NASA just doled out a big chunk of change for the design of private space stations,

On Thursday (Dec. 2), the agency announced that it has awarded three funded Space Act Agreements valued at a total of $415.6 million. The money is split almost evenly among three U.S. companies leading each project: Blue Origin ($130 million), Nanoracks LLC ($160 million) and Northrop Grumman Systems Corp. ($125.6 million).

All three contracts are part of NASA’s Commercial LEO [low Earth orbit) Development program and were given to companies with many years of experience either with human spacecraft or, in the case of Nanoracks, space experiments.

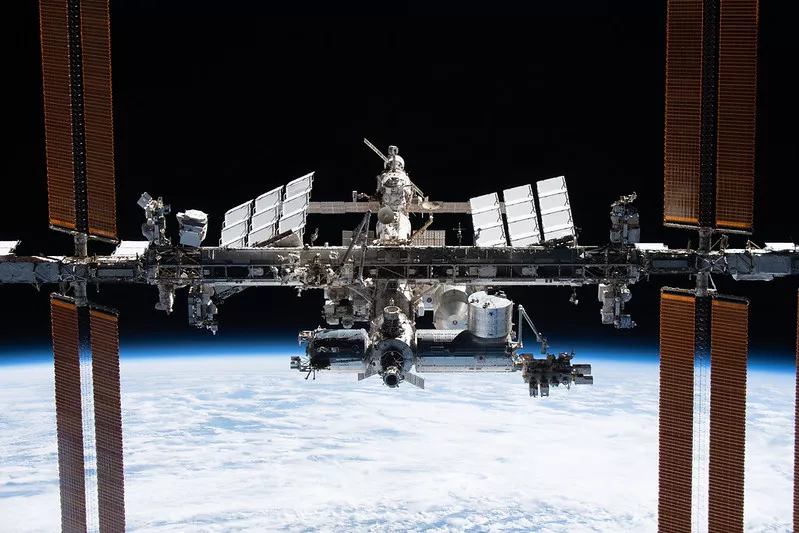

The hope is to get at least one of the companies’ concepts in orbit before 2030, which is when the venerable International Space Station (ISS) is expected to shut down, should all of the orbiting lab’s partners agree to extensions. (The ISS is currently approved to operate only through 2024.)

But whether the companies’ projects will be ready in time, and when the ISS program ends, will be open questions as NASA begins to manage the transition.

The first element of the ISS — the Russian Zarya module — flew to space in 1998. Many other elements of the space station are in their second or third decades of operation. While recent battery and solar panel replacements have helped keep the station healthy, the U.S. Congress is among the entities asking how to manage the ISS program and its end smoothly — ideally in a way to minimize any gaps in American-led access to orbit.

NASA’s space shuttle retired in 2011 after 30 years of service, shutring off direct space access for U.S. astronauts for a decade. Although NASA still had a ride to orbit with the long-running Russian Soyuz spacecraft, an American commercial crew replacement was not ready for humans until 2020, when SpaceX’s Crew Dragon got up and running. And a looming gap seems possible after the ISS program ends, too.

For the moment, the international partnership has agreed to keep the ISS program running until at least 2024. NASA has long argued that the facility will be safe to occupy until at least 2028, and administrator Bill Nelson has endorsed keeping the station running until 2030. If all goes according to plan, at least one of the newly funded commercial space stations should be operational by the time ISS is deorbited, agency officials said.

“We’re making these awards today to help ensure that there is no gap,” Phil McAlister, NASA’s director of commercial spaceflight, told reporters in a conference call Thursday.

A recent report by NASA’s Office of the Inspector General, however, notes that there might be some headwinds getting the new commercial stations off the ground.

The OIG report , which was release Tuesday (Nov. 30), warns that the stakes for timely ISS replacement are high, as any gap could threaten the rapidly growing low Earth economy that NASA is building. Years of commercial research and elements at the ISS will soon include commercial astronauts, starting with an Axiom Space mission scheduled to launch in February 2022.

The OIG report raised concerns about the space station’s advanced age that may make it difficult to maintain, including small leaks (closely monitored and still under investigation) in the Russian Zvezda service module, which has been in orbit since 2000.

The OIG noted that leaks are still occurring despite attempts at repairs. NASA and its partners are investigating multiple possible causes, the OIG report noted; the issue could arise from anything including “fatigue, internal damage, external damage and material defects,” the report stated.

NASA has emphasized, however, that space station crews are under no threat from this maintenance issue. The agency’s response to the report from associate administrator Kathy Lueders added that NASA and Russia’s federal space agency Roscosmos, which operates the Russian modules, are still studying the cracks.

“I agreed with all of those challenges,” McAllister added during the Thursday press conference, referring to the OIG report. “[But] I think these awards today either address or significantly mitigate almost all of the challenges identified in the OIG report.”

As for any extension beyond 2024, ISS director Robyn Gatens told reporters that discussions are ongoing. The current presidential administration and Congress “are supportive,” she said. There’s no timeline yet on a formal announcement, Gatens added.

State reports from Russia — one of the two largest partners on the ISS, along with the U.S. — suggest the country may want to create its own space station later in the 2020s, either due to worries about the aging ISS or to respond to economic sanctions from the United States. Gatens, however, said all space station partners “have indicated their support, and frankly, they’re kind of waiting for the U.S. to go start” the extension process.

Gatens noted that how these partners will access the new private space stations is still being hammered out, but discussions just started with the international consortium to assess their needs. “It’s very important to us [NASA] to keep all of our international partners together with this, to end this transition from ISS to these space stations. The model — how is it going to work? — is kind of wide open.”

NASA predicts future needs for its own commercial activities will include continuous accommodations for at least two crew members, a national orbiting laboratory and at least 200 scientific investigations per year in areas such as technology demonstrations, health research (a key element in planning for deep-space missions) and biological and physical sciences.

The hope is to bring at least one of these commercial stations to orbit in the latter half of the 2020s; each one of the options has the possibility of expansion, NASA said. (The OIG’s report praised NASA’s efforts in starting the procurement process, but noted “inadequate” funding is one of the problems the agency faces in maturing the market.)

Orbital Reef, a Blue Origin- and Sierra Space-led initiative, plans a sort of “mixed-use space business park” (in NASA’s words) catering to users around the world in the latter half of the 2020s. Users will include government, commercial and industry customers. Planned features include reusable space transportation and advanced automation, the latter of which was not widely available when the ISS was being designed.

The Nanoracks-led station is Starlab, set to launch in 2027. This station would host four crew members, double NASA’s requirement, and have a George Washington Carver Science Park with departments in biology, plant habitation, physical science and materials research.

Northrop Grumman’s design (NASA did not disclose a name for the system in the agency’s press release) will include a base module and capabilities in sectors including space tourism, industrial experiments and science. It will have several docking ports for expansion possibilities in areas ranging from artificial gravity facilities to laboratories to crew habitats.

The companies will have until 2025 to formulate and design their “destinations,” as NASA terms the new commercial space stations. Then will come a second phase including certification for crew member use, which will lead to purchase service agreements, NASA said a press release concerning the contracts.

The newly awarded contracts are separate from a call for proposals that NASA issued in 2019 to add commercial modules to the ISS or build separate commercial stations, called “free flyers.” NASA selected Axiom Space for a docking port element in January 2020, but by that August halted the solicitation process without offering further details, according to Space News.

Axiom plans to launch its first module to the ISS in September 2024, then loft three more over the next three years. The company’s four modules could then detach from the ISS and become a free-flying station.