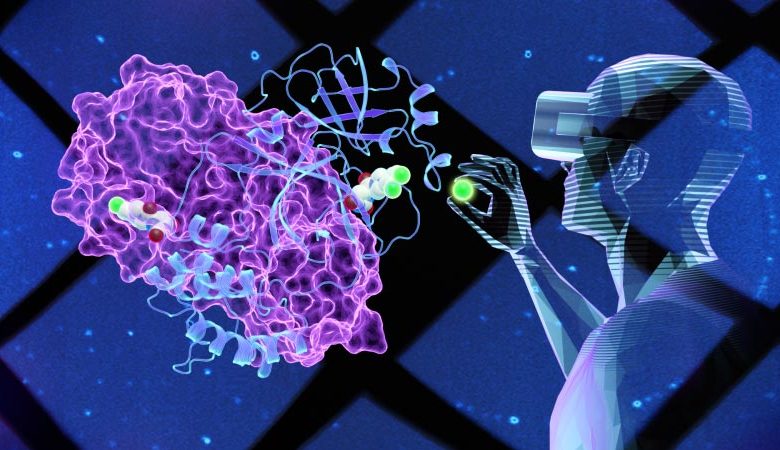

Lead Image: Virtual reality technology enabled scientists to look “inside” the Covid-19 virus and develop a novel molecule that can inhibit its main protease enzyme. Credit: Jill Hemman/ORNL

Virtual reality (VR) technology enables scientists to create 3-D models of an object and then virtually go “inside” to look around to better understand its structure and function.

This is what researchers at the Department of Energy’s (DOE’s) Oak Ridge National Laboratory (ORNL) did to study the SARS-CoV-2 virus that caused the COVID-19 pandemic. The team used neutrons and x-rays to map part of the internal structure of the coronavirus to create an accurate 3-D model. Specifically, the scientists mapped the main protease (Mpro), an enzyme involved in the virus replication, to which they had added a preliminary small molecule discovered using high-speed computer screening.

Using VR to look at the enzyme model, the scientists virtually constructed different small molecules by modifying their structures to see if any newly designed compounds could fit, or bind, to a key site on the Mpro enzyme surface. A strong enough binding could inhibit, or block, the enzyme from functioning, which is vital to stopping the virus from multiplying in patients with COVID-19.

To determine the effects of specific chemical modifications on how tightly the 19 inhibitor candidates bind to the Mpro enzyme, the team synthesized each inhibitor molecule and measured their binding strengths. The stronger the binding, the more effectively the inhibitor would block the enzyme from functioning and the virus from replicating.

One of the test inhibitors, labeled HL-3-68, demonstrated a superior ability to bind to and inhibit the function of Mpro compared to others that were tested. Details of the study, titled “Structural, electronic and electrostatic determinants for inhibitor binding to subsites S1 and S2 in SARS-CoV-2 main protease,” are published in the Journal of Medicinal Chemistry.

“Our study was designed to better understand how molecules bind at the active site of the Mpro enzyme, which plays a key role in SARS-CoV-2 replication,” said lead author Daniel Kneller. “In the process of testing the molecules we designed, we discovered one containing a single extra chlorine atom that showed a greater ability to inhibit Mpro. This novel chemical structure is different than what has been previously studied by the global community and could open new avenues of research with exciting possibilities for combating SARS-CoV-2.”

The active site on the Mpro enzyme is common to other types of coronaviruses and doesn’t appear to easily mutate—presenting an opportunity to possibly design an antiviral treatment that works against multiple SARS-CoV-2 variants and other coronaviruses.

Equally important is that the active site is different from those known in human enzymes, which would minimize the potential for unintended binding that could lead to side effects in patients.

The x-ray measurements and production of the Mpro enzyme samples were performed by the Center for Structural and Molecular Biology using facilities at ORNL’s Spallation Neutron Source (SNS) and resources at the High Flux Isotope Reactor (HFIR). The inhibitor candidates were synthesized by co-authors Hui Li and Peter Bonnesen of the Macromolecular Nanomaterials group at the Center for Nanophase Materials Sciences (CNMS).

“This study combined a plethora of biophysical, biochemical and molecular biology methods, and included virtual reality-assisted structural analysis and small molecule building, bringing together scientists from across ORNL, Argonne National Laboratory, the National Institutes of Health, and the University of Tennessee-Knoxville. The collaborative nature of the study allowed us to uncover the rules small molecule inhibitors must obey when binding to the enzyme in order to be useful for further steps in the long process of drug design and development,” said corresponding author Andrey Kovalevsky.

Added co-corresponding author Peter Bonnesen, “this was a new and exciting project for the CNMS to work on, and it drew on our expertise in synthesizing custom organic molecules for our users. For this project, we provided our SNS colleagues with a couple of candidate molecules at a time. As results came back regarding the molecules’ effectiveness as inhibitors, the team would discuss what adjustments to make to the molecular structure. Then Hui and I would go back to the lab to make these new candidate inhibitors.”

The study also shed light on the Mpro enzyme’s ability to change its shape and change its electrical charge from positive to negative, or from negative to positive, according to the size and structure of the inhibitor molecule it binds to. These features are important to understand when developing an effective inhibitor molecule.

For the neutron scattering research, the scientists used the macromolecular neutron diffractometer (MaNDi) at the SNS for its ability to collect data from the comparatively small samples the team had to work with.

“Due to the pressing nature of research related to the SARS-CoV-2 virus, we were only able to grow relatively small samples of the Mpro enzyme,” said co-author Leighton Coates. “As smaller samples scatter neutrons weakly and this results in “noisy” neutron data, data analysis can be difficult. The time structure of the neutron beam at the MaNDi instrument allowed us to remove most of the noise, thereby increasing the signal-to-noise ratio, giving us much more useful data to work with.”

Next steps for the ORNL researchers include testing chemical modifications of the HL-3-68 inhibitor to determine if any newly designed compounds can bind even better than HL-3-68 to more effectively inhibit the Mpro enzyme and ultimately prevent the coronavirus from replicating.

Meanwhile, the researchers made their data publicly available via the Protein Data Bank to expedite informing and assisting the world’s scientific and medical communities. Of course, more research and tests are necessary to validate the effectiveness and safety of any inhibitor as a COVID-19 treatment. However, this study could offer an opportunity for other scientists to conduct additional research that would benefit billions of people worldwide.

Reference: “Structural, Electronic, and Electrostatic Determinants for Inhibitor Binding to Subsites S1 and S2 in SARS-CoV-2 Main Protease” by Daniel W. Kneller, Hui Li, Stephanie Galanie, Gwyndalyn Phillips, Audrey Labbé, Kevin L. Weiss, Qiu Zhang, Mark A. Arnould, Austin Clyde, Heng Ma, Arvind Ramanathan, Colleen B. Jonsson, Martha S. Head, Leighton Coates, John M. Louis, Peter V. Bonnesen and Andrey Kovalevsky, 27 October 2021, Journal of Medicinal Chemistry.

DOI: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.1c01475

The paper’s other co-authors include Stephanie Galanie, Gwyndalyn Phillips, Audrey Labbé, Kevin L. Weiss, Qiu Zhang, Mark A. Arnould, Austin Clyde, Heng Ma, Arvind Ramanathan, Colleen B. Jonsson, Martha S. Head, and John M. Louis. Hugh O’Neill from ORNL assisted during sample preparation.

COVID-19 research at ORNL was supported in part by the Office of Science’s National Virtual Biotechnology Laboratory, a consortium of DOE national laboratories focused on responding to COVID-19, with funding provided by the Coronavirus CARES Act. This work was also supported by the National Institutes of Health’s National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases.