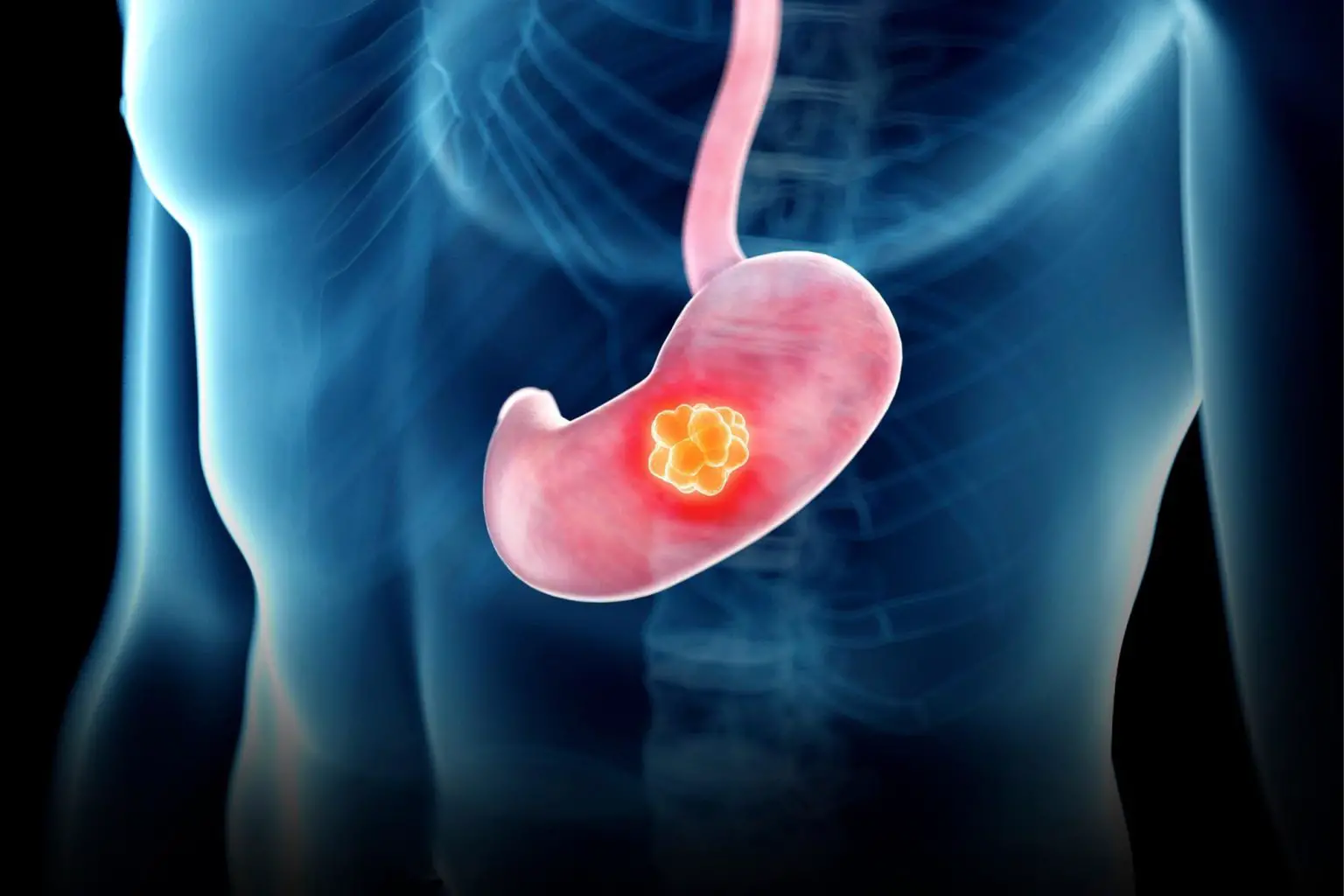

Lead Image: The risk of gastric cancer is significantly amplified by the presence of both a specific stomach microbe, H. pylori, and rare variants in nine genes, according to a study by RIKEN researchers. This research suggests the potential for targeted antibiotic treatments to reduce risk in genetically susceptible individuals.

Working in tandem, a stomach microbe and rare variants found in nine genes greatly increase the risk of gastric cancer over a lifetime.

Genetics has a greater influence in the development of gastric cancer—the fourth-most common cause of cancer death globally—than previously thought, RIKEN researchers have found.

In 2013, actress Angelina Jolie caused a stir when she announced that she had a double mastectomy as a preventative measure against breast and ovarian cancer, which had led to the death of her mother, grandmother, and aunt.

She based the decision on the discovery that she carried a rare variant of the BRCA1 gene that greatly increased her risk of developing breast cancer. The announcement generated much debate about the role that genetics plays in cancer, whether people should be screened, and what action they should take in light of their genome.

This debate was not thought to be directly relevant to gastric cancer, since genetics was not known to play big role in its development. Rather, its main cause was known to be a bacterium called Helicobacter pylori.

A cancer-causing infection

About half the people in the world have H. pylori in their stomachs, having most often acquired the bacterium via contact with another person’s saliva, tooth plaque, vomit, or stool, but also sometimes through contaminated food or water.

Most people are unaware they have the bacteria in their stomachs because it usually doesn’t cause any symptoms. However, in the 1980s, two Australians, Barry Marshall, and Robin Warren, discovered that the bacterium was behind the vast majority of stomach ulcers. Many scientists were initially dismissive of this claim since it flew in the face of the received wisdom that ulcers were primarily caused by stress and other lifestyle factors. However, further work vindicated Marshall and Warren, and they shared a Nobel Prize for the discovery in 2005.

Subsequently, H. pylori was linked with gastric cancer, earning it a classification in the highest-class carcinogens, which include smoking, alcohol, and excessive exposure to sunlight. The role of genetics was considered to be minimal, accounting for a mere 1% to 3% of cases.

A more nuanced perspective

Now, Yoshiaki Usui and Yukihide Momozawa of the RIKEN Center for Integrative Medical Science and their co-workers have shown that the reality of the situation is more nuanced. They have discovered that having two risk factors—H. pylori infection plus carrying certain gene variants—causes the lifetime probability of getting gastric cancer to greatly increase.

Specifically, they found that the probability of someone getting gastric cancer over their lifetime was less than 5% regardless of their genetics if they were free of H. pylori. This risk increased to 14% for people infected with H. pylori, but who didn’t carry one of the rare, high-risk gene variants. But the real surprise was that for people who had both H. pylori and one of the variants found in four genes (which includes the variant that Angelina Jolie has), the risk jumped to more than 45%. These results were published in The New England Journal of Medicine in March 2023.

“I suspected there might be an interaction between the gene variants and H. pylori on gastric cancer risk,” says Usui. “But the actual impact was much larger than I had imagined.”

Empowering carriers of variants

Importantly, this finding offers hope for those carrying one of these gene variants—they can be tested for H. pylori and, if they are infected, they can take antibiotics to eliminate the bacterium, thereby dramatically reducing their risk of contracting gastric cancer. This aspect really appeals to Momozawa.

“As a geneticist, a lot of my work involves identifying genetic risk, and sometimes we can provide only an assessment of risk to carriers, which isn’t very satisfying,” he says. “But this time we can provide genetic risk and an effective treatment. That’s a key point of this study.”

The finding also provides important insights into how gastric cancer develops. H. pylori is known to damage DNA by snapping its double strand in places. At the same time, four of the nine identified genes are involved in a process for fixing damaged DNA. If one of the high-risk variants of these four genes is present, the DNA-repair mechanism doesn’t work and cells revert to another process for repairing DNA that is much more prone to introducing errors.

Thus, H. pylori damages DNA and the gene variants result in errors being introduced when this damage is repaired. This accounts for the high risk of getting gastric cancer when both factors are present.

This finding will also inform research on other cancers. Of the nine high-risk gastric cancer genes (APC, ATM, BRCA1, BRCA2, CDH1, MLH1, MSH2, MSH6 and PALB2) some, such as BRCA1 and BRCA2, have been linked to breast, ovarian, prostate and pancreatic cancer, while MLH1, MSH2 and MSH6 increase the risk of colorectal cancer.

Regional differences

To conduct the study, the team analyzed DNA samples from nearly 12,000 patients with gastric cancer and more than 44,000 people without cancer by drawing on two Japanese cohorts. But since H. pylori is more prevalent in East Asia and the strain in the region is particularly virulent, the results may be far less dramatic in other regions. Usui speculates that had the same study been conducted in USA or Europe, the differences in the gastric cancer risks might have been too small to pick up. This highlights the importance of doing genetic studies in different regions.

Commenting on the study, Nobel laureate Barry Marshall of the University of Western Australia says: “This landmark study by Momozawa et al. has convinced me that H. pylori is the detonator for all kinds of carcinogenic agents, either environmental or genomic. In brief, H. pylori makes everything worse. Much worse.”

Reference: “Helicobacter pylori, Homologous-Recombination Genes, and Gastric Cancer” by Yoshiaki Usui, M.D., Ph.D., Yukari Taniyama, Ph.D., Mikiko Endo, B.Sc., Yuriko N. Koyanagi, M.D., Ph.D., Yumiko Kasugai, M.M.Sc., Isao Oze, M.D., Ph.D., Hidemi Ito, M.D., Ph.D., M.P.H., Issei Imoto, M.D., Ph.D., Tsutomu Tanaka, M.D., Ph.D., Masahiro Tajika, M.D., Ph.D., Yasumasa Niwa, M.D., Ph.D., Yusuke Iwasaki, M.E., Tomomi Aoi, B.Sc., Nozomi Hakozaki, Sadaaki Takata, B.Sc., Kunihiko Suzuki, Chikashi Terao, M.D., Ph.D., Masanori Hatakeyama, M.D., Ph.D., Makoto Hirata, M.D., Ph.D., Kokichi Sugano, M.D., Ph.D., Teruhiko Yoshida, M.D., Ph.D., Yoichiro Kamatani, M.D., Ph.D., Hidewaki Nakagawa, M.D., Ph.D., Koichi Matsuda, M.D., Ph.D., Yoshinori Murakami, M.D., Ph.D., Amanda B. Spurdle, Ph.D., Keitaro Matsuo, M.D., Ph.D. and Yukihide Momozawa, D.V.M., Ph.D., 30 March 2023, The New England Journal of Medicine.

DOI: 10.1056/NEJMoa2211807