A different perspective can do wonders. Perceiving things from a different angle can both metaphorically and literally allow people to see things differently. And in space, there are an almost infinite number of angles that objects can be observed from. Like all perspectives, some are more informative than others. Sometimes those informative perspectives are also the hardest to reach.

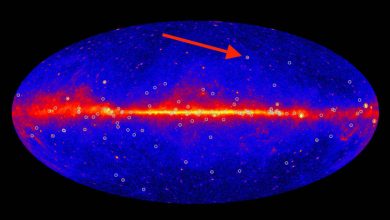

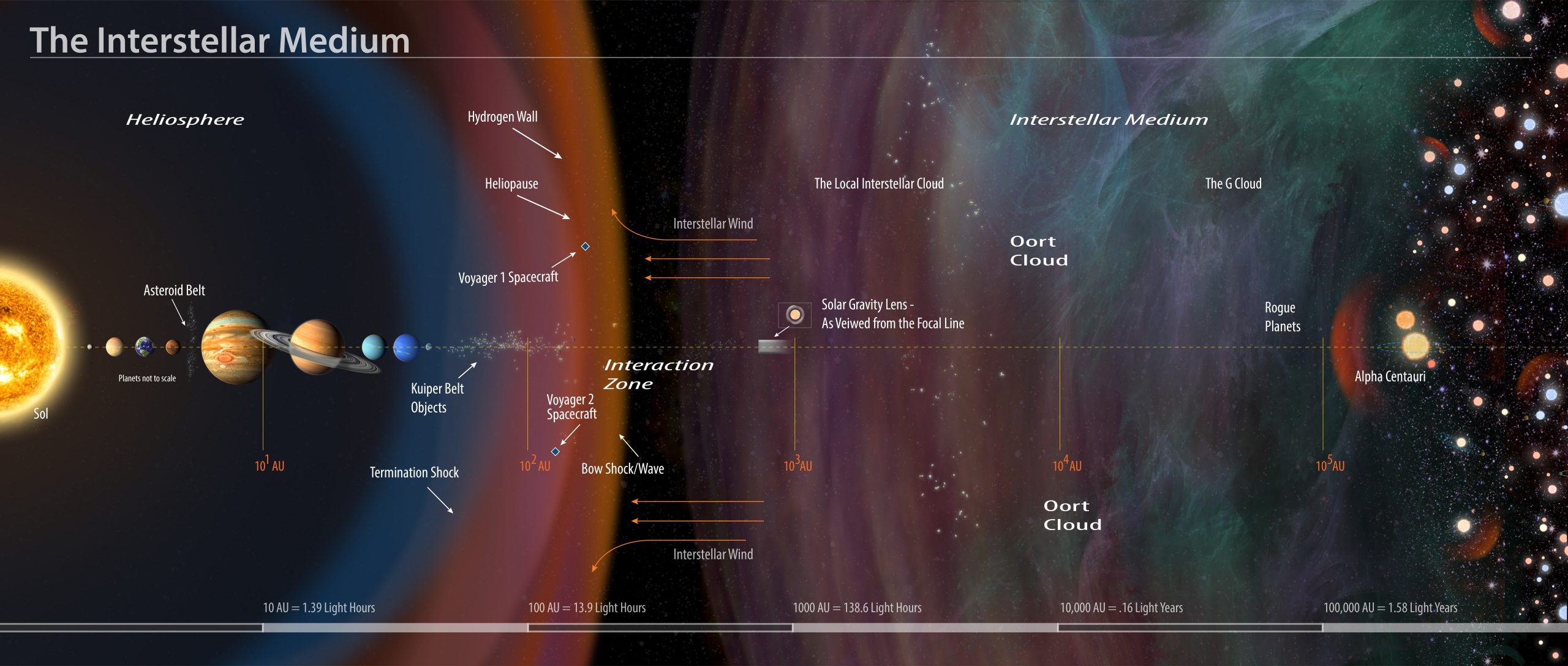

When the four-decades-old Voyager 1 and Voyager 2 spacecraft entered interstellar space in 2012 and 2018, respectively, scientists celebrated. These plucky spacecraft had already traveled 120 times the distance from the Earth to the sun to reach the boundary of the heliosphere, the bubble encompassing our solar system that’s affected by the solar wind. The Voyagers discovered the edge of the bubble but left scientists with many questions about how our Sun interacts with the local interstellar medium. The twin Voyagers’ instruments provide limited data, leaving critical gaps in our understanding of this region.

Voyager’s two probes did an excellent job in allowing humanity to access some difficult new perspectives simply given their distance from the Earth. But now a team of over 500 scientists and volunteers is urging NASA to go even further to find a better perspective by sending a satellite to a distance 1000 times the distance from the Sun to the Earth – almost 10 times how far the Voyagers have traveled in over 35 years.

The project, currently known as the “Interstellar Probe”, is headed by Dr. Elena Provornikova the Interstellar Probe heliophysics lead from the Johns Hopkins Applied Physical Lab (APL) in Maryland. She leads a team of over 500 people to help define what the objectives of such an ambitious mission would be. “There are truly outstanding science opportunities that span heliophysics, planetary science, and astrophysics,” Provornikova says.

“The Interstellar Probe will go to the unknown local interstellar space, where humanity has never reached before,” says Provornikova. “For the first time, we will take a picture of our vast heliosphere from the outside to see what our solar system home looks like.”

Provornikova and her colleagues will discuss the heliophysics science opportunities for the mission at the European Geosciences Union (EGU) General Assembly 2021.

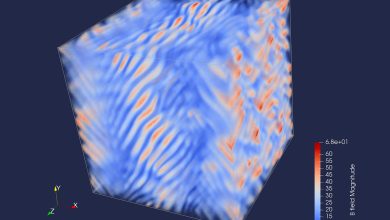

Some mysteries the team hopes to solve with the mission include: how the sun’s plasma interacts with interstellar gas to create our heliosphere; what lies beyond our heliosphere; and what our heliosphere even looks like. The mission plans to take “images” of our heliosphere using energetic neutral atoms, and perhaps even “observe extragalactic background light from the early times of our galaxy formation — something that can’t be seen from Earth,” Provornikova says. Scientists also hope to learn more about how our sun interacts with the local galaxy, which might then offer clues as to how other stars in the galaxy interact with their interstellar neighborhoods, she says.

Some of the primary science will undoubtedly focus on the heliosphere, the area surrounding our star that is subject to the solar wind. Voyager found the edge, but their instruments were not designed to study the phenomena, so they left many unanswered questions in their wake. The new mission would attempt to pick up where they left off.

One of those unanswered questions is about how exactly interstellar gas interacts with the sun’s plasma, which is the current theory for how the heliosphere is created. Additional information about the heliosphere that the team hopes to collect includes what exactly the heliosphere itself looks like and how it is affected as the sun moves through the galaxy.

But studying the heliosphere won’t be the only goal of the mission. Everything from planetary science to observing extragalactic background light is on the menu for possible inclusion in the mission. Part of the selling point of the Interstellar Probe is the wide variety of new observations it would be able to take that have never been available before.

Those selling points are included in the “pragmatic concept study” that Dr. Provornikova and her team will complete this year after a four year effort. Their final report will include proposed details of the mission, including science objectives, instrument payloads, and potential trajectories.

As with many proposed missions there is still a long way to go before any data from a new perspective is actually gathered. Right now the mission would plan to launch in the 2030s and reach the 1000 AU target around 15 years later. No matter when it actually reaches its destination, with the proper planning and resources, the Interstellar Probe will result in a completely new perspective for science.

The heliosphere is also important because it shields our solar system from high-energy galactic cosmic rays. The sun is traveling around in our galaxy, going through different regions in interstellar space, Provornikova says. The sun is currently in what is called the Local Interstellar Cloud, but recent research suggests the sun may be moving toward the edge of the cloud, after which it would enter the next region of interstellar space — which we know nothing about. Such a change may make our heliosphere grow bigger or smaller or change the amount of galactic cosmic rays that get in and contribute to the background radiation level at Earth, she says.

This is the final year of a four-year “pragmatic concept study,” in which the team has been investigating what science could be accomplished with this mission. At the end of the year, the team will deliver a report to NASA that outlines potential science, example instrument payloads, and example spacecraft and trajectory designs for the mission. “Our approach is to lay out the menu of what can be done in such a space mission,” Provornikova says.

The mission could launch in the early 2030s and would take about 15 years to reach the heliosphere boundary — a pace that’s quick compared to the Voyagers, which took 35 years to get there. The current mission design is planned to last 50 years or more.

Reference: “Unique heliophysics science opportunities along the Interstellar Probe journey up to 1000 AU from the Sun” by Elena Provornikova, Pontus C. Brandt, Ralph L. McNutt, Jr., Robert DeMajistre, Edmond C. Roelof, Parisa Mostafavi, Drew Turner, Matthew E. Hill, Jeffrey L. Linsky, Seth Redfield, Andre Galli, Carey Lisse, Kathleen Mandt, Abigail Rymer and Kirby Runyon, 26 April 2021, EGU General Assembly 2021.