Researchers from the University of Maryland School of Medicine identified a new gene mutation causing heart failure in children, called infantile dilated cardiomyopathy, and successfully reversed its effects using a drug on heart muscle cells derived from the patient’s stem cells. The findings hint towards the development of treatments to manage this condition, currently treated through a heart transplant, by focusing on the discovered genetic mutations that lead to heart failure.

In an effort to determine the cause behind a rare condition that causes heart failure in children, University of Maryland School of Medicine (UMSOM) researchers have identified new gene mutations responsible for the disorder in an infant patient.

After they successfully learned how the mutation works, they were able to use a drug to reverse its effects in heart muscle cells derived from stem cells from the patient.

The findings, recently published in the journal Circulation, suggest that treatments could be developed to manage the condition rather than requiring a heart transplant, which is the standard treatment for this condition in children.

“Although much has been studied about heart failure in adults, there is still much to learn about the genetic causes of heart failure in infants,” said Charles “Chaz” Hong, MD, Ph.D., Melvin Sharoky, MD Professor of Medicine and Physiology, Director of Cardiology Research, and Co-Chief of Cardiovascular Medicine at UMSOM. “Mutations in the gene we identified had been implicated in microcephaly in babies but not yet in human heart disease.”

Infantile dilated cardiomyopathy is a common cause of heart failure — responsible for about half of pediatric heart failure cases — whose cause is most often unknown. Although relatively rare, occurring in about one in 200,000 births, infants with the condition have hearts that fail to contract as effectively, so they are not able to pump as much blood as they should.

This genetic mutation discovered by Dr. Hong and his colleagues was found to normally make a protein found in a cell structure, the centrosome, that functions as a tether for the cell’s skeleton and is best known for its role during cell division.

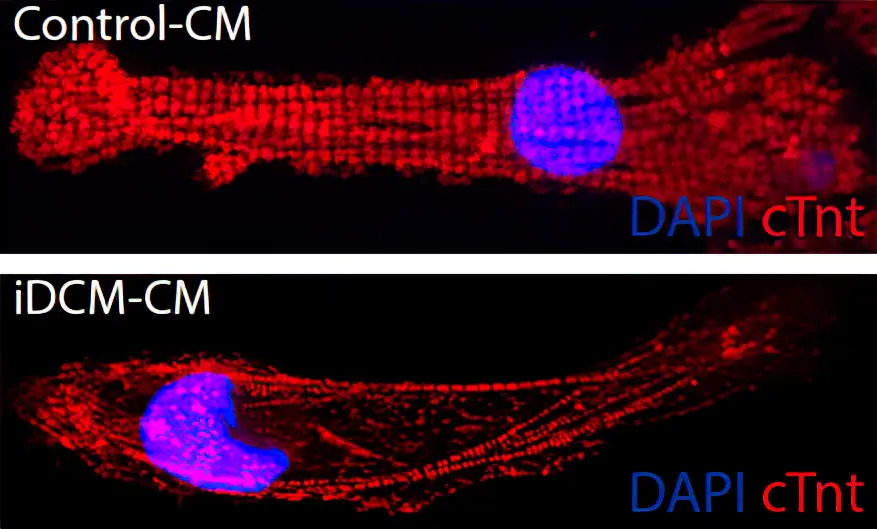

Without this protein, muscle cells in the heart were unable to organize themselves neatly and did not contract as well, which in turn affected the heart’s pumping, the researchers theorized.

“We originally dismissed our findings as artifacts that the cell division machinery would be involved in this kind of heart muscle dysfunction,” said Dr. Hong. “We thought that once the heart cells matured, this cell division machinery completely disappeared, but it turned out, it moves to a new location in the cell and takes on a new role in heart muscle function.”

To identify this gene mutation responsible for infant heart failure, the researchers removed a sample of heart cells from the patient’s diseased heart after it was removed during a transplant. They then converted this heart tissue to stem cells, so they could grow more cells and study them in the lab. They determined that the patient had two different mutations of a gene, one from each parent, that normally encodes for the Rotatin protein.

When the researchers then conducted an experiment to remove this same protein from zebrafish hearts, these hearts developed with signs of heart failure. The researchers also looked at fruit fly hearts missing Rotatin and saw that the muscle cells in these hearts were disorganized and did not contract as well as they should, similar to what happens in infants’ hearts with the disorder.

“This is the first human disease known to be caused by disrupting the transition in centrosome structure which normally occurs shortly after birth,” said Matthew Miyamoto, the first co-author who worked on this project as a rising second-year medical student in Dr. Hong’s laboratory. The researchers then used the drug C19 which was known to organize centrosomes in developing heart muscle cells derived from the patient with infantile dilated cardiomyopathy. The drug restored the organization of the developing heart muscle cells grown in a dish from the patient’s stem cells and their ability to contract.

“Because centrosomes play such a fundamental role in heart muscle development, specifically cell replication, structure, and function, a better understanding of this tissue-specific programmed process will be highly relevant to future cardiac regenerative therapy efforts,” said UMSOM Dean, Mark T. Gladwin, MD, who is also Vice President for Medical Affairs, University of Maryland, Baltimore (UMB), and the John Z. and Akiko K. Bowers Distinguished Professor.

Dr. Hong added, “It is only through collaborations between cardiologists, medical student trainees, and laboratory researchers that allowed this biomedical discovery which we hope will one day translate to medical treatments for children with this condition.”

Patrice Desvigne-Nickens, MD, a medical officer in the Heart Failure and Arrhythmias Branch in the Division of Cardiovascular Sciences at the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI), part of the National Institutes of Health, agreed. “This study makes an important contribution toward understanding the biological underpinnings of infantile dilated cardiomyopathy and its relationship to heart failure,” she said. “We look forward to future studies to clarify and confirm these findings in an effort to improve heart failure outcomes.”

Reference: “Impaired Reorganization of Centrosome Structure Underlies Human Infantile Dilated Cardiomyopathy” by Young Wook Chun, Matthew Miyamoto, Charles H. Williams, Leif R. Neitzel, Maya Silver-Isenstadt, Adrian G. Cadar, Daniela T. Fuller, Daniel C. Fong, Hanhan Liu, Robert Lease, Sungseek Kim, Mikako Katagiri, Matthew D. Durbin, Kuo-Chen Wang, Tromondae K. Feaster, Calvin C. Sheng, M. Diana Neely, Urmila Sreenivasan, Marcia Cortes-Gutierrez, Aloke V. Finn, Rachel Schot, Grazia M.S. Mancini, Seth A. Ament, Kevin C. Ess, Aaron B. Bowman, Zhe Han, David P. Bichell, Yan Ru Su and Charles C. Hong, 27 March 2023, Circulation.

DOI: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.122.060985

This study was funded by grants from the NHLBI, the Maryland Stem Cell Research Fund, and an AOA Carolyn L. Kuckein Student Research Fellowship.

The authors have filed a pending patent on using C19 to treat infantile dilated cardiomyopathy. In accordance with UMB policy, the authors have disclosed their interest in the patent, and the university is managing this relationship to ensure objectivity in the research.