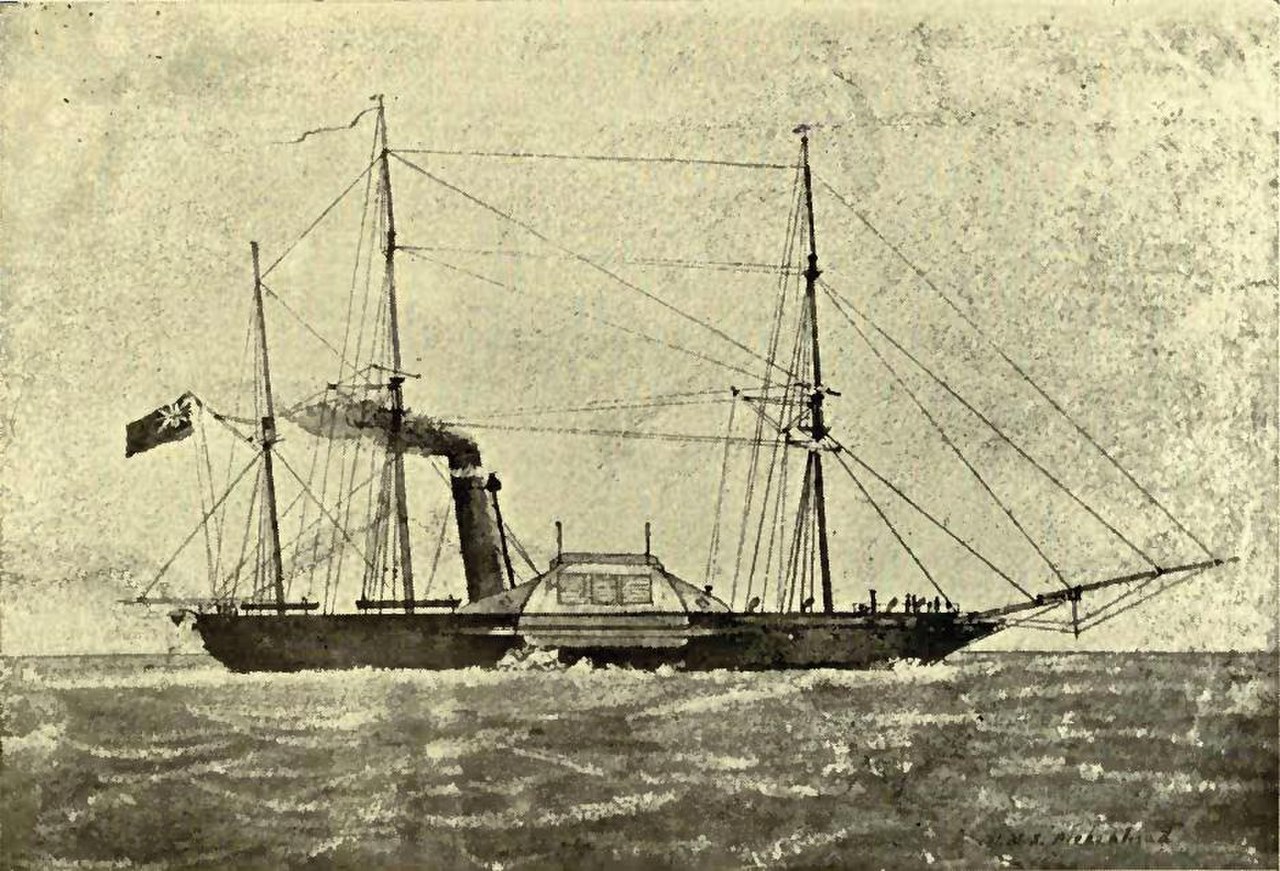

On the 25th of January 1852, the iron-hulled paddle steamer, HMS Birkenhead, set sail from Portsmouth for what was meant to be a routine troop transport mission. First laid down as the naval frigate HMS Vulcan, she was one of the first iron-hulled ships to ever enter the service of the Royal Navy.

Originally designed as a steam frigate, she was later converted into a troopship just prior to being commissioned. She displaced around 1918 tons and was built at the town from which she derived her name. She was one of the first of her kind to be built of iron, which tended to be brittle.

Iron plates, while strong against cannonballs, were prone to tearing. A critical weakness for the events to come.

The Birkenhead was among the early attempts to merge sail and steam. She was rigged like a barquentine, with a third mast. Her main propulsion, however, came from her two Forrester & Co 564 hp (421 kW) steam engines. These turned 20 ft (6 m) diameter paddle wheels on either side of the hull.

Onboard were troops from several different British military regiments including the 74th Regiment of Foot, the Queen’s Royal Regiment, as well as officers’ wives and children. She left Portsmouth in January. Her first port of call was Queenstown (now Cobh) in Ireland, where a fresh regiment boarded the vessel bound for South Africa.

These troops had never seen combat, and many had signed up to evade the hardships of the “potato famine” in Ireland at the time. From Ireland, HMS Birkenhead set sail for South Africa to deposit her cargo of fighting men to assist in the Eighth Cape Frontier War (1850-53).

The voyage from Ireland was a particularly rough one. The ship sailed into a terrible storm immediately on leaving port — a fact which points to the urgency of the voyage.

Many sailing ships of the day would have put back into port in such weather. However, the Birkenhead was in a hurry. She was under orders to get the reinforcements she carried as quickly as possible to South Africa. In fact, her 47-day passage to Simon’s Town, South Africa set a record for the time.

The exact numbers of crew and passengers are hard to estimate, but somewhere in the region of 643 is often quoted. This figure included around 31 children, 25 women, and 125 crew.

This is not unusual for the time, as officers would regularly take their families with them on campaigns such as this. However, the presence of so many women and children onboard would cement the HMS Birkenhead in the history books.

On the 23rd of February, HMS Birkenhead docked at Simon’s Town near modern-day Cape Town to take on food and water, cavalry horses, and feed ready for her final leg. Some women and children and sick soldiers also embarked, but not all. On the 25th of February, the ship embarked on what would be her final voyage.

To ensure the ship made the best speed, the ship’s captain, Captain Salmond, ordered the vessel to hug the South African Coast. To this end, a course was set that kept the ship roughly 3 miles (4.8 km) from the shore.

Using her paddle wheels, she maintained a steady speed of 8.5 knots (15.7 km/h). The sea was calm and the night was clear as she left “False Bay” and headed east.

However, being this close to shore came with the added risk of unforeseen hazards at sea as the water was shallower. While charts were generally pretty good for the area, the calm weather gave the crew, what would turn out to be, a false sense of security.

Lookouts were posted fore and aft, and officers were on station on the bridge and sailors on watch throughout the final leg. Everything seemed to be going to plan. With the exception of the duty watch, everyone else was tucked up asleep in their quarters.

At around 2 am on the morning of the 26th of February, a sailor’s voice broke the night-time silence to announce “12-fathoms, all is well”.

A fathom is roughly 5.9 ft (1.8 m) in depth.

This was the leadsman, a sailor tasked with taking water depth readings. Another sailor announced that they were at “4-bells”, meaning they were halfway through the watch.

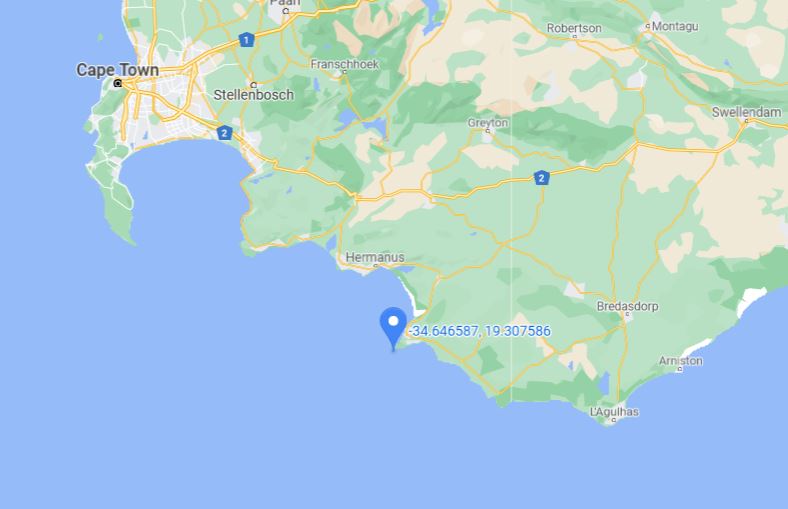

The ship was making good progress. At just that moment, the Birkenhead ran full steam into an unknown, and unseen, hidden reef of rock at a place called “danger point”.

Rocks were noted on the charts in this area, but for whatever reason, this particular one had never been plotted. The rock was roughly 2 fathoms (3.7 m) below the water and was barely submerged in calm seas. If the sea had been a little more turbulent, the crew of the ship would likely have readily seen it.

A case of sheer bad luck.

She hit the rocks so hard that with her paddles continuing to run full speed, that she was dragged even further onto the rocks — fatally wounding the ship. Her hull was torn open from the compartment between the engine room and forepeak.

Water flooded into the forward compartment of the lower troop deck filling it instantly. Hundreds of soldiers were trapped and drowned in their hammocks as they slept. These would be just the first of many casualties that night.

Moments later, the ship’s captain rushed onto the deck and ordered the ship’s anchors to be dropped and for the quarter-boats to be released and lowered into the water. It was time to abandon ship.

How did the Birkenhead sink?

All surviving crew and passengers were ordered to muster on deck and await their officers’ orders. Captain Salmond requested that some of the soldiers help to man the pumps, and sixty were assigned in a vain attempt to raise the rapidly flooding forward section of the Birkenhead.

Soon after, all the women and children were also ordered on deck ASAP. The walking wounded soon began to appear on deck as well.

Another sixty, or so, were tasked with releasing the lifeboats, and the rest ordered to stand at attention on the poop deck of the ship to act as a counterweight at the rear of the vessel. The ship’s cutter, a small coastal patrol vessel, was deployed and the women and children were ordered to board it.

Of the ship’s eight lifeboats (including the cutter), two (with a capacity of 150 each) were crewed, but one was immediately swamped and the other could not be launched due to poor maintenance and dried paint on the winches.

This left only three smaller boats available and these were soon filled with women, children, and some of the ship’s crew.

All other surviving soldiers and officers remained assembled on deck. The senior officer on board, Lieutenant-Colonel Seton of the 74th Foot, took charge of all military personnel. He summoned his officers around him and stressed the importance of maintaining discipline. Seton drew his sword and ordered his men to stand fast.

Noticing the desperation of the situation, Captain Salmond made a fateful decision. He ordered that the Birkenhead reverse course and back off the rock in order so that the remaining lifeboats could be launched. It is this decision that would prove to be the final nail in the coffin for the ship.

The Birkenhead broke free from the rocks, only to be struck once again. Her formidable hull plates, namely round her bilge, were bent and bucked, resulting in internal bulkheads failing. The ship’s fate was now sealed.

At one point the ship’s funnel collapsed over the side and forepart of the ship, killing anyone in its path. The stern section, now crowded with men, floated for a few minutes before sinking.

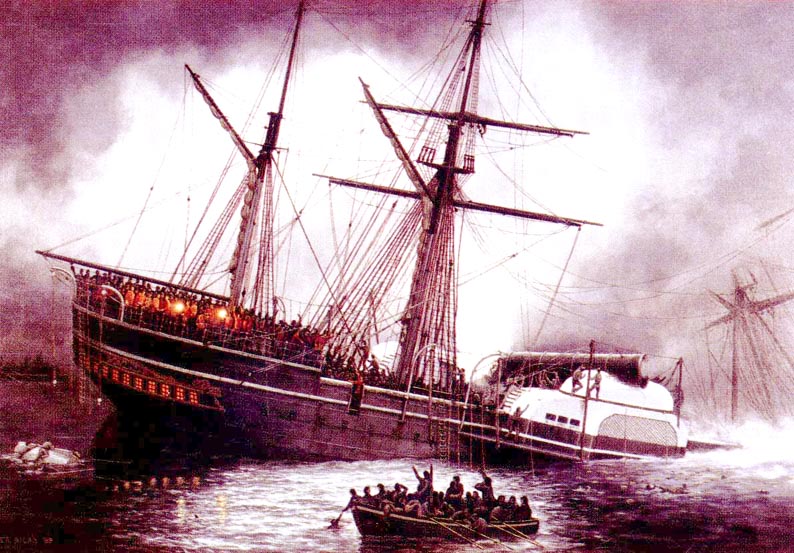

It was at this point that the Birkenhead would go down, literally and figurately, in history. Captain Salmond called out to all survivors “all those who can swim jump overboard, and make for the boats”.

Colonel Seton, realizing the immediate danger of large amounts of panicking men swamping the boats, countermanded the order. “You will swamp the cutter containing the women and children. I implore you not to do this thing and I ask you all to stand fast!”, Seton pleaded to the survivors.

The novice soldiers did not move, even as the ship split apart, and the brave company slipped down into the waves. As a survivor later recounted: “Almost everybody kept silent, indeed nothing was heard, but the kicking of the horses and the orders of Salmond, all given in a clear firm voice.”

Only a handful of soldiers broke ranks and made for the boats, but this was very much the exception. As Captain Edward Wright of the 91st (Argyllshire Highlanders) Regiment would later recall.

“The order and regularity that prevailed on board, from the moment the ship struck till she totally disappeared, far exceeded anything that I had thought could be affected by the best discipline… Everyone did as he was directed and there was not a murmur or cry amongst them until the ship made her final plunge — all received their orders and carried them out as if they were embarking instead of going to the bottom of the sea.”

Cavalry horses were blinkered and released into the water in the hope that they could make it to land. Amazingly, some of them actually made it with one officer finding his horse on land later on that day.

When the ship finally sunk, those soldiers who did not drown remained calm, clinging onto anything that floated. Not one attempted to swim to the lifeboats.

The Birkenhead slipped beneath the waves in less than twenty-five minutes after she had struck the rocks, with only the topmast and sailcloth remaining visible above the water, with about fifty men still clinging to them.

How many people died on the Birkenhead?

The sea was full of men desperate for anything that could float. But they were not out of danger yet. The waters around False Bay, South Africa are home to sharks, many of them.

Great White sharks, mako sharks, tiger sharks, and many other species are very common. This night they would eat their fill.

After circling the survivors for a short while, they gained confidence and then began to feed on the dead and dying, before turning on the other stricken sailors. According to some accounts, the sharks appeared to have a preference for those sailors who were either naked or barely clothed.

This fits with modern research of sharks like the 2010 French film Oceans, which shows footage of humans swimming next to sharks in the ocean. It has been speculated that sharks are able to “sense” unnatural elements like clothing or polyurethane diving suits and air tanks, which may result in sharks treating wearers as curiosities rather than prey. In other words, the bioelectrical signatures of bare skin are masked.

Those spared from the jaws of sharks either drowned or died of exposure. Some did manage to make it the 2 mi (3.2 km) to shore over the next 12 hours.

Witnessing the plight of the soldiers and sailors in the water, the women on board the lifeboats pleaded with the crew to return and help rescue who they could. This they did, but very few of the men in the water would approach the boats.

One young officer, Ensign Alexander Russell, assigned to one of the boats, dived into the water to rescue one of the women’s husbands, and helped him to the boat, where he was given Ensign Russell’s place. Russell would then attempt to make for land but was taken by sharks shortly after.

As the sun rose the same day, the schooner Lioness appeared on the scene and discovered one of the cutters adrift at sea. After which she headed for the scene of the disaster, reaching the wreck that afternoon, and picking up the remaining survivors.

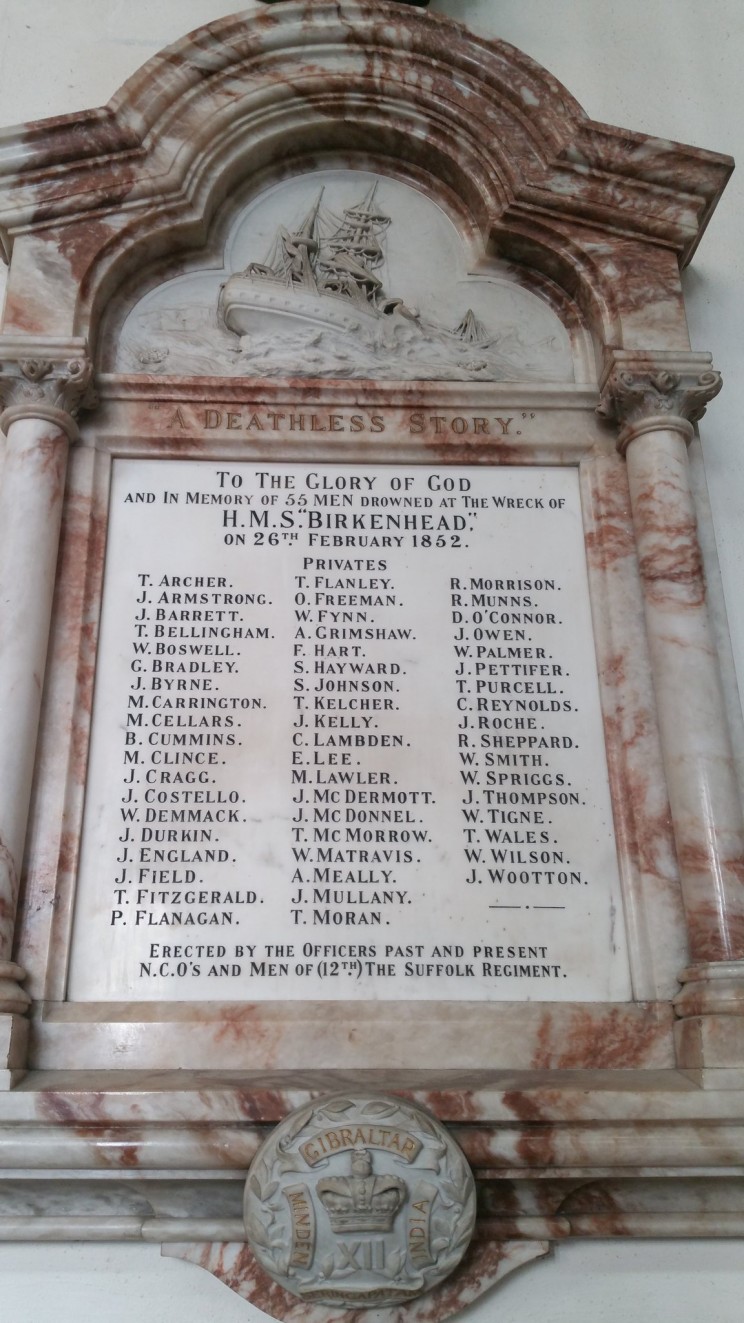

Of the 640, or so, people on board HMS Birkenhead, somewhere in the region of 190 survived. Captain Edward WC Wright of the 91st Argyllshire Regiment was the most senior army officer to survive; he was awarded a brevet for his actions during the ordeal, dated 26 February 1852.

The numbers are very difficult to estimate, however, as the muster rolls and logbooks of the Birkenhead were lost with the ship. However, it is generally now believed that the survivors comprised 113 soldiers (all ranks), 6 Royal Marines, 54 seamen (all ranks), 7 women, 13 children, and at least one male civilian.

The sinking of the Birkenhead was a maritime disaster of the first order. But it also provided a wake-up call on the vital subject of safety at sea. It would also inspire a tradition still honored today.

While the famous words “women and children first” were never spoken that night, the courage and discipline of the soldiers that night would go down in history.

The tragedy of the Birkenhead had repercussions around the world too. King Frederick William IV of Prussia, for example, was so impressed by the bravery and discipline of the soldiers and crew of the Birkenhead, that he ordered an account of it to read at the head of every regiment of his army.

Queen Victoria herself was also deeply moved by accounts of the accident and ordered an official monument to be built at the Chelsea Royal Hospital.

In 1892, Thomas M. M. Hemy painted a widely admired depiction of the incident, “The Wreck of the Birkenhead”. Prints of this painting were distributed to the public and were very popular at the time.

Around about the same time, a lighthouse was erected at Danger Point to help warn other ships of the potential hidden dangers of the area. Standing at around 59 ft (18 meters) tall, the lighthouse is visible for approximately 25 nautical miles (46 km).

In the 1930s, a remembrance plate to the loss of the Birkenhead was affixed to its base by the Navy League of South Africa. A new Birkenhead memorial was erected nearby in March 1995. In December 2001, the plaque was moved closer to the lighthouse.

In 1977, the South African mint issued a “Heroes of the Birkenhead Medallion” gold coin commemorating the 125 years since the sinking, featuring Hemy’s painting on one of the faces of the coin.

Who was to blame for the accident?

Following the incident, an official investigation was undertaken by the British government. Several surviving sailors were even court-martialed.

The court-martial was held on board HMS Victory in May of 1852 and attracted a lot of public attention at the time. None of the sailors on trial were senior officers of the ship and, as such, none of them were convicted of any wrongdoing.

But who, if anyone, was to blame for the accident?

This has been mulled over by many in the intervening years, but since we only have historical accounts from survivors recording the events of that night, it is almost impossible to attribute blame to anyone. From what we can ascertain, the initial impact was simply a case of bad luck. The charts for the area did not record the reef, and it could not be seen when the sea is calm.

However, the actions after the impact were at the sole discretion of the captain and his other senior officers. Why did Captain Salmond travel in such shallow waters? Was the decision to back off from the reef really necessary?

The first question can be answered fairly easily. Captain Salmond, whose family had served in the Royal Navy since the reign of Queen Elizabeth 1, had been given explicit orders to get the Birkenhead and all onboard to Algoa Bay as quickly as possible.

To meet this demand from his superiors, the captain took a calculated risk of hugging the coastline. As an experienced captain, and the fact that charts did not record the presence of the rock, the initial impact can not really be blamed on Captain Salmond.

The events after the impact, however, are, ultimately, the responsibility of the captain. However, his actions appear to have been in the best interests of saving the survivors of the accident.

We can never know for sure if the ship would have stayed afloat a little longer if this decision had not been made. Ultimately, however, the main issue was the poor maintenance of lifeboats on board.

Who knows how many more lives could have been saved if the other remaining lifeboats could have been deployed? But hindsight is, as they say, 20:20.

So, next time you hear the call to save the “women and children first” in a film or TV drama, spare a moment to think of the brave men who inspired it.