Lead Image: A study finds that algal genes provide answers to questions concerning plant growth and health.

The discovery will help develop heat-tolerant crops and improve algal biofuel production

Plants, like all other known organisms, utilize DNA to pass on traits. Animal genetics often focuses on parentage and lineage, but this can can be challenging in plant genetics since plants can be self-fertile, unlike most animals.

Many plants have unique genetic abilities that make speciation easier, such as being well suited to polyploidy. Plants are special in that they can synthesize energy-dense carbohydrates via photosynthesis, which is accomplished through the usage of chloroplasts. Chloroplasts have their own DNA which allows them to serve as an additional reservoir for genes and genetic diversity, as well as creates an additional layer of genetic complexity not seen in animals. Despite its difficulty, plant genetic research has significant economic implications. Many crops can be genetically modified to increase yield and nutritional value as well as gain pest, herbicide, or disease resistance.

Genes contain all of the instructions that an organism needs to survive, develop, and reproduce. But identifying a gene and understanding what it does are two very different things. Many genes include unexplained instructions, and their functions are unknown to scientists. Recent research conducted by UC Riverside, Princeton University, and Stanford University has revealed the functions of hundreds of genes in algae, some of which are also found in plants. The breakthrough will aid attempts to genetically modify algae for biofuel production and generate climate-resistant agricultural crop types.

“Plant and algae genetics are understudied. These organisms make the foods, fuels, materials, and medicines that modern society relies on, but we have a poor understanding of how they work, which makes engineering them a difficult task,” said corresponding author Robert Jinkerson, an assistant professor of chemical and environmental engineering at UC Riverside. “A common way to learn more about biology is to mutate genes and then see how that affects the organism. By breaking the biology we can see how it works.”

The researchers conducted tests that generated millions of data points using algal mutants and automated tools. The researchers were able to uncover the functional role of hundreds of poorly characterized genes and identify several new functions of previously known genes by analyzing these datasets. These genes have roles in photosynthesis, DNA damage response, heat stress response, toxic chemical response, and algal predator response.

Several of the genes they discovered in algae have counterparts in plants with the same roles, indicating that the algal data can help scientists understand how those genes function in plants as well.

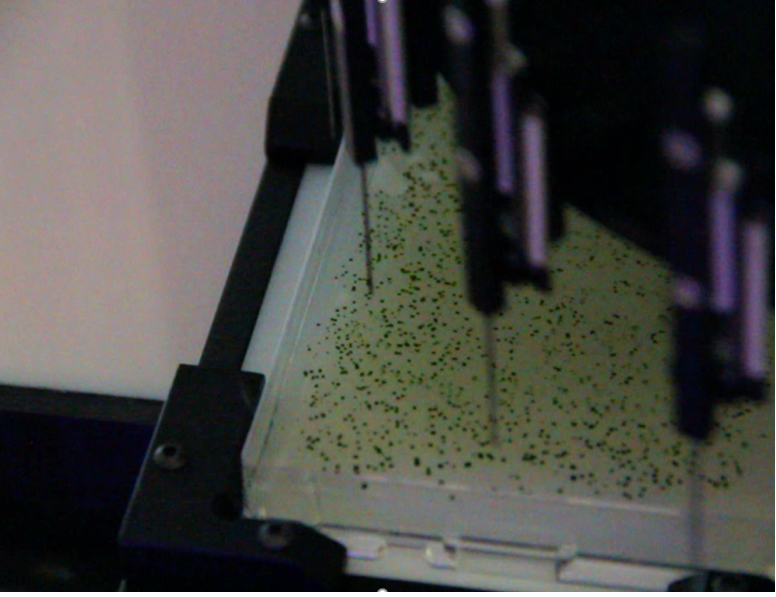

Automated approaches to analyzing tens of thousands of mutants quickly, known as high-throughput methods, are typically used to understand gene function on a genome-wide scale in model systems like yeast and bacteria. This is quicker and more efficient than studying each gene individually. High-throughput methods do not work very well in crop plants, however, because of their larger size and the difficulty of analyzing thousands of plants.

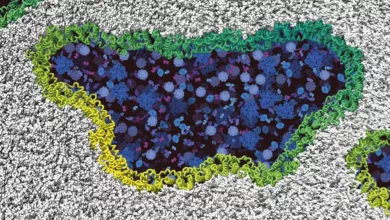

The researchers, therefore, used a high-throughput robot to generate over 65,000 mutants of Chlamydomonas reinhardtii, a type of single-celled green algae closely related to plants and easy to alter genetically. They subjected the mutants to 121 different treatments, which resulted in a dataset of 16.8 million data points. Each mutant had a unique DNA barcode that the team could read to see how that mutant was doing in a specific environmental stress condition.

The group discovered new gene functions in hundreds of genes. For example, they learned that a gene widely found throughout multicellular organisms helps repair damaged DNA. Another 38 genes, when disrupted, caused problems with using energy from light, indicating that these genes played roles in photosynthesis.

Yet another cluster of genes helped the algae process carbon dioxide, a second crucial step in photosynthesis. Other clusters affected the tiny hairs, or cilia, the algae use to swim. This discovery could lead to a better understanding of some human lung and esophageal cancers, which might be partially caused by defective cilia motility.

A newly discovered gene cluster protected the algae from toxins that inhibit cytoskeleton growth. These genes are also present in plants and the discovery could help scientists develop plants that grow well even in some contaminated soils.

Many of the gene functions discovered in algae are also conserved in plants. This information can be used to engineer plants to be more tolerant to heat or cold stress, temperature stress, or improve photosynthesis, all of which will become increasingly important as climate change threatens the world’s food supply.

A better understanding of algae genetics will also improve engineering strategies to make them produce more products, like biofuels.

“The data and knowledge generated in this study is already being leveraged to engineer algae to make more biofuels and to improve environmental stress tolerance in crops,” said Jinkerson.

The research team also included: Sean Cutler at UC Riverside; Friedrich Fauser, Weronika Patena, and Martin C Jonikas at Princeton University; Josep Vilarrasa-Blasi, Masayuki Onishi, and José R Dinneny at Stanford University: Rick Kim, Yuval Kaye, Jacqueline Osaki, Matthew Millican, Charlotte Philp, Matthew Nemeth, and Arthur Grossman at Carnegie Institution; Silvia Ramundo and Peter Walter at UCSF; Setsuko Wakao, Krishna Niyogi, and Sabeeha Merchant at UC Berkeley; and Patrice A Salomé at UCLA.

The research was supported by the U.S. National Institutes of Health, the U.S. National Science Foundation, the Simons Foundation, the Howard Hughes Medical Institute, the German Academic Exchange Service (DAAD), the European Molecular Biology Organization, the Swiss National Science Foundation, and the U.S. Department of Energy.

Reference: “Systematic characterization of gene function in the photosynthetic alga Chlamydomonas reinhardtii” by Friedrich Fauser, Josep Vilarrasa-Blasi, Masayuki Onishi, Silvia Ramundo, Weronika Patena, Matthew Millican, Jacqueline Osaki, Charlotte Philp, Matthew Nemeth, Patrice A. Salomé, Xiaobo Li, Setsuko Wakao, Rick G. Kim, Yuval Kaye, Arthur R. Grossman, Krishna K. Niyogi, Sabeeha S. Merchant, Sean R. Cutler, Peter Walter, José R. Dinneny, Martin C. Jonikas, and Robert E. Jinkerson, 5 May 2022, Nature Genetics.

DOI: 10.1038/s41588-022-01052-9