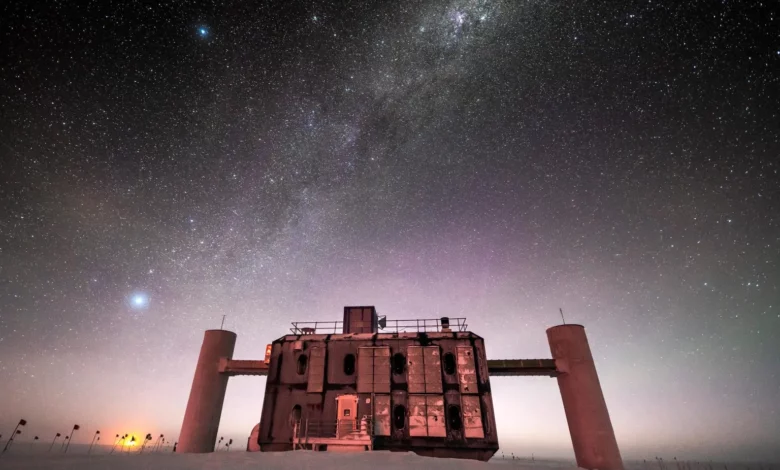

The IceCube Lab sits atop a 1-billion-ton network of sensing equipment and ice at the South Pole. Using the powerful neutrino telescope, researchers have identified a new source of astrophysical neutrinos coming from the galaxy NGC 1068. Credit: Martin Wolf, IceCube/NSF

On Earth, trillions of subatomic particles called neutrinos stream through our bodies every second, but we never notice because they rarely interact with matter. In fact, because they so rarely interact with other matter, neutrinos can travel straight paths over vast distances unimpeded, carrying information about their cosmic origins.

Although most of these aptly named “ghost” particles detected on Earth originate from the Sun or our own atmosphere, some neutrinos come from the cosmos, far beyond our galaxy. Called astrophysical neutrinos, these neutrinos can provide valuable insight into some of the most powerful objects in the universe.

An international team of scientists has, for the first time, found evidence of high-energy astrophysical neutrinos emanating from the galaxy NGC 1068 in the constellation Cetus.

“The IceCube Neutrino Observatory’s identification of a neighboring galaxy as a cosmic source of neutrinos is just the beginning of this new and exciting field that promises insights into the undiscovered power of massive black holes and other fundamental properties of the universe.” — Denise Caldwell, director of NSF’s Physics Division

The detection was made by the IceCube Neutrino Observatory. This 1-billion-ton neutrino telescope is made of scientific instruments and ice that is situated 1.5-2.5 kilometers (0.9 to 1.2 miles) below the surface at the South Pole. The National Science Foundation (NSF) provided the primary funding for the IceCube Neutrino Observatory, and the University of Wisconsin–Madison is the lead institution, responsible for the maintenance and operations of the detector.

These new results, which were published this month in the journal Science, were shared in a presentation given at the Wisconsin Institute for Discovery.

“One neutrino can single out a source. But only an observation with multiple neutrinos will reveal the obscured core of the most energetic cosmic objects,” says Francis Halzen, a University of Wisconsin–Madison professor of physics and principal investigator of the IceCube project. “IceCube has accumulated some 80 neutrinos of teraelectronvolt energy from NGC 1068, which are not yet enough to answer all our questions, but they definitely are the next big step toward the realization of neutrino astronomy.”

IceCube is run by the international IceCube Collaboration, which comprises over 350 scientists from 58 institutions around the world. The Wisconsin IceCube Particle Astrophysics Center (WIPAC), a research center at UW–Madison, is the lead institution for the IceCube project.

WIPAC is responsible for the maintenance and operation of the IceCube Neutrino Observatory, which includes ensuring that the detector runs around the clock. The observatory detects neutrinos through tiny flashes of blue light, called Cherenkov light, which are produced when neutrinos interact with molecules in the ice.

At WIPAC, a diverse team of scientists and technical and support staff make the data science-ready, enabling a wide range of investigations to be carried out by IceCube scientists. The WIPAC team delivered a new version of the first decade of IceCube data that used a significantly improved detector calibration. This superior dataset contributed to the identification of NGC 1068 as a neutrino source.

“Several years ago, NSF initiated an ambitious project to expand our understanding of the universe by combining established capabilities in optical and radio astronomy with new abilities to detect and measure phenomena like neutrinos and gravitational waves,” says Denise Caldwell, director of NSF’s Physics Division. “The IceCube Neutrino Observatory’s identification of a neighboring galaxy as a cosmic source of neutrinos is just the beginning of this new and exciting field that promises insights into the undiscovered power of massive black holes and other fundamental properties of the universe.”

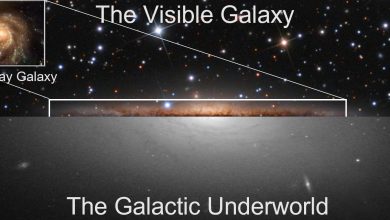

The galaxy NGC 1068, also known as Messier 77, is one of the most familiar and well-studied galaxies to date. Located 47 million light-years away — close in astronomical terms — this galaxy can be observed with a pair of large binoculars.

This video illustrates how IceCube neutrinos have given us a first glimpse into the inner depths of the active galaxy, NGC 1068. Credit: Video by Diogo da Cruz, with sound by Fallon Mayanja and voice by Georgia Kaw

As is the case with our home galaxy, the Milky Way, NGC 1068 is a barred spiral galaxy, with loosely wound arms and a relatively small central bulge. However, unlike the Milky Way, NGC 1068 is an active galaxy where most radiation is not produced by stars, but rather by material falling into a black hole millions of times more massive than our Sun and even more massive than the inactive black hole at the center of the Milky Way.

The excess of about 80 neutrinos detected from the direction of NGC 1068 were found after improving analysis techniques and reprocessing data — work led by IceCube researchers at WIPAC. The revealing neutrino interactions seen in IceCube were modeled using new computational techniques that allow better measurement of each neutrino’s incoming direction, as well as machine learning for a more accurate measurement of the neutrino energy.

This latest result is a significant improvement from a prior study of NGC 1068 published in 2020, according to Ignacio Taboada, a physics professor at the Georgia Institute of Technology and spokesperson for the IceCube Collaboration.

“Part of this improvement came from enhanced techniques and part from a careful update of the detector calibration,” says Taboada. “Work by the detector operations and calibrations teams enabled better neutrino directional reconstructions to precisely pinpoint NGC 1068 and enable this observation.”

Albrecht Karle, a UW–Madison physics professor who is leading efforts to upgrade the current IceCube observatory, says the NGC 1068 detections are “great news” for the future of neutrino astronomy.

“It means that with a new generation of more sensitive detectors there will be much to discover,” says Karle, who is also leading the development of a next-generation neutrino observatory to be built as an extension and technological upgrade of the existing facility at the South Pole.

“The future second-generation IceCube-Gen2 observatory could not only detect many more of these extreme particle accelerators but would also allow their study at even higher energies,” says Karle.

The detection of dozens of neutrinos emanating from NGC 1068 comes several years after IceCube scientists reported the first observation of a high-energy astrophysical neutrino source. That source was TXS 0506+056, a blazar located about 4 billion light-years away, beyond the left shoulder of the Orion constellation. The NGC 1068 observations suggest there are more sources of astrophysical neutrinos yet to be discovered.

“IceCube has previously discovered that the universe is glowing brightly in neutrinos, and the origin of that glow has been an exciting mystery,” says Justin Vandenbroucke, a physics professor at UW–Madison and a member of IceCube. “NGC 1068 provides one key piece of that puzzle and can explain only about one-hundredth of the total signal: There must be many additional neutrino sources, and likely additional types of sources, waiting to be discovered.”

The unveiling of the obscured universe has just started, and neutrinos are set to lead a new era of discovery in astronomy.

Reference: “Evidence for neutrino emission from the nearby active galaxy NGC 1068” by IceCube Collaboration, R. Abbasi, M. Ackermann, J. Adams, J. A. Aguilar, M. Ahlers, M. Ahrens, J. M. Alameddine, C. Alispach, A. A. Alves, N. M. Amin, K. Andeen, T. Anderson, G. Anton, C. Argüelles, Y. Ashida, S. Axani, X. Bai, A. Balagopal V., A. Barbano, S. W. Barwick, B. Bastian, V. Basu, S. Baur, R. Bay, J. J. Beatty, K.-H. Becker, J. Becker Tjus, C. Bellenghi, S. BenZvi, D. Berley, E. Bernardini, D. Z. Besson, G. Binder, D. Bindig, E. Blaufuss, S. Blot, M. Boddenberg, F. Bontempo, J. Borowka, S. Böser, O. Botner, J. Böttcher, E. Bourbeau, F. Bradascio, J. Braun, B. Brinson, S. Bron, J. Brostean-Kaiser, S. Browne, A. Burgman, R. T. Burley, R. S. Busse, M. A. Campana, E. G. Carnie-Bronca, C. Chen, Z. Chen, D. Chirkin, K. Choi, B. A. Clark, K. Clark, L. Classen, A. Coleman, G. H. Collin, J. M. Conrad, P. Coppin, P. Correa, D. F. Cowen, R. Cross, C. Dappen, P. Dave, C. De Clercq, J. J. DeLaunay, D. Delgado López, H. Dembinski, K. Deoskar, A. Desai, P. Desiati, K. D. de Vries, G. de Wasseige, M. de With, T. DeYoung, A. Diaz, J. C. Díaz-Vélez, M. Dittmer, H. Dujmovic, M. Dunkman, M. A. DuVernois, E. Dvorak, T. Ehrhardt, P. Eller, R. Engel, H. Erpenbeck, J. Evans, P. A. Evenson, K. L. Fan, A. R. Fazely, A. Fedynitch, N. Feigl, S. Fiedlschuster, A. T. Fienberg, K. Filimonov, C. Finley, L. Fischer, D. Fox, A. Franckowiak, E. Friedman, A. Fritz, P. Fürst, T. K. Gaisser, J. Gallagher, E. Ganster, A. Garcia, S. Garrappa, L. Gerhardt, A. Ghadimi, C. Glaser, T. Glauch, T. Glüsenkamp, A. Goldschmidt, J. G. Gonzalez, S. Goswami, D. Grant, T. Grégoire, S. Griswold, C. Günther, P. Gutjahr, C. Haack, A. Hallgren, R. Halliday, L. Halve, F. Halzen, M. Ha Minh, K. Hanson, J. Hardin, A. A. Harnisch, A. Haungs, D. Hebecker, K. Helbing, F. Henningsen, E. C. Hettinger, S. Hickford, J. Hignight, C. Hill, G. C. Hill, K. D. Hoffman, R. Hoffmann, B. Hokanson-Fasig, K. Hoshina, F. Huang, M. Huber, T. Huber, K. Hultqvist, M. Hünnefeld, R. Hussain, K. Hymon, S. In, N. Iovine, A. Ishihara, M. Jansson, G. S. Japaridze, M. Jeong, M. Jin, B. J. P. Jones, … J. P. Yanez, S. Yoshida, S. Yu, T. Yuan, Z. Zhang, P. Zhelnin, 3 November 2022, Science.

DOI: 10.1126/science.abg3395

The IceCube Neutrino Observatory is funded and operated primarily through an award from the National Science Foundation to the University of Wisconsin–Madison (OPP-2042807 and PHY-1913607). The IceCube Collaboration, with over 350 scientists in 58 institutions from around the world, runs an extensive scientific program that has established the foundations of neutrino astronomy. Learn more about IceCube’s collaborating institutions on UW–Madison’s website.