Engineers have developed new energy-packed lithium-ion batteries that perform well at frigid cold and blazing hot temperatures.

Engineers at the University of California San Diego (UCSD) have developed new lithium-ion batteries that perform well at freezing cold and scorching hot temperatures, while still packing a lot of energy. According to the researchers, this feat was accomplished by developing an electrolyte that is not only versatile and robust throughout a wide temperature range, but also compatible with a high-energy anode and cathode.

The temperature-resilient batteries are described in a paper published the week of July 4 in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS).

Batteries based on this technology could allow electric vehicles in cold climates to travel farther on a single charge. They could also reduce the need for cooling systems to keep the vehicles’ battery packs from overheating in hot climates, said Zheng Chen, a professor of nanoengineering at the UCSD Jacobs School of Engineering and senior author of the study.

“You need high-temperature operation in areas where the ambient temperature can reach the triple digits and the roads get even hotter. In electric vehicles, the battery packs are typically under the floor, close to these hot roads,” explained Chen, who is also a faculty member of the UCSD Sustainable Power and Energy Center. “Also, batteries warm up just from having a current run through during operation. If the batteries cannot tolerate this warmup at high temperature, their performance will quickly degrade.”

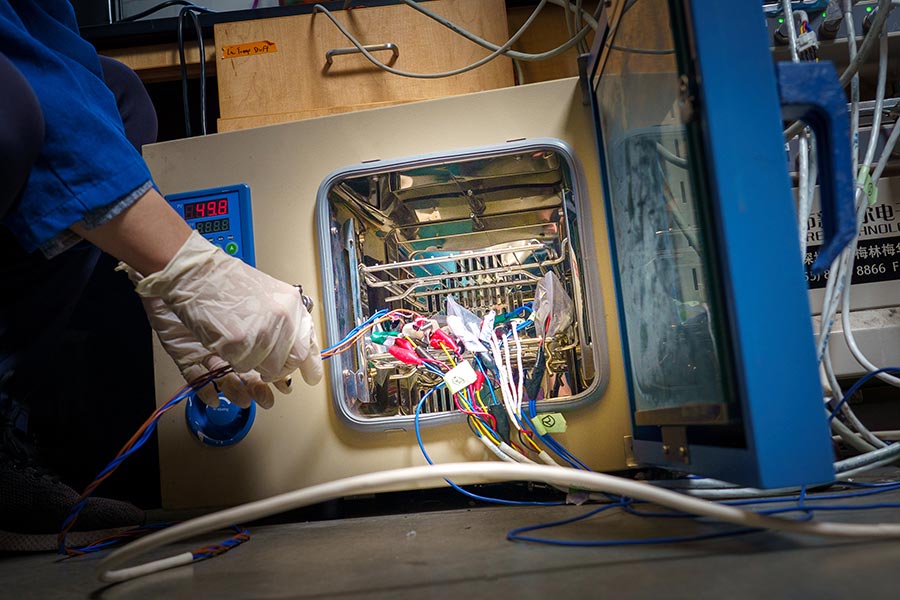

In tests, the proof-of-concept batteries retained 87.5% and 115.9% of their energy capacity at -40 and 50 °C (-40 and 122 °F), respectively. They also had high Coulombic efficiencies of 98.2% and 98.7% at these temperatures, respectively, which means the batteries can undergo more charge and discharge cycles before they stop working.

The batteries that Chen and colleagues developed are both cold and heat-tolerant thanks to their unique electrolyte. It is made of a liquid solution of dibutyl ether mixed with a lithium salt. A special feature of dibutyl ether is that its molecules bind weakly to lithium ions. In other words, the electrolyte molecules can easily let go of lithium ions as the battery runs. This weak molecular interaction, the researchers had discovered in a previous study, improves battery performance at sub-zero temperatures. Plus, dibutyl ether can easily take the heat because it stays liquid at high temperatures (it has a boiling point of 141 °C, or 286 °F).

Stabilizing lithium-sulfur chemistries

What’s also special about this electrolyte is that it is compatible with a lithium-sulfur battery, which is a type of rechargeable battery that has an anode made of lithium metal and a cathode made of sulfur. Lithium-sulfur batteries are an essential part of next-generation battery technologies because they promise higher energy densities and lower costs. They can store up to two times more energy per kilogram than today’s lithium-ion batteries—this could double the range of electric vehicles without any increase in the weight of the battery pack. Also, sulfur is more abundant and less problematic to source than the cobalt used in traditional lithium-ion battery cathodes.

But there are problems with lithium-sulfur batteries. Both the cathode and anode are super reactive. Sulfur cathodes are so reactive that they dissolve during battery operation. This issue gets worse at high temperatures. And lithium metal anodes are prone to forming needle-like structures called dendrites that can pierce parts of the battery, causing it to short-circuit. As a result, lithium-sulfur batteries only last up to tens of cycles.

“If you want a battery with high energy density, you typically need to use very harsh, complicated chemistry,” said Chen. “High energy means more reactions are happening, which means less stability, more degradation. Making a high-energy battery that is stable is a difficult task itself—trying to do this through a wide temperature range is even more challenging.”

The dibutyl ether electrolyte developed by the UCSD research team prevents these issues, even at high and low temperatures. The batteries they tested had much longer cycling lives than a typical lithium-sulfur battery. “Our electrolyte helps improve both the cathode side and anode side while providing high conductivity and interfacial stability,” said Chen.

The team also engineered the sulfur cathode to be more stable by grafting it to a polymer. This prevents more sulfur from dissolving into the electrolyte.

The next steps include scaling up the battery chemistry, optimizing it to work at even higher temperatures, and further extending cycle life.

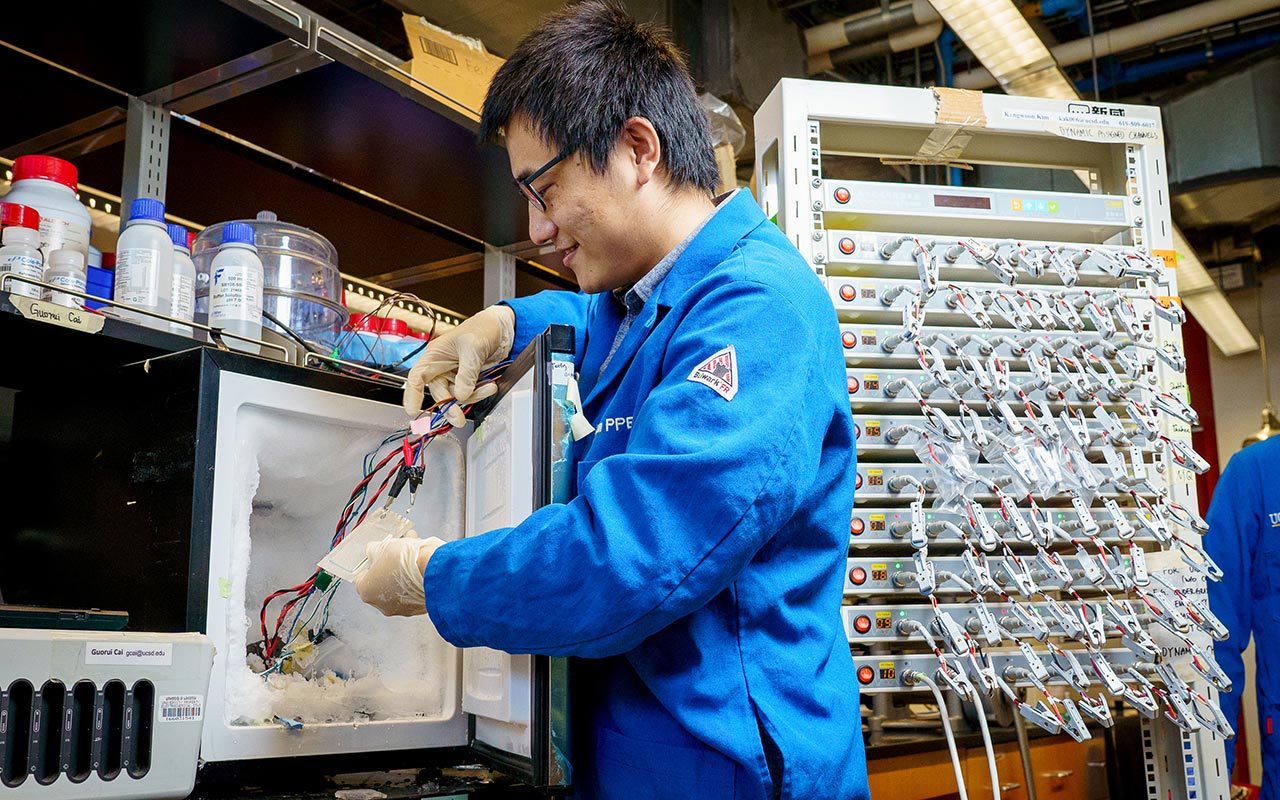

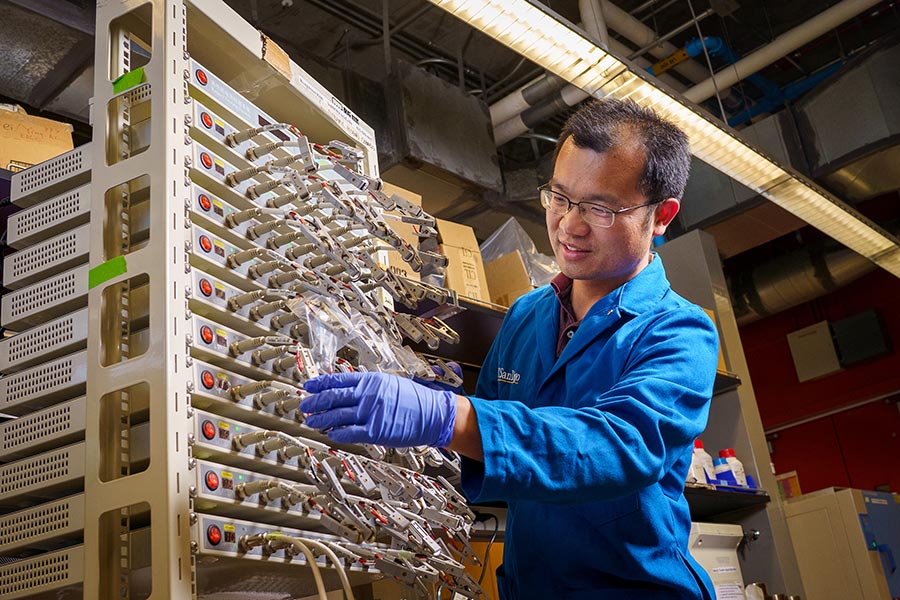

Reference: “Solvent selection criteria for temperature-resilient lithium-sulfur batteries.” Co-authors include Guorui Cai, John Holoubek, Mingqian Li, Hongpeng Gao, Yijie Yin, Sicen Yu, Haodong Liu, Tod A. Pascal and Ping Liu, all at UC San Diego. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

This work was supported by an Early Career Faculty grant from NASA’s Space Technology Research Grants Program (ECF 80NSSC18K1512), the National Science Foundation through the UC San Diego Materials Research Science and Engineering Center (MRSEC, grant DMR-2011924), and the Office of Vehicle Technologies of the U.S. Department of Energy through the Advanced Battery Materials Research Program (Battery500 Consortium, contract DE-EE0007764). This work was performed in part at the San Diego Nanotechnology Infrastructure (SDNI) at UC San Diego, a member of the National Nanotechnology Coordinated Infrastructure, which is supported by the National Science Foundation (grant ECCS-1542148).