Nvidia held their annual spring GPU Technology Conference (GTC), virtually once again on 12th April this year due to the pandemic raging across the world. The company unveiled its first ever Arm-based CPU, called Grace in honor of the famous American programmer Grace Hopper. The announcement of the new Arm CPU follows Nvidia’s 2019 declaration of intent to fully embrace Arm and its September 2020 bid to acquire Arm for $40 billion.

We’ve barely heard a peep out of Nvidia on the CPU front for years, after the lackluster arrival of its Project Denver CPU and its associated Tegra K1 mobile processors in 2014. But now, the company’s getting back into CPUs in a big way with the new Nvidia Grace, an Arm-based processing chip specifically designed for AI data centers.

Meet the NVIDIA Grace #CPU, leveraging the flexibility of @Arm’s data center architecture and designed from the ground up to accelerate the largest HPC and AI workloads. #GTC21 https://t.co/PHDaxrfzQv pic.twitter.com/uck0akde3a

— NVIDIA GTC (@NVIDIAGTC) April 12, 2021

Grace is expected to debut in 2023 with two HPC centers leading the way. The Swiss National Supercomputing Centre (CSCS) and the U.S. Department of Energy’s Los Alamos National Laboratory are the first to announce plans to build Grace-powered supercomputers in partnership with HPE and Nvidia.

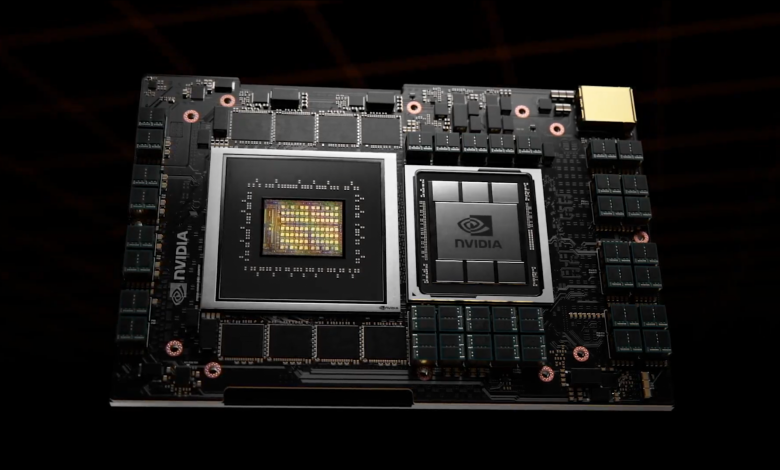

Using future-generation Arm Neoverse cores and next-generation Nvidia NVLink interconnect technology, Grace has been designed for tight coupling with Nvidia GPUs to power the very largest AI and HPC workloads, according to Nvidia.

In his third virtual GTC “kitchen keynote,” Nvidia CEO Jensen Huang said the chip, combined with Nvidia’s GPUs and high-performance networking from its Mellanox division, gives Nvidia “the third foundational technology for computing, and the ability to re-architect every aspect of the datacenter for AI.”

Using fourth-generation NVLink technology, Grace enables 900 GB/s of bidirectional bandwidth between the CPU and GPU, driving significantly higher aggregate bandwidth over today’s standard servers (~30x higher says Nvidia). The new architecture also provides cache coherence with a single memory address space, unifying system and HBM GPU memory to simplify programmability.

“Grace highlights the beauty of Arm,” Huang said. “Their IP model allowed us to create the optimal CPU for this application, which achieves x-factor speed up.” He said the Grace CPU will deliver 300 SPECint rate with a total of over 2,400 SPECint CPU performance per eight-GPU DGX. In comparison, today’s eight-GPU DGX A100 achieves 450 SPECint rate.

Unlike most GPU-accelerated systems on the market today, which have a two-to-one or higher ratio of GPUs to CPUs (with four-to-one being something of a sweet spot), Grace-based systems will be architected with a one-to-one ratio of CPU to GPU, according to Nvidia. While the company is not yet announcing products, based on Jensen’s SPECint performance claims, it seems an eight-GPU DGX server with eight Grace CPUs is in the works.

Nvidia’s high-bandwidth, next-generation NVLink fabric will connect all the elements in the future DGX system, including the two CPUs. The only other server to have native NVLink support on the CPU was the IBM Power platform, which was the basis for the Summit and Sierra supercomputers (currently ranked #2 and #3 in the world), installed at Oak Ridge National Lab and Lawrence Livermore Lab, respectively.

Grace also has a new memory subsystem, leveraging LPDDR5X memory technology, which has has twice the bandwidth of today’s DDR4, and is 10 times more energy efficient, according to Nvidia. “We optimize this memory subsystem to support server class reliability through mechanisms like ECC and redundancy,” said Paresh Kharya, senior director of accelerated computing at Nvidia, in a pre-briefing last week.

“This efficiency means you can divert more power towards compute rather than moving the bits around,” said Kharya.

Grace will be supported by Nvidia’s HPC software development kit and its CUDA and CUDA-X libraries.

CSCS and Los Alamos both have Grace-based supercomputers under development with expected delivery in 2023. The CSCS “Alps” system is being billed as the world’s most powerful AI-capable supercomputer, expected to deliver 20 exaflops of performance for AI, using Nvidia’s mixed-precision arithmetic and sparsity features. Based on the HPE Cray XE (formerly Shasta) architecture, Alps will advance the boundaries of whole-earth scale weather and climate simulation, quantum chemistry and quantum physics for the Large Hadron Collider.

Nvidia reports that due to its scale and tight coupling between the CPUs and GPUs, Alps will be able to train the massive GPT-3 language processing model in only two days. That is seven times faster than the Nvidia Selene supercomputer, which is currently ranked number five on the Top500 (with 63.5 Linpack petaflops and 2.8 “AI exaflops”), according to Nvidia.

Scientists at Los Alamos report they are taking delivery of Nvidia A100 GPUs as a first step to receiving a Grace CPU-based system that will facilitate modeling, simulation, and data analysis in support of the lab’s mission. Los Alamos expects to be the first U.S. customer for the new Grace CPUs and will be part of a multi-year codesign collaboration that will inform hardware and software design choices for the benefit of scientific discovery. The lab’s Grace system is also being built by HPE, implementing its Cray EX architecture.

“We’re thrilled by the enthusiasm of the supercomputing community, welcoming us to make Arm a top-notch scientific computing platform,” said Huang today.

“Arm is the most popular CPU in the world, for good reason. It’s super energy-efficient and it’s open licensing model inspires a world of innovators to create product around it,” the CEO said.

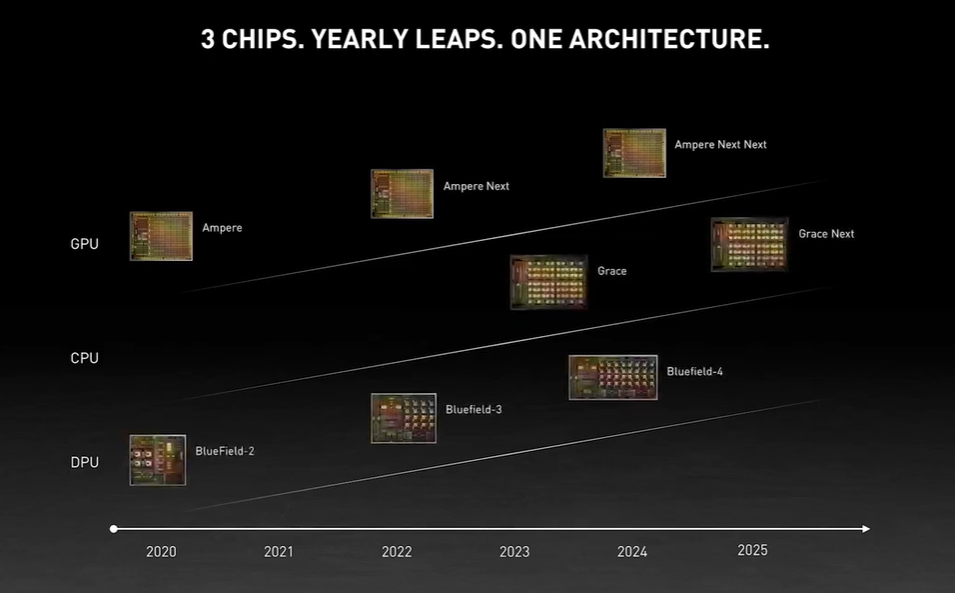

Nvidia’s roadmap now includes three chips: the GPU, CPU and DPU. “Each chip architecture has a two-year rhythm, and likely a kicker in between,” Huang said. “One year we’ll focus on x86 platforms, one year we’ll focus on Arm platforms. The Nvidia architecture and platforms will support x86 and Arm, whatever customers and markets prefer.”

The arrival of Grace has in some sense been a decade in the making, stretching back to Nvidia’s 2011 “Project Denver,” the company’s ambitious plan to build a general-purpose Arm CPU capable of powering personal computers, workstations, servers and supercomputers. The full scope of that project wasn’t realized, but Nvidia did end up making Arm+GPU chips (Tegra/Xaviar and Jetson), for the embedded worlds of mobile, robotics, portable gaming and autonomous vehicles.

In addition to revealing its very own Arm CPU today, Nvidia continues to strengthen its support of Arm-based technologies with partners. Huang announced that together with Amazon Web Services, it is bringing Graviton2 Arm CPUs and Nvidia GPUs together in an EC2 instance, expected later this year. The new instances target demanding cloud workloads, AI, and cloud gaming, said Huang.

Nvidia also announced a partnership with Ampere Computing to create a scientific and cloud computing SDK and reference system. Ampere Computing’s Altra CPU has 80 Neoverse-N1 cores and delivers 285 SPECint rate, “right up there with the highest performance x86,” said Huang.

In addition, Nvidia said it’s entered into a partnership with chip company Marvell to create an edge and enterprise computing SDK and reference system. Marvell’s Octeon chip targets IO storage and 5G processing, and the system is ideal for hyperconverged edge servers, noted Huang.

Absent from today’s news raft was the Cambridge AI research center announced last September, the centerpiece of which is to be an Arm-based supercomputer. Nvidia told HPCwire that the project is still on track, but did not disclose any further details. In October 2020, a company representative told HPCwire “plans are still evolving for the [Cambridge] Arm-based supercomputer,” and said the project was not tied to the closing of the Arm acquisition.

Nvidia also shared that the Cambridge-1 AI SuperPod computer is approaching readiness with updates likely to made during the GTC21 conference proceedings.

With robust support for Arm across its entire ecosystem and the debut of a homegrown Arm CPU, all of the pieces are falling into place for Nvidia’s full-stack datacenter solution. While the pending deal to acquire Arm is still under review, Nvidia is showing it has a strong Arm play with or without actually owning Arm — and that after all is the beauty of the IP licensing model.