Lead Image: The world’s first manned space rocket at an exhibition in Moscow city, Russia. Image Credit: Armastas/iStock

In the mid-1970s, the Soviet Union became the first, and to date, only nation, to have actually fired a cannon in space. Mounted on a space station, the actual details of the endeavor have remained secret for over forty years until now.

Let’s take a look at this historic event.

Did the Soviets really install a working cannon on a space station?

In short, yes they did. Called the R-23M, the cannon was installed and tested on the Almaz space station in the 1970s.

Derived from a very powerful revolver-like aircraft weapon, the gun is the only one officially known to have actually been successfully fired in space.

Based on a Cold War-era bomber tail gun cannon, the weapon has remained the subject of much speculation until official records were released a few years ago.

According to these records, the weapon’s development was tasked to the Moscow-based KB Tochmash Design Bureau. They quickly assigned their chief engineer in such matters, Aleksandr Nudelman, to also lead the project.

This was the obvious choice for the Soviet Union, as KB Tochmash had made a name for themselves with many technological breakthroughs in aviation weaponry since the Second World War.

The team, after some deliberation, developed a 37/64ths of an inch (14.5-mm) rapid-fire cannon that could, allegedly, hit targets as far as two miles (3.2 km) away. Opinions do vary, but the weapon is said to have been able to fire from 950 to 5,000 shots per minute, launching 200-gram shells at a velocity of 690 meters per second (1,500 miles per hour).

For a space-based weapon, that is more than enough of a punch to make a huge difference. But, firing such a weapon in space has many more variables and potential problems than on Earth.

For example, while such a cannon could be used in a similar fashion to on Earth, i.e., using an optical sight from the cockpit, this did not guarantee a hit. Unless the target was generous enough to approach within your field of fire, you’d need to potentially move the entire spacecraft to center in on the target.

But, according to “Almaz” project veterans, this is exactly the kind of thing that was achieved. They were able to actually pierce a metal gasoline canister target from a mile away (1.6km) during its ground tests.

It would take until the fall of the Soviet Union for further information to come to light about the real extent of the weapon, however. According to these sources, the Soviet Union actually managed to fire the weapon on the 24th of January, 1975, from the Salyut-3 space station (more on the station later).

As this was a completely unprecedented event, officials behind the project could not be entirely sure how it might impact the integrity of the space station. So, the test-firing was scheduled only hours before the official de-orbiting of the station itself.

It also occurred after the crew on board had been returned to Earth a few months beforehand.

To conduct the test, the jet thrusters on the station were ignited at the same time as the cannon was fired. This was to counteract, as best they could, the recoil of the gun, which was very powerful. This is especially the case in near zero-g.

According to various sources, the cannon fired from one to three blasts, reportedly firing around 20 shells in all. All shells reportedly burned up in the Earth’s atmosphere.

While the actual results of the test are still classified, it does appear that the later Soviet armed space stations were to be outfitted with missiles rather than projectile weapons. We’ll let you conclude why this might have been the case.

In any case, no further armed space stations would be completed by the Soviet Union, with the last armed “Almaz” being permanently mothballed in 1978.

Since then, a few scraps of information have come to light about the project, including a rare photo of the R-23M cannon. However, the validity of this photograph has been put into question, as it appears to be an aircraft-mounted variant rather than the one sent to space.

Back in 2016, however, some very grainy footage of what is supposed to be the space cannon was aired on Voennaya Priemka, a military show produced by the Zvezda TV channel associated with the Russian Ministry of Defense.

The episode in question included footage from the inside of the limited-access corporate museum at KB Tochmash. This footage provided a 360-degree view around the cannon for all to see.

What do we know about the space cannon itself?

According to available records and information, the gun was a variant of the Soviet Rickter R-23. This was an aircraft autocannon developed by the Soviet Union for use on Soviet aircraft in the late 1950s.

Designed to have a short barrel, it was specifically designed to overcome issues with pointing guns into the airstream of high-speed jet aircraft. This weapon was a gas-operated, revolver-type cannon that would recycle bled gas from holes in the barrel to assist with the motive force.

The cannon weighed roughly 129lbs (58.5kg), had a length of 4ft and 10-inches (1.468m), and was 90 caliber, or 0.9-inch (23mm). It also had a muzzle velocity of 2,800 feet-per-second (850 m/s).

It could fire around 2,000 rounds per minute and was the fasted firing single-barrel cannon ever introduced into service. Given the technical difficulties of such a weapon, it took some time to fully develop and was not made operational until the mid-1960s.

The cannon was primarily used as the primary armament for the tail defensive turrets of the Russian Tupolev Tu-22 jet strategic jet bomber.

What space station was the Soviet space cannon fired from?

As previously mentioned, the RM-23 cannon was mounted on the Salyut-3 (aka “Almaz” OPS-2) space station. Launched in 1974, this was the second military laboratory for the Soviet Union put into orbit, but was officially part of the “civilian” Salyut series.

On the 25th of June 1974, the OPS-2 space station, after some technical difficulties throughout the night, finally launched from the “left hand” launch pad at Site 81 in Baikonur. Officially equipped with “electro-mechanical” altitude control systems (aka gyrodines), rotating solar arrays, is an “improved” thermal control system, it also featured separate areas for work and rest. Salyut-3 was ready for its top-secret missions months later.

The space station also had water-recycling facilities and an unmanned reentry capsule.

According to official records, the official payload for OPS-2 included but was not limited to:

- An Agat-1 photo camera that had a focal length of 6,375 millimeters and a resolution greater than 3 meters

- An OD-5 optical visor

- A POU panoramic device

- A topographical camera

- A star camera

- A Volga infrared camera with a resolution of 100 meters

The space station had around 14 cameras in total, according to Cosmonaut Pavel Popovich, who would man the station before it was officially deorbited.

Throughout the station’s relatively short lifespan, it received two crewed missions, Soyuz-14 and Soyuz–15. The former occurred in early July of 1974, with crew members spending 15 days onboard.

During this time, the station’s “remote-sensing equipment” was activated and used to photograph large parts of the Earth’s surface. Other than that, the crew conducted various system checks and other housekeeping duties.

They also reloaded the station’s onboard camera films.

The latter mission occurred in late August of 1974. While officially sent to “[test] various rendezvous modes during its mission,” it has since been revealed that the crew faced some very serious problems when trying to dock.

When Soyuz-15 reached a distance of around 300-meters from the station, the Igla (“needle”) rendezvous system failed to switch to final-approach mode. Instead, it triggered a sequence of commands that would normally be used kilometers out from the docking point.

This meant that Soyuz-15, and its crew, were launched toward the station, using thrusters, at around 72 kilometers per hour. Thankfully for all concerned Soyuz-15 missed a direct impact and overshot the station by about 40 meters.

As the crew failed to realize the problem (and shut down the Igla), the rendezvous system attempted to re-acquire radio contact with the target and sent the Soyuz-15 to the station two more times, again narrowly avoiding a deadly collision. By the time ground control ordered the deactivation of the Igla, the crew only had enough propellant for the descent back to Earth and the mission was aborted.

Following an investigation into the potentially disastrous events of the Soyuz-15 mission, the required modifications needed to safely dock further missions to the station were deemed untenable and the station was then scheduled for destruction.

Salyut-3 spent a total of seven months in orbit, which while short, actually exceeded initial expectations for the space station.

Throughout its short life, Salyut-3, beyond carrying the first operational space weapon, also made some other firsts in space history. For example, it was the first to maintain a constant orientation to the Earth’s surface.

This was achieved through firing its attitude control thrusters no less than half a million times.

Why did the Soviets put a working cannon in space?

At the height of the Cold War, the Soviet Union were obsessed with the possibility that American spacecraft were becoming increasingly sophisticated in their capability to approach and monitor Soviet military space assets. Since the Soviet Union was naturally very protective of its own secrecy, this situation, if true, was unacceptable.

This is especially the case as these military space assets did not officially exist – at least according to official Soviet propaganda.

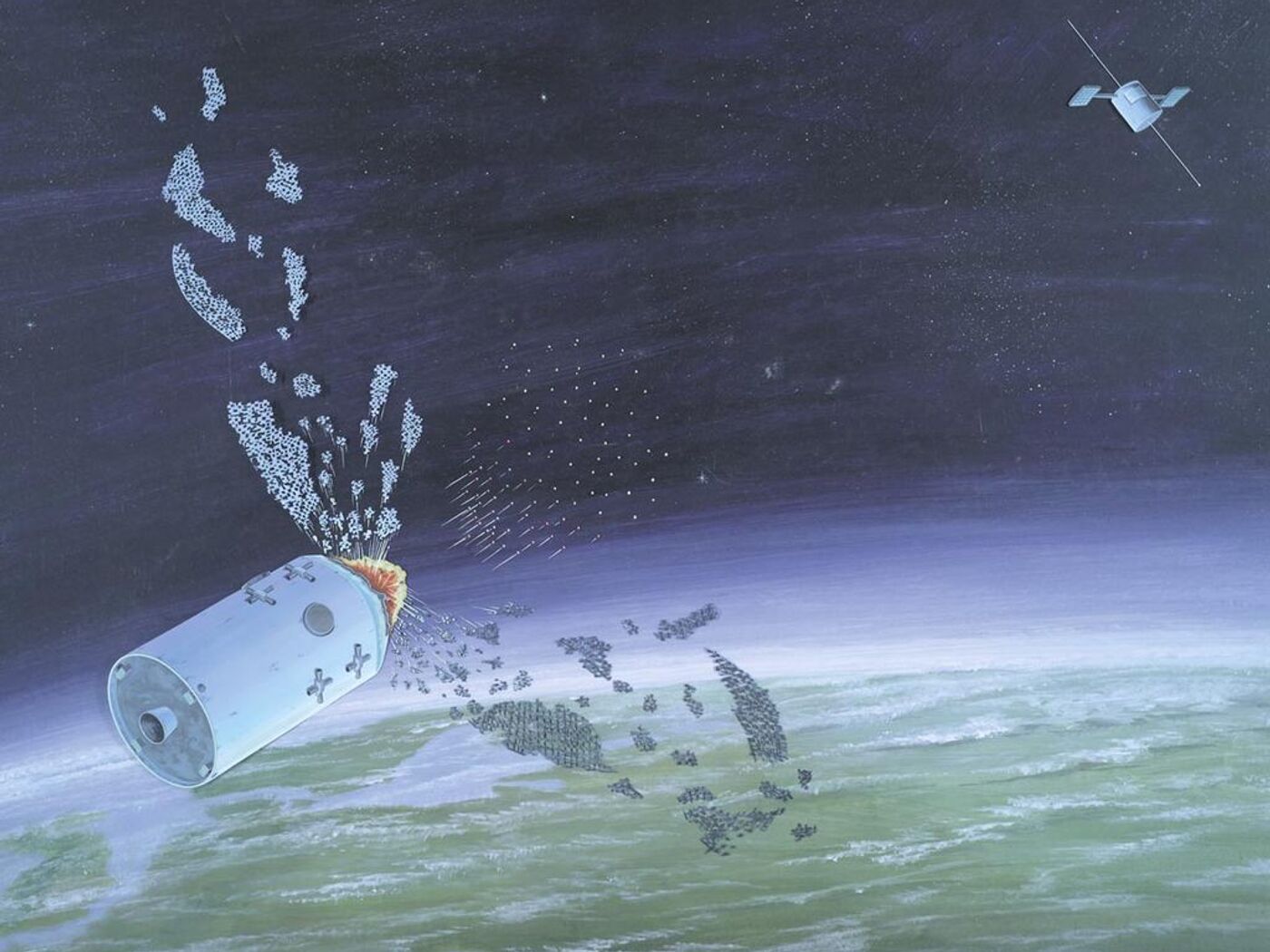

This was not, as it turns out, completely unhinged, as both NATO (primarily America), and the Soviet Union were developing anti-satellite technologies and an incredible pace. For this reason, it was a perfectly logical step to mull over methods of enabling spacecraft to have some form of self-defense, like actual kinetic weapons.

At the same time, the Soviet Union had developed its first space station project, code-named Almaz (meaning “diamond”). This was an obvious asset to fortify against potential belligerent interests. “Almaz” was a habitable space outpost and was initially developed exclusively for military purposes, primarily reconnaissance.

It was the obvious choice to test out some potential defensive weapons.

While the gun itself had been in development since around the mid-1960s, the actual space station that would accommodate it was facing some serious delays. For example, its planned package of high-tech payloads and sensors was rapidly falling behind schedule.

These delays aside, the focus of the Soviet military was shifting to the use of unmanned satellites to provide a similar function as well. Worst still for the project, the United States was scheduled to complete and deploy its Skylab space station in 1973.

This would mean that the Soviet Union would face losing the race to become the first nation to deploy a space station in orbit. To this end, efforts were redoubled to get the project complete first.

Instead of the original, more ambitious, space station, a smaller civilian outpost was assembled out of off-the-shelf parts from the existing Soyuz spacecraft and completed “Almaz” gear. The finished craft, an orbital laboratory, was then successfully launched in 1971 and christened “Salyut”.

This achievement had an instant impact on public opinion, which helped boost the Kremlin’s support for the “Almaz project”. With the race to put the first space station in orbit, the pressure was off a little and there was time to fully flesh out the more sophisticated Almaz station.

By 1982, the Soviet Union managed to deploy around seven space stations in orbit, all under the name of “Salyut.” Three of these, however, were actually spy stations for “Almaz”.

The Western intelligence and independent observers soon figured out which was which, but the “Almaz” program officially remained under wraps until the end of the Cold War.

And that’s your lot for today.

While many details about Salyut-3 and its infamous space cannon are still very much not public knowledge, there is no doubt that this was one of the most significant events in space exploration history. Who knows how many other military spacecraft orbiting Earth were similarly armed in the past, or indeed today.

Since such projects would be concealed by the thickest of national security protections, we will likely never know.