A team of researchers including ones from Stanford and Google have created and observed a new phase of matter, popularly known as a time crystal.

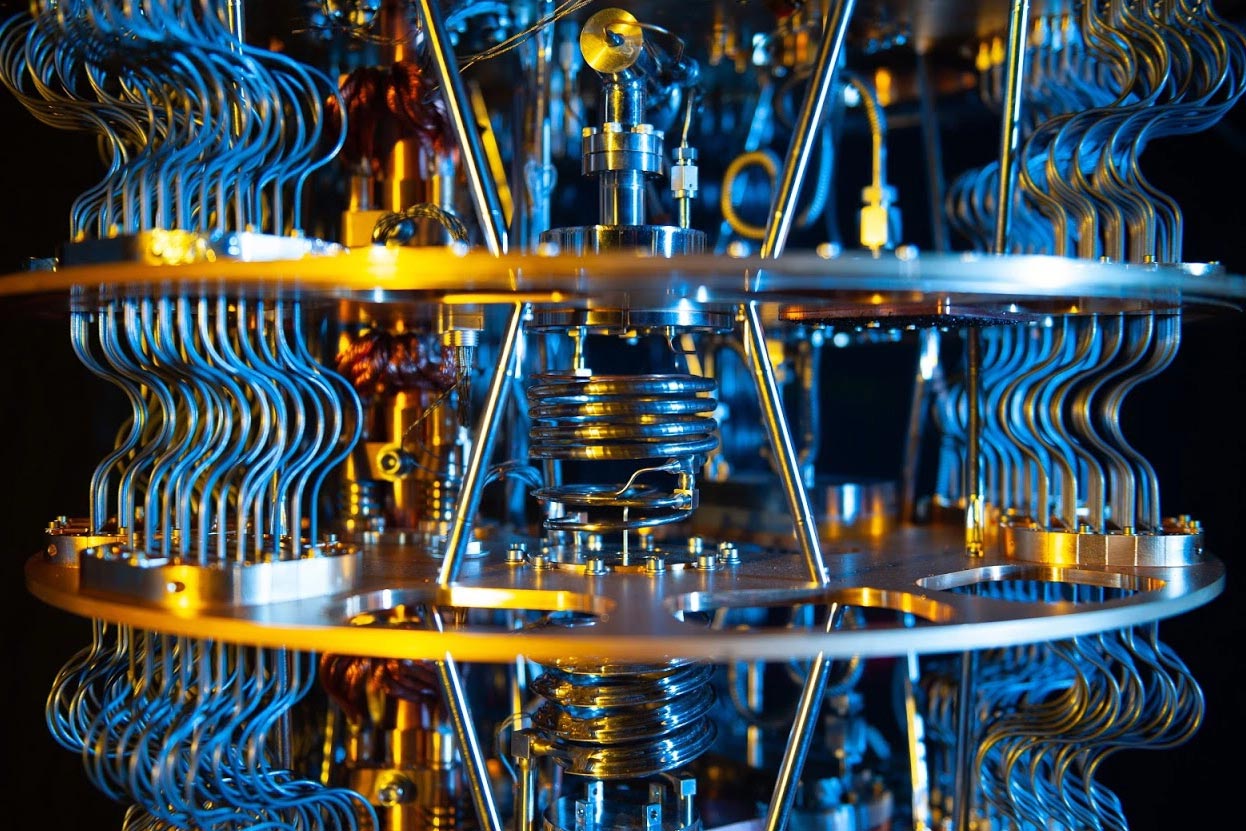

There is a huge global effort to engineer a computer capable of harnessing the power of quantum physics to carry out computations of unprecedented complexity. While formidable technological obstacles still stand in the way of creating such a quantum computer, today’s early prototypes are still capable of remarkable feats.

For example, the creation of a new phase of matter called a “time crystal.” Just as a crystal’s structure repeats in space, a time crystal repeats in time and, importantly, does so infinitely and without any further input of energy – like a clock that runs forever without any batteries. The quest to realize this phase of matter has been a longstanding challenge in theory and experiment – one that has now finally come to fruition.

In research published on November 30, 2021, in the journal Nature, a team of scientists from Stanford University, Google Quantum AI, the Max Planck Institute for Physics of Complex Systems and Oxford University detail their creation of a time crystal using Google’s Sycamore quantum computing hardware.

“The big picture is that we are taking the devices that are meant to be the quantum computers of the future and thinking of them as complex quantum systems in their own right,” said Matteo Ippoliti, a postdoctoral scholar at Stanford and co-lead author of the work. “Instead of computation, we’re putting the computer to work as a new experimental platform to realize and detect new phases of matter.”

For the team, the excitement of their achievement lies not only in creating a new phase of matter but in opening up opportunities to explore new regimes in their field of condensed matter physics, which studies the novel phenomena and properties brought about by the collective interactions of many objects in a system. (Such interactions can be far richer than the properties of the individual objects.)

“Time-crystals are a striking example of a new type of non-equilibrium quantum phase of matter,” said Vedika Khemani, assistant professor of physics at Stanford and a senior author of the paper. “While much of our understanding of condensed matter physics is based on equilibrium systems, these new quantum devices are providing us a fascinating window into new non-equilibrium regimes in many-body physics.”

What a time crystal is and isn’t

The basic ingredients to make this time crystal are as follows: The physics equivalent of a fruit fly and something to give it a kick. The fruit fly of physics is the Ising model, a longstanding tool for understanding various physical phenomena – including phase transitions and magnetism – which consists of a lattice where each site is occupied by a particle that can be in two states, represented as a spin up or down.

During her graduate school years, Khemani, her doctoral advisor Shivaji Sondhi, then at Princeton University, and Achilleas Lazarides and Roderich Moessner at the Max Planck Institute for Physics of Complex Systems stumbled upon this recipe for making time crystals unintentionally. They were studying non-equilibrium many-body localized systems – systems where the particles get “stuck” in the state in which they started and can never relax to an equilibrium state. They were interested in exploring phases that might develop in such systems when they are periodically “kicked” by a laser. Not only did they manage to find stable non-equilibrium phases, they found one where the spins of the particles flipped between patterns that repeat in time forever, at a period twice that of the driving period of the laser, thus making a time crystal.

The periodic kick of the laser establishes a specific rhythm to the dynamics. Normally the “dance” of the spins should sync up with this rhythm, but in a time crystal it doesn’t. Instead, the spins flip between two states, completing a cycle only after being kicked by the laser twice. This means that the system’s “time translation symmetry” is broken. Symmetries play a fundamental role in physics, and they are often broken – explaining the origins of regular crystals, magnets and many other phenomena; however, time translation symmetry stands out because unlike other symmetries, it can’t be broken in equilibrium. The periodic kick is a loophole that makes time crystals possible.

The doubling of the oscillation period is unusual, but not unprecedented. And long-lived oscillations are also very common in the quantum dynamics of few-particle systems. What makes a time crystal unique is that it’s a system of millions of things that are showing this kind of concerted behavior without any energy coming in or leaking out.

“It’s a completely robust phase of matter, where you’re not fine-tuning parameters or states but your system is still quantum,” said Sondhi, professor of physics at Oxford and co-author of the paper. “There’s no feed of energy, there’s no drain of energy, and it keeps going forever and it involves many strongly interacting particles.”

While this may sound suspiciously close to a “perpetual motion machine,” a closer look reveals that time crystals don’t break any laws of physics. Entropy – a measure of disorder in the system – remains stationary over time, marginally satisfying the second law of thermodynamics by not decreasing.

Between the development of this plan for a time crystal and the quantum computer experiment that brought it to reality, many experiments by many different teams of researchers achieved various almost-time-crystal milestones. However, providing all the ingredients in the recipe for “many-body localization” (the phenomenon that enables an infinitely stable time crystal) had remained an outstanding challenge.

For Khemani and her collaborators, the final step to time crystal success was working with a team at Google Quantum AI. Together, this group used Google’s Sycamore quantum computing hardware to program 20 “spins” using the quantum version of a classical computer’s bits of information, known as qubits.

Revealing just how intense the interest in time crystals currently is, another time crystal was published in Science this month. That crystal was created using qubits within a diamond by researchers at Delft University of Technology in the Netherlands.

Quantum opportunities

The researchers were able to confirm their claim of a true time crystal thanks to special capabilities of the quantum computer. Although the finite size and coherence time of the (imperfect) quantum device meant that their experiment was limited in size and duration – so that the time crystal oscillations could only be observed for a few hundred cycles rather than indefinitely – the researchers devised various protocols for assessing the stability of their creation. These included running the simulation forward and backward in time and scaling its size.

“We managed to use the versatility of the quantum computer to help us analyze its own limitations,” said Moessner, co-author of the paper and director at the Max Planck Institute for Physics of Complex Systems. “It essentially told us how to correct for its own errors, so that the fingerprint of ideal time-crystalline behavior could be ascertained from finite time observations.”

A key signature of an ideal time crystal is that it shows indefinite oscillations from all states. Verifying this robustness to choice of states was a key experimental challenge, and the researchers devised a protocol to probe over a million states of their time crystal in just a single run of the machine, requiring mere milliseconds of runtime. This is like viewing a physical crystal from many angles to verify its repetitive structure.

“A unique feature of our quantum processor is its ability to create highly complex quantum states,” said Xiao Mi, a researcher at Google and co-lead author of the paper. “These states allow the phase structures of matter to be effectively verified without needing to investigate the entire computational space – an otherwise intractable task.”

Creating a new phase of matter is unquestionably exciting on a fundamental level. In addition, the fact that these researchers were able to do so points to the increasing usefulness of quantum computers for applications other than computing. “I am optimistic that with more and better qubits, our approach can become a main method in studying non-equilibrium dynamics,” said Pedram Roushan, researcher at Google and senior author of the paper.

“We think that the most exciting use for quantum computers right now is as platforms for fundamental quantum physics,” said Ippoliti. “With the unique capabilities of these systems, there’s hope that you might discover some new phenomenon that you hadn’t predicted.”

Reference: “Time-Crystalline Eigenstate Order on a Quantum Processor” by Xiao Mi, Matteo Ippoliti, Chris Quintana, Ami Greene, Zijun Chen, Jonathan Gross, Frank Arute, Kunal Arya, Juan Atalaya, Ryan Babbush, Joseph C. Bardin, Joao Basso, Andreas Bengtsson, Alexander Bilmes, Alexandre Bourassa, Leon Brill, Michael Broughton, Bob B. Buckley, David A. Buell, Brian Burkett, Nicholas Bushnell, Benjamin Chiaro, Roberto Collins, William Courtney, Dripto Debroy, Sean Demura, Alan R. Derk, Andrew Dunsworth, Daniel Eppens, Catherine Erickson, Edward Farhi, Austin G. Fowler, Brooks Foxen, Craig Gidney, Marissa Giustina, Matthew P. Harrigan, Sean D. Harrington, Jeremy Hilton, Alan Ho, Sabrina Hong, Trent Huang, Ashley Huff, William J. Huggins, L. B. Ioffe, Sergei V. Isakov, Justin Iveland, Evan Jeffrey, Zhang Jiang, Cody Jones, Dvir Kafri, Tanuj Khattar, Seon Kim, Alexei Kitaev, Paul V. Klimov, Alexander N. Korotkov, Fedor Kostritsa, David Landhuis, Pavel Laptev, Joonho Lee, Kenny Lee, Aditya Locharla, Erik Lucero, Orion Martin, Jarrod R. McClean, Trevor McCourt, Matt McEwen, Kevin C. Miao, Masoud Mohseni, Shirin Montazeri, Wojciech Mruczkiewicz, Ofer Naaman, Matthew Neeley, Charles Neill, Michael Newman, Murphy Yuezhen Niu, Thomas E. O’Brien, Alex Opremcak, Eric Ostby, Balint Pato, Andre Petukhov, Nicholas C. Rubin, Daniel Sank, Kevin J. Satzinger, Vladimir Shvarts, Yuan Su, Doug Strain, Marco Szalay, Matthew D. Trevithick, Benjamin Villalonga, Theodore White, Z. Jamie Yao, Ping Yeh, Juhwan Yoo, Adam Zalcman, Hartmut Neven, Sergio Boixo, Vadim Smelyanskiy, Anthony Megrant, Julian Kelly, Yu Chen, S. L. Sondhi, Roderich Moessner, Kostyantyn Kechedzhi, Vedika Khemani and Pedram Roushan, 30 November 2021, Nature.

DOI: 10.1038/s41586-021-04257-w

This work was led by Stanford University, Google Quantum AI, the Max Planck Institute for Physics of Complex Systems and Oxford University. The full author list is available in the Nature paper.

This research was funded by the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA), a Google Research Award, the Sloan Foundation, the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation and the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft.