The Andromeda Galaxy is the second most famous galaxy in astronomy, after our home galaxy, the Milky Way. It’s our galactic neighbor and among the easiest to see in the night sky, but for centuries, most astronomers had no idea what it was.

Fortunately, we know a lot about the Andromeda Galaxy now, and it has become an object of endless fascination in both astronomy and popular culture.

But how did we go about discovering it in the first place? How were we able to tell it was a galaxy like our own? Will we ever be able to visit it one day, and do we know if Andromeda can support life?

What is the Andromeda Galaxy?

The Andromeda Galaxy is a barred spiral galaxy about 2.48 million light-years away from Earth, located in the constellation Andromeda. It is officially designated Messier 31 (M31), or NGC 224, and records of its observation in the night sky date back to many centuries.

Since its apparent magnitude is 3.4, it is visible to the naked eye on a clear and dark night, so it isn’t possible to say who “discovered” it, though the earliest known record of it appears in 964 CE in the Book of the Fixed Stars by the Persian astronomer Abd al-Rahman al-Sufi.

The American astronomer Edwin Hubble was the first person to have conclusively demonstrated that Andromeda was a separate galaxy apart from our own in 1925, and not a nebula as previously believed.

The Andromeda Galaxy is also of particular importance to astronomers since it bears a lot of similarities to our own galaxy, and is the most distant object in the universe that is visible to the naked eye.

Is the Andromeda a Galaxy or is Andromeda a Nebula?

Andromeda is our largest and nearest galactic neighbor, and for centuries, it was believed to be a nebula of little significance. French astronomer Charles Messier cataloged the “Andromeda Nebula” in 1774 as Messier 31 (M31) — the 31st item in his catalog of “objects to avoid” when comet-hunting.

Originally, Messier wasn’t particularly interested in the objects he was cataloging in themselves. As an avid comet hunter, Messier compiled his catalog of objects that could be easily mistaken for comets to help prevent false-positive comet identifications.

Still, the prominence of M31 made it an object of particular fascination for astronomers, including British astronomer William Herschel, who thought it was the closest of the “great nebulae” in the universe.

The Andromeda Nebula factored into the Great Debate between astronomers Heber D. Curtis and Harlow Shapley in 1920 about the scale of the universe.

Curtis argued that spiral nebulae like the Andromeda Nebula were actually separate galaxies and that the Milky Way was just one galaxy among many. Shapley disagreed, arguing that the nebulae were just spiral pockets of gas and that there were no galaxies, just the universe (which was essentially just the Milky Way).

The debate concluded without a decisive winner, but half a decade later, Edwin Hubble would use data from a special class of stars in the Andromeda Nebula to put its distance from us nearly a million light-years away, much farther away than the furthest identifiable star in the Milky Way. This pretty much put the galaxy question to rest.

Facts about the Andromeda Galaxy

Weighing between one and two trillion solar masses, the Andromeda Galaxy is thought to be about 10 billion years old and is likely the product of the merger of several smaller protogalaxies.

It has long been thought that Andromeda was substantially larger than the Milky Way in terms of mass, but recent research has somewhat downgraded the Andromeda Galaxy’s mass while increasing the mass of our own galaxy. Now, the masses of the two galaxies are thought to be much closer than previously believed.

What isn’t in dispute is its physical dimensions, which stretch farther than our own galaxy with a diameter of about 220,000 light-years, compared to the roughly 100,000 to 175,000 light-year diameter of the Milky Way.

Not only is Andromeda physically bigger than the Milky Way, but it is also the largest galaxy in the Local Group by dimensions, if not by mass.

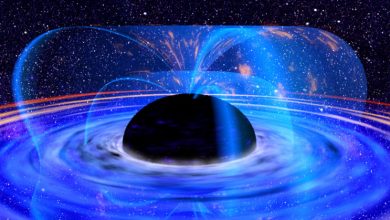

The Andromeda Galaxy is known to have a very active galactic nucleus, with a dense cluster of stars near its center. When imaged by Hubble, the galactic core appears to show two points of concentration, with a brighter concentration just off the true galactic center, which is the second point of concentration.

This second point is home to a supermassive black hole most recently measured at 1.1–2.3 × 108 solar masses (or 110 to 230 million suns). It is thought that the brighter point of concentration is a result of stars bunching up at the perihelion of their elliptical orbits around the central black hole.

There are thought to be about 460 globular clusters in the Andromeda Galaxy, indicating that it has been an active devourer of smaller galaxies, and so is considered typical for a spiral galaxy.

It is also believed that the Andromeda Galaxy is transitioning from a spiral galaxy to a fairly rare type of galaxy known as a ring galaxy. This can be deduced from “hidden” overlapping arms that appear in infrared light to reveal a ring structure around the galactic nucleus.

How many stars are there in the Andromeda Galaxy?

The Andromeda Galaxy is thought to have about 1 trillion stars, by far the most of any galaxy in the Local Group.

This is likely due mostly to Andromeda’s interaction with and absorption of smaller galaxies over the last few billion years.

The age of the Andromeda Galaxy along with observational data indicates that the rate of star formation in Andromeda is on the decline as it has used up most of its native interstellar hydrogen gas.

This means that the number of new stars in the Andromeda Galaxy will eventually be overtaken by stellar corpses and slow-burning red dwarfs, pushing it into the red galaxy category.

Can the Andromeda Galaxy support life?

Since we can’t yet say for certain whether there are any other stars in our own galaxy that host life, it is even harder to say whether there might be life, or at least the conditions for life, in another galaxy.

Still, the Andromeda Galaxy is a lot like our own galaxy, and we know of at least one star in the Milky Way that is able to support life as we know it.

The Milky Way has between 100 and 400 billion stars in it, so statistically, it’s a pretty good bet that out of the trillion or so stars in the Andromeda Galaxy, there should be up to a dozen or so stars with planets around them that are capable of sustaining life.

Will the Andromeda Galaxy collide with the Milky Way?

The current thinking is that the Andromeda Galaxy is on a collision course with the Milky Way. Before you concern yourself with the consequences of that collision, it should be stated that we will be long gone by then, at least as a species living on planet Earth.

It is expected that the two galaxies will merge to form a new supergalaxy, colloquially known as either Milkomeda or Milkdromeda, depending on which name rolls off the tongue easier.

Before you worry about the consequences for humans in the collision, know that you really shouldn’t, because the collision is expected to start in about 4 billion years and the total merger process will take another two billion years. So, if our sun hasn’t ballooned up into a red giant yet and devoured the Earth (or at least roasted it into complete sterility) by the time the process starts, it certainly will by the time the merger is complete.

If some descendant species of humans is around in 4 to 6 billion years to experience all this, they will be further removed from us than we are from the very first single-celled archaea that formed in the primordial soup of the early Earth.

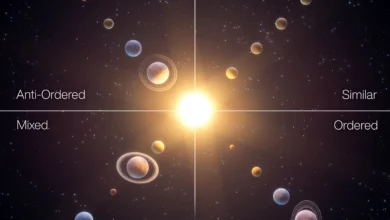

There is a chance that our solar system could be ejected into the intergalactic medium in the process, but that’s impossible to know with any certainty, as is the structure the new galaxy will take as a result of the collision.

It is likely, though, that the galactic disks of both galaxies will be disrupted and the spiral arms (or rings) of the two galaxies will be dispersed. Whether that will lead to Milkomeda becoming an elliptical galaxy or a large disk galaxy can’t be known with any certainty.

Differences between the Milky Way and the Andromeda Galaxy

While we’ve been talking a lot about the similarities between the Andromeda Galaxy and the Milky Way, there are some pretty big differences.

First, Andromeda has way more stars than the Milky Way, possibly ten times as many. Though it might have more stars, it’s not nearly as active, producing an estimated one new solar mass of stars a year, compared to the Milky Way’s three to five solar masses a year.

The exact age of the Milky Way isn’t known, but there are parts of the Milky Way that are suspected of being at least 13 billion years old. So, the Milky Way may have started forming much earlier than Andromeda.

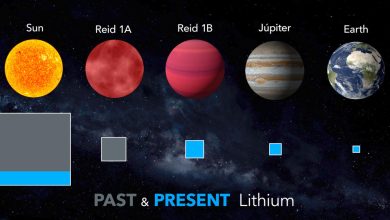

The other major difference is the supermassive black hole in the center of each galaxy. Andromeda’s supermassive black hole absolutely dwarfs Sagittarius A*, the supermassive black hole at the center of the Milky Way.

The Andromeda Galaxy’s supermassive black hole is 1.1-2.3 x 108 solar masses, while Sagittarius A* is about 4.5 x106 solar masses. In other words, the Andromeda Galaxy’s supermassive black hole is about 200,000,000 solar masses heavier.

How to find the Andromeda Galaxy in the night sky

If you want to see the Andromeda Galaxy for yourself, you’re in luck. It is bright enough that you can see it with the unaided eye on a particularly dark night in areas with low light pollution, but it will be easiest with binoculars or a good telescope.

In mid-northern latitudes, the Andromeda Galaxy is visible throughout the year, though some times are better than others. Your best bet is to look around August through October when the galaxy is high up in the sky.

Above -40 latitude in the southern hemisphere, the Andromeda Galaxy is visible in November. Below -40 latitude, however, it is below the horizon at all times, so it can’t be seen.

If you need help finding it, look for the constellation Cassiopeia, which is the W- or M-shaped constellation of five stars. The first peak in the M (or the second valley of the W) can be used as an arrow of sorts that points right at the Andromeda Galaxy, which will be between the constellations Cassiopeia and Andromeda.

What you’re looking for is a bright smudge of light across the sky about the length of a full moon. The easiest way to see it is to first look for it with your eyes, and then once you’ve spotted it, bring a pair of binoculars to your eyes without taking your eyes off the galaxy.

Finding it with a telescope will obviously take a bit more work, but it is undoubtedly worth the effort, as the Andromeda Galaxy remains one of the most spectacular sights in the night sky, however you are able to see it.