Lead image: NASA’s James Webb Space Telescope. Credit: NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center Conceptual Image Lab

Researchers will observe more than a dozen protoplanetary systems to gather data about their inner disks – where Earth-like planets may be forming

What was our Solar System like as it was forming billions of years ago? Over time, particles bumped into one another, building ever-larger rocks. Eventually, these rocks got big enough to form planets. We have some basic understanding of planet formation, but we don’t know the details – especially details about the solar system’s early chemical composition, and how it may have changed with time. And how did water make its way to Earth? While we can’t time travel to get the answers, we can detail how other planetary systems are forming right now – and learn quite a lot. Researchers will train one of Webb’s powerful instruments on the inner regions of 17 bright, actively forming planetary systems to begin to build an inventory of their contents. Element by element, they – along with researchers around the world – will be able to uncover what’s present and how the disks’ chemical makeup affects their contents, including planets that may be forming.

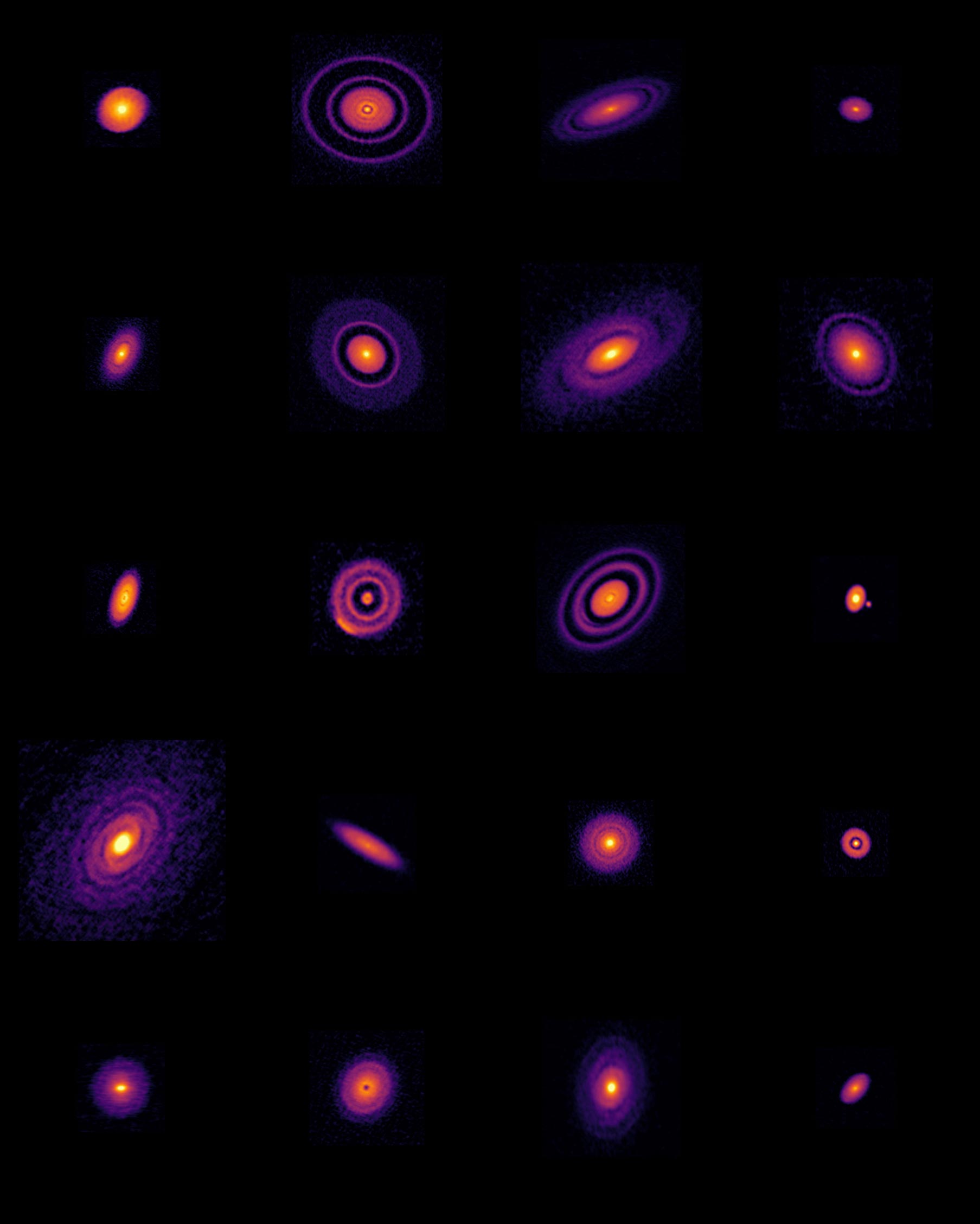

Planetary systems take millions of years to form, which introduces quite a challenge for astronomers. How do you identify which stage they are in, or categorize them? The best approach is to look at lots of examples and keep adding to the data we have – and NASA’s upcoming James Webb Space Telescope will be able to provide an infrared inventory. Researchers using Webb will observe 17 actively forming planetary systems. These particular systems were previously surveyed by the Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array (ALMA), the largest radio telescope in the world, for the Disk Substructures at High Angular Resolution Project (DSHARP).

Webb will measure spectra that can reveal molecules in the inner regions of these protoplanetary disks, complementing the details ALMA has provided about the disks’ outer regions. These inner regions are where rocky, Earth-like planets can start to form, which is one reason why we want to know more about which molecules exist there.

A research team led by Colette Salyk of Vassar College in Poughkeepsie, New York, and Klaus Pontoppidan of the Space Telescope Science Institute in Baltimore, Maryland, seek the details found in infrared light. “Once you switch to infrared light, specifically to Webb’s range in mid-infrared light, we will be sensitive to the most abundant molecules that carry common elements,” explained Pontoppidan.

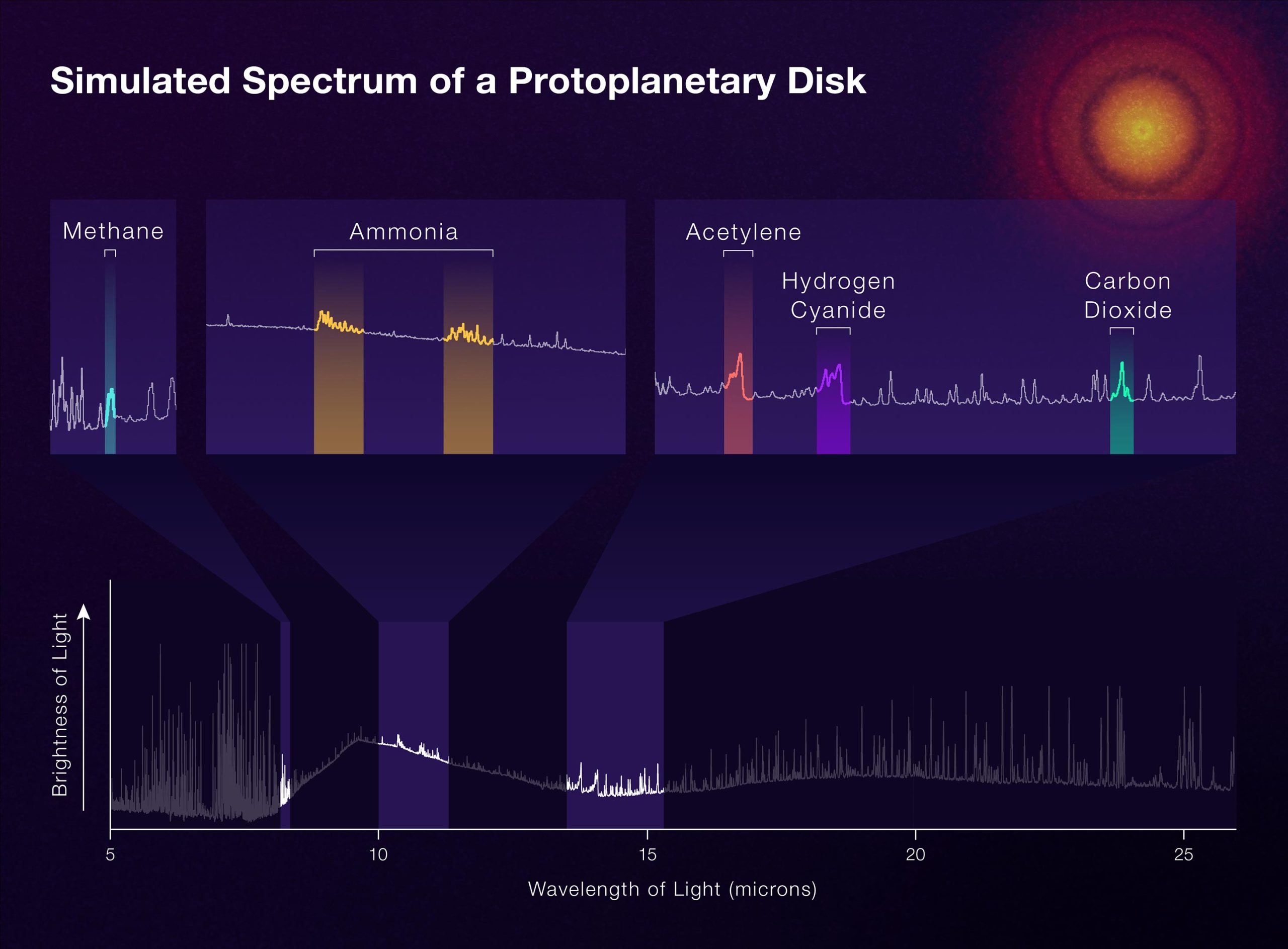

Researchers will be able to assess the quantities of water, carbon monoxide, carbon dioxide, methane, and ammonia – among many other molecules – in each disk. Critically, they will be able to count the molecules that contain elements essential to life as we know it, including oxygen, carbon, and nitrogen. How? With spectroscopy: Webb will capture all the light emitted at the center of each protoplanetary disk as a spectrum, which produces a detailed pattern of colors based on the wavelengths of light emitted. Since every molecule imprints a unique pattern on the spectrum, researchers can identify which molecules are there and build inventories of the contents within each protoplanetary disk. The strength of these patterns also carries information about the temperature and quantity of each molecule.

“Webb’s data will also help us identify where the molecules are within the overall system,” Salyk said. “If they’re hot, that implies they are closer to the star. If they’re cooler, they may be farther away.” This spatial information will help inform models that scientists build as they continue examining this program’s data.

Knowing what’s in the inner regions of the disks has other benefits as well. Has water, for example, made it to this area, where habitable planets may be forming? “One of the things that’s really amazing about planets – change the chemistry just a little bit and you can get these dramatically different worlds,” Salyk continued. “That’s why we’re interested in the chemistry. We’re trying to figure out how the materials initially found in a system may end up as different types of planets.”

If this sounds like a significant undertaking, do not worry – it will be a community effort. This is a Webb Treasury Program, which means that the data is released as soon as it’s taken to all astronomers, allowing everyone to immediately pull the data, begin assessing what’s what in each disk, and share their findings.

“Webb’s infrared data will be intensively studied,” added co-investigator Ke Zhang of the University of Wisconsin–Madison. “We want the whole research community to be able to approach the data from different angles.”

Why the Up-Close Examination?

Let’s step back, to see the forest for the trees. Imagine you are on a research boat off the coast of a distant terrain. This is the broadest view. If you were to land and disembark, you could begin counting how many trees there are and how many of each tree species. You could start identifying specific insects and birds and match up the sounds you heard offshore to the calls you hear under the treetops. This detailed cataloging is very similar to what Webb will empower researchers to do – but swap trees and animals for chemical elements.

The protoplanetary disks in this program are very bright and relatively close to Earth, making them excellent targets to study. It’s why they were surveyed by ALMA. It’s also why researchers studied them with NASA’s Spitzer Space Telescope. These objects have only been studied in depth since 2003, making this a relatively newer field of research. There’s a lot Webb can add to what we know.

The telescope’s Mid-Infrared Instrument (MIRI) provides many advantages. Webb’s location in space means that it can capture the full range of mid-infrared light (Earth’s atmosphere filters it out). Plus, its data will have high resolution, which will reveal many more lines and wiggles in the spectra that the researchers can use to tease out specific molecules.

The researchers were also selective about the types of stars chosen for these observations. This sample includes stars that are about half the mass of the Sun to about twice the mass of the Sun. Why? The goal is to help researchers learn more about systems that may be like our own as it formed. “With this sample, we can start to determine if there are any common features between the disks’ properties and their inner chemistry,” Zhang continued. “Eventually, we want to be able to predict which types of systems are more likely to generate habitable planets.”

Beginning to Answer Big Questions

This program may also help researchers begin to answer some classic questions: Are the forms taken by some of the most abundant elements found in protoplanetary disks, like carbon, nitrogen, and oxygen, “inherited” from the interstellar clouds that formed them? Or does the precise mix of chemicals change over time? “We think we can get to some of those answers by making inventories with Webb,” Pontoppidan explained. “It’s obviously a tremendous amount of work to do – and cannot be done only with these data – but I think we are going to make some major progress.”

Thinking even more broadly about the incredibly rich spectra Webb will provide, Salyk added, “I’m hoping that we’ll see things that surprise us and then begin to study those serendipitous discoveries.”

This research will be conducted as part of Webb General Observer (GO) programs, which are competitively selected using a dual-anonymous review system, the same system that is used to allocate time on the Hubble Space Telescope.

The James Webb Space Telescope will be the world’s premier space science observatory when it launches in 2021. Webb will solve mysteries in our solar system, look beyond to distant worlds around other stars, and probe the mysterious structures and origins of our universe and our place in it. Webb is an international program led by NASA with its partners, ESA (European Space Agency) and the Canadian Space Agency.