Lead Image: The drive towards decarbonization and renewable energy presents a significant challenge regarding social justice, especially impacting indigenous peoples and disadvantaged communities. The concept of a ‘just transition’ insists that the cost of the energy overhaul shouldn’t disproportionately impact the vulnerable. However, infrastructural inequalities and costs hinder the accessibility of renewable energy for disadvantaged communities, reinforcing energy insecurity. Columbia Climate School researchers are exploring these social, ethical, and environmental conflicts, recommending more targeted assistance programs to ensure a fair transition.

Mining, Land Grabs, and More: When Decarbonization Conflicts With Human Rights

The shift to renewable energy is exacerbating social injustice issues, particularly affecting indigenous communities and disadvantaged populations. Despite the need for a ‘just transition’, infrastructural inequalities, high costs, and a lack of proper consultation often hamper these communities’ access to renewable energy. Experts recommend increased involvement of local communities, securing their consent for projects, and increased government regulation to ensure a fair energy transition.

The largest lithium deposit in the United States sits on a sacred Indigenous site called Peehee mu’huh in the Paiute language. Also known as Thacker Pass, this area of Nevada has been used by local tribes for generations to harvest food, medicines, and supplies for ceremonies, and may contain ancestral burial sites. It is also believed to be a site in which Indigenous men, women, and children were massacred by white men in 1865. Now, a mining project is moving forward there, the tribes say without proper consultation, and despite concerns about air and water pollution, and potential impacts to endangered species. Undeterred by legal challenges and protests from tribal members and environmental groups, Nevada’s Division of Environmental Protection issued air, water, and mining permits for the Thacker Pass Lithium Mine Project in February 2022.

Preventing the worst effects of climate change requires weaning ourselves off fossil fuels as quickly as possible, a process called decarbonization. It requires mining for elements like lithium for batteries, and cobalt for solar panels. It requires huge swaths of land for installing solar and wind farms. Change is rarely easy, and in this case, it raises a slew of ethical questions. Whose land gets used? Which communities must deal with the mining waste? What happens to coal miners whose jobs become obsolete?

The concept of a ‘just transition’ means that the costs of overhauling our energy system should not fall unfairly on the world’s vulnerable and disadvantaged, and that the benefits of transitioning should be shared equally.

Unfortunately, many decarbonization projects are moving ahead in worrying ways. Scholars across the Columbia Climate School are helping to document these conflicts, and laying down frameworks on how we can move forward responsibly.

Unjust Beginnings

One of the challenges to creating a just transition, said Alexandra Peek, a research associate at Columbia Climate School’s Center on Global Energy Policy, is that people are not starting on a level playing field.

Peek is a junior researcher on a project led by Diana Hernández at Columbia’s Mailman School of Public Health, which has found that Black households across the United States, at all income levels, face energy insecurity, meaning they are not able to meet their basic household energy needs. In predominantly Black neighborhoods, infrastructure is outdated—a legacy from living in segregated neighborhoods, where there has been lower investment and fewer government subsidies, both historically and in the present day.

Another legacy of systemic racism: Thousands of Native American households do not have access to the electric grid at all, Peek added. It costs so much for new transmission lines to be put up—up to $60,000 per mile—that they’re not being put in.

Communities such as these may seem like they would benefit the most from local renewable energy sources, but because of infrastructural inequalities, they may not physically be able to plug in the way affluent neighborhoods can, said Peek. In addition, the cost to individuals can be prohibitively expensive. When she was growing up in El Paso, Texas, Peek looked into putting solar panels on her family’s home, but it wasn’t an affordable option. On top of paying off the solar panels for 20 years, she and her mom would still have to pay a bill for whatever electricity the solar panels couldn’t produce.

“Renewable energy has always been peddled to our communities as the new and better thing for the future,” said Peek. “And on the ground, I didn’t really experience that.”

The incident was one of several that led Peek to examine the political and social impacts of renewable energy. Today, at the Center on Global Energy Policy, she studies energy inequity, environmental racism, and what it means to create a just transition from fossil fuels to renewable energy.

Working with Hernández, Peek and her colleagues are putting together a report on race, infrastructural legacies, and energy insecurity. It will include recommendations for the U.S. Department of Energy on creating more targeted assistance programs that could help to close the gap, allowing more households to meet their basic energy needs.

Unjust Transitions

What does an unjust transition look like? According to a report by the Columbia Center on Sustainable Investment, “Human rights impacts can arise at each phase of the wind and solar value chains.” They can include: land acquisition without allowing communities affected by the project to give or withhold consent or participate in decisions (known as “free, prior, and informed consent”); unfair displacement of Indigenous peoples; forced labor (for example in making solar panel materials); loss of cultural sites and traditions; threats to community health and safety; and violence against human rights defenders. According to the Business and Human Rights Resource Center, the renewable energy sector was the third highest contributor to attacks on human rights defenders from 2015-2020.

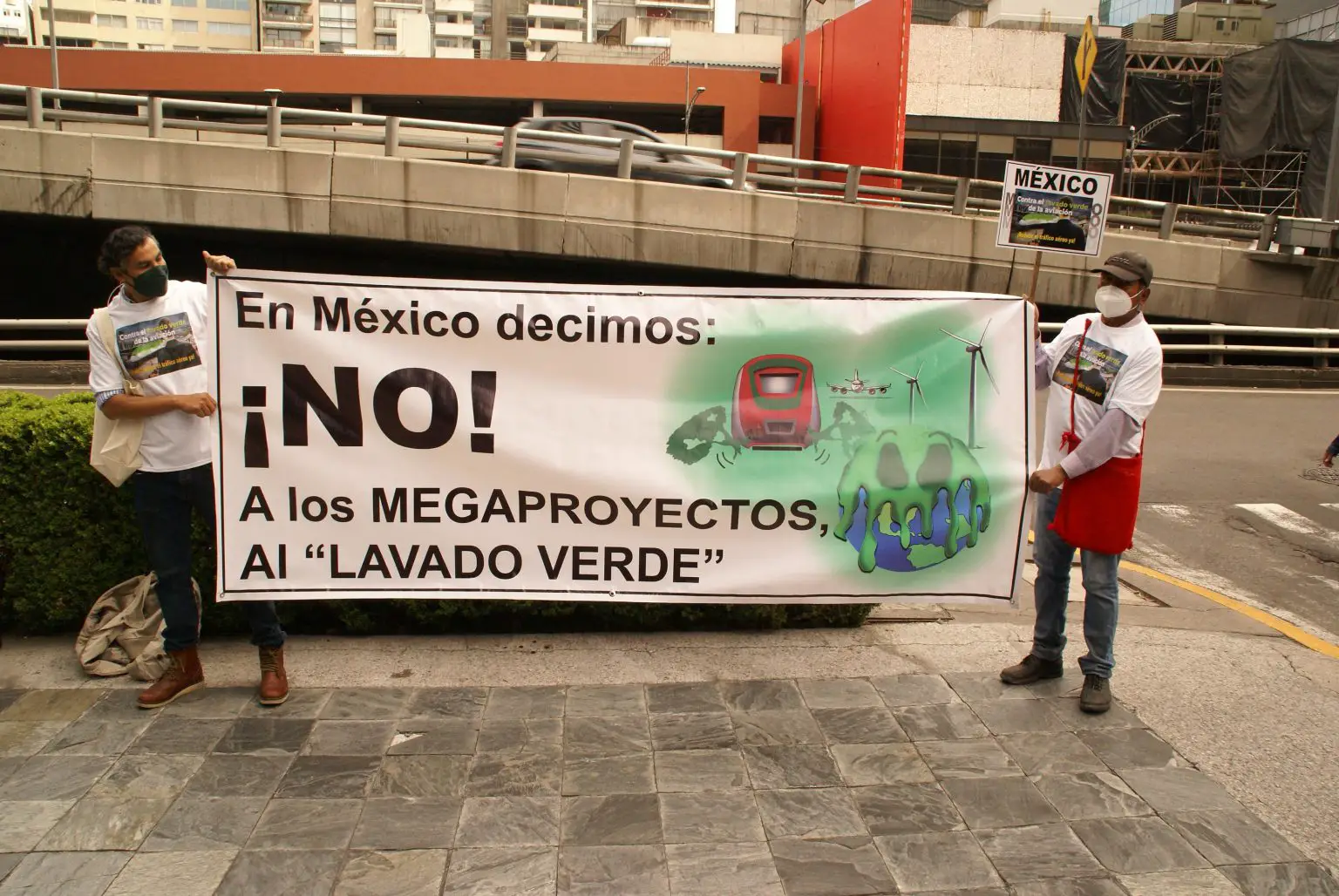

In her studies of how large-scale renewable energy projects affect Indigenous peoples in Latin America, Peek has observed rights violations time and again. In Colombia, for example, the land of the Wayuu people is being auctioned off in the name of the energy transition. Similarly for communal land in Mexico.

“There are a lot of Mexican policies that developers are supposed to work through in order to negotiate land deals with Indigenous people,” she said. “The most important one being free, prior and informed consent. But the conversations have already happened between the government and a foreign investor—they’re just there for the final checkbox.”

Another big problem in Latin America, said Peek, is that the wind and solar power is being siphoned off to the industrial sector. “The biggest wind farm in Mexico was built to power Walmart and Pemex [the Mexican state-owned petroleum company],” she said, “while the people who are actually in proximity to the wind farm, their energy prices went up.”

Rather than keeping the lights on in some faraway Walmart, Peek said that local communities need to have ownership of their own energy systems. Whereas the Indigenous Zapotec people resisted the construction of a large wind farm in the Isthmus of Tehuantepec region of Mexico, for example, studies showed that they craved micro-wind farms that they could own and run themselves, said Peek. Micro-renewable energy technologies have had positive impacts on communities in Hawaii, Alaska, Scotland, and Peru, she added.

Decarbonizing the Right Way

For almost any project or action, impacts are unavoidable. Not decarbonizing fast enough also has an impact: according to a study by Daniel Bressler, a PhD student in Sustainable Development at Columbia University, climate change could cause 83 million excess deaths by 2100. So the question becomes: What impacts are acceptable during decarbonization, and who decides that? How can decarbonization move forward responsibly?

Maria Antonia Tigre, a global climate litigation fellow at the Columbia Climate School’s Sabin Center for Climate Change Law, pointed out that in most cases, communities do not object to renewable energy as a whole, but rather the details of how a project is carried out. She thinks that engaging communities meaningfully and consistently can help to avoid some of these conflicts. “These communities need to be able to participate and to be heard, in terms of what they need,” she said.

Similarly, in a blog post, Sam Szoke-Burke and Kaitlin Cordes from the Columbia Center on Sustainable Investment (CCSI) emphasized the need for free, prior, and informed consent of Indigenous and local communities. “This means ensuring that such communities are sufficiently informed and capacitated, and afforded an opportunity to participate in decision-making — both about whether the project will proceed and, if so, on what terms,” they wrote.

Chris Albin-Lackey, program director at CCSI, says that renewable energy developers could learn a lot from the mining industry’s past mistakes. He identified three areas where mining companies have gone wrong in the past: sweeping aside local community concerns, rather than engaging with them in ways that might be laborious and time-consuming; not delivering the jobs, revenues, and other benefits that were promised; and instead delivering negative impacts on the community and environment.

Some mining companies have gotten more serious about grappling with these issues and are trying to do better. Albin-Lackey said he’s seen some real progress in the way that some key actors in the mining industry are engaging.

“There are blueprints out there for responsible practice,” he said. “There’s no need to reinvent the wheel when it comes to the way that renewable energy projects should navigate some of these potential human rights and sustainability concerns.”

A March 2022 report from CCSI details how commercial solar and wind energy projects can move forward in accordance with human rights. The report offers practical guidance for renewables companies on how to navigate human rights challenges.

“The basic idea is that companies need to have a process in place to make sure that they’re able to correctly identify the most salient human rights risks associated with their own operations,” said Albin-Lackey, “and then take the right steps to mitigate those risks.”

In addition to asking companies to do better, Albin-Lackey thinks there needs to be stronger government oversight. “Governments have generally failed to rise to the challenge of putting in place the kind of regulation that’s necessary to manage these risks,” he said. “Instead, we have all come to rely more and more on initiatives that are essentially voluntary.”

A Just Transition Is Possible

In a paper, Maria Antonia Tigre of the Sabin Center and several colleagues have collected and compared lawsuits around just transitions in Latin America.

So far, they’ve found 21 cases in Mexico, Brazil, Chile, and Colombia. “The reason why we’re doing this project is because we believe we will see a lot more of these types of cases in the very near future,” said Tigre.

Tigre said the lawsuits they’ve found so far tend to focus on how communities are being integrated in the projects, such as whether free, prior and informed consent took place, or whether workers were integrated in the decision-making related to decarbonization. Several of the cases have been successful in promoting a fair energy transition.

In one case in Chile three union workers sued the Ministry of Energy for not involving laborers in the state’s plan to find new roles for workers affected by the decommissioning of fossil fuel projects. In 2021, the Chilean Supreme Court ruled in favor of the workers, declaring that the lack of consultation violated the government’s obligation to ensure a just transition.

In an upcoming paper, Liv Yoon, a former postdoctoral research scholar at the Columbia Climate School, documents one community’s successful bid for a just transition. In the Town of Tonawanda, New York, when the coal-fired Huntley power plant was facing shut down due to low natural gas prices, the town saw a sharp drop in tax revenue. Many public services were discontinued. Two schools closed, and 140 teachers lost their jobs.

Working together, environmental justice advocates and labor groups were able to find other jobs for all the plant workers, and they successfully lobbied their politicians for seven years of funding from New York State to reopen the schools and reinstate some public services.

Watch a short documentary about the Town of Tonawanda’s push for a just transition.

In Yoon’s view, the case shows that a just energy transition is not only possible, but it’s already happening.

“When done well, I think it benefits everyone,” she said, “even the people who don’t believe in climate change.”

No time to lose?

Some environmentalists argue that there is no time to stop and consider the rights of a small community when the fate of the world is at stake.

However, said Albin-Lackey, “when you map out the list of things that’s delaying this terribly overdue transition, this actually isn’t this isn’t a meaningful source of delay. Human rights considerations may make the development of particular projects a little bit slower and more cautious. But, that’s really nothing compared to the larger source of delay, which is political inaction and the lack of the investment that’s necessary.”

Tigre said that although the climate crisis obviously needs to be addressed, running roughshod over human rights is not the ideal solution. “In other times in history, we did similar things for other reasons,” she said, referring to colonialism and labor abuses.

In other words, if the point of the energy transition is to make the world a better place to live in, shouldn’t it start by avoiding the past mistakes that have led to misery, death, and inequality for so many of the world’s most vulnerable?