Lead Image: The picture above depicts the Mississippi River flowing into the Gulf of Mexico. According to researchers at the University of Texas Institute for Geophysics, river sediments and ocean currents helped simple sea life in the Gulf survive a deep-ocean mass extinction 56 million years ago. Credit: U.S. Geological Survey

Research shows how the Gulf of Mexico survived a prehistoric mass extinction.

According to research by the University of Texas Institute for Geophysics (UTIG), an ancient bout of global warming 56 million years ago that acidified oceans and wiped out marine life had a gentler impact in the Gulf of Mexico, where life was protected by the basin’s unique geology.

The results, which were published in the journal Marine and Petroleum Geology, not only shed light on a prehistoric mass extinction but may also assist in attempts to identify oil and gas deposits as well as help scientists predict how present climate change would affect marine species.

The study’s lead researcher, UTIG geochemist Bob Cunningham, also noted that while the Gulf of Mexico is considerably different now, there are still important lessons to be learned about climate change today.

“This event known as the Paleocene-Eocene Thermal Maximum or PETM is very important to understand because it’s pointing towards a very powerful, albeit brief, injection of carbon into the atmosphere that’s akin to what’s happening now,” he said.

By examining a collection of mud, sand, and limestone deposits located around the Gulf, Cunningham and his colleagues looked into the prehistoric era of global warming and its effects on marine life and chemistry.

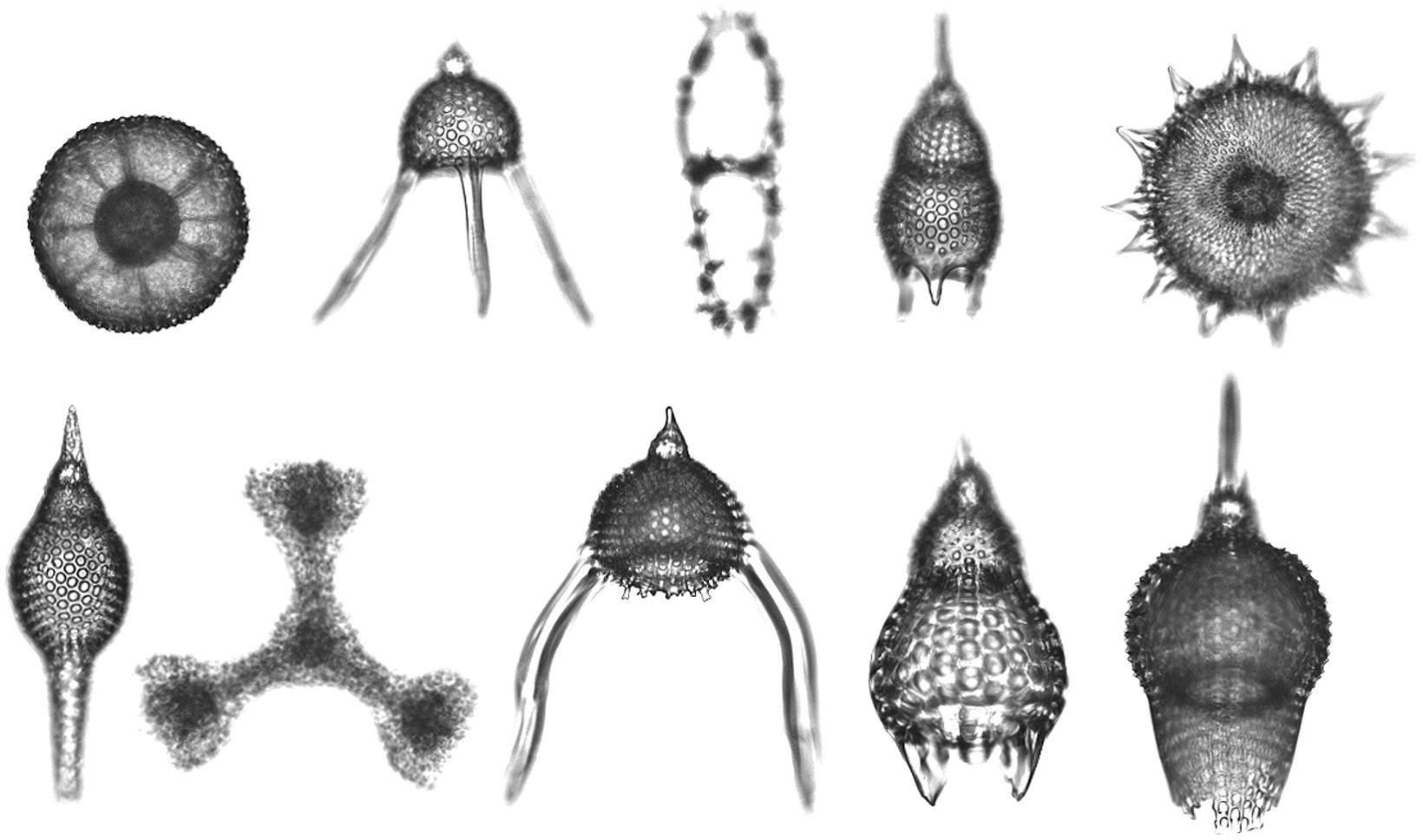

They dug through rock chips left behind by oil and gas drilling and discovered a multitude of radiolarian microfossils, a species of plankton that had unexpectedly flourished in the Gulf during the ancient global warming. They came to the conclusion that radiolarians and other microbes have managed to thrive despite the more unfavorable effects of the Earth’s rising climate thanks to a continual supply of river sediments and circulating ocean waters.

“In a lot of places, the ocean was absolutely uninhabitable for anything,” said UTIG biostratigrapher Marcie Purkey Phillips. “But we just don’t seem to see as severe an effect in the Gulf of Mexico as has been seen elsewhere.”

The reasons for that go back to geologic forces reshaping North America at the time. About 20 million years before the ancient global warming, the rise of the Rocky Mountains had redirected rivers into the northwest Gulf of Mexico – a tectonic shift known as the Laramide uplift – sending much of the continent’s rivers through what is now Texas and Louisiana into the Gulf’s deeper waters.

When global warming hit and North America became hotter and wetter, the rain-filled rivers fire-hosed nutrients and sediments into the basin, providing plenty of nutrients for phytoplankton and other food sources for the radiolarians.

The findings also confirm that the Gulf of Mexico remained connected to the Atlantic Ocean and the salinity of its waters never reached extremes – a question that until now had remained open. According to Phillips, the presence of radiolarians alone – which only thrive in nutrient-rich water that’s no saltier than seawater today – confirmed that the Gulf’s waters did not become too salty. Cunningham added that the organic content of sediments decreased farther from the coast, a sign that deep currents driven by the Atlantic Ocean were sweeping the basin floor.

The research accurately dates closely related geologic layers in the Wilcox Group (a set of rock layers that house an important petroleum system), a feat that can aid in efforts to find undiscovered oil and gas reserves in formations that are the same age. At the same time, the findings are important for researchers investigating the effects of today’s global warming because they show how the water and ecology of the Gulf changed during a very similar period of climate change long ago.

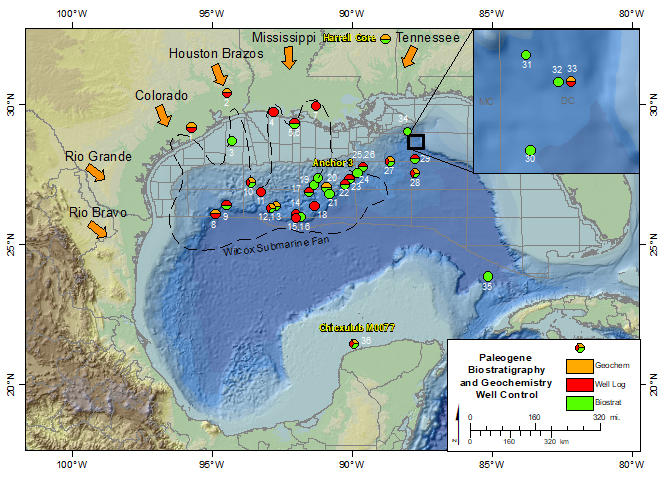

The study compiled geologic samples from 36 industry wells dotted across the Gulf of Mexico, plus a handful of scientific drilling expeditions including the 2016 University of Texas at Austin-led investigation of the Chicxulub asteroid impact, which led to the extinction of non-avian dinosaurs.

For John Snedden, a study co-author and senior research scientist at UTIG, the study is a perfect example of industry data used to address important scientific questions.

“The Gulf of Mexico is a tremendous natural archive of geologic history that’s also very closely surveyed,” he said. “We’ve used this very robust database to examine one of the highest thermal events in the geologic record, and I think it’s given us a very nuanced view of a very important time in Earth’s history.”

Snedden is also program director of the University of Texas’s Gulf Basin Depositional Synthesis, an industry-funded project to map the geologic history of the entire Gulf basin, including the current research. UTIG is a research unit of the University of Texas Jackson School of Geosciences.

Reference: “Productivity and organic carbon trends through the Wilcox Group in the deep Gulf of Mexico: Evidence for ventilation during the Paleocene-Eocene Thermal Maximum” by Robert Cunningham, Marcie Purkey Phillips, John W. Snedden, Ian O. Norton, Christopher M. Lowery, Jon W. Virdell, Craig D. Barrie and Aaron Avery, 8 April 2022, Marine and Petroleum Geology.

DOI: 10.1016/j.marpetgeo.2022.105634