Technology isn’t confined to tech companies alone. The digital transformation has changed how the engineers, designers and manufacturers can work on certain construction operations. Even the older companies are now making a shift in this direction which is a welcome sign.

If your company is still using email for communication, provides information and have a website for attracting customers, ERP or CRM and other software tools for managing projects, customers and daily activities, you are on the right path. The world is changing at a fast pace due to advanced technologies and digital transformation.

Well, it is indeed a fact that the construction industry has been slow in adopting new technologies. Businesses have been working at a slower rate towards technology, but these can contribute immensely in modernizing the construction industry. A few changes have already happened, and a few more are expected soon.

Here’s how

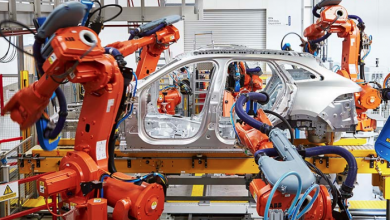

Mobile devices, software applications, BIM and other tools are used in the construction industry. Other modern technologies such as augmented and virtual reality, wearables, Internet of Things, automation, 3D printing and robotics are already making raves for their use in the construction industry, but not many companies are using them as of now.

More and more of these are expected to find a place in the construction industry to resolve the various difficulties they are facing right now. VR, BIM, mobile devices and project management software can pave the way for heightened productivity with features such as new home construction punch list preparation, RFI resolutions and more.

The wearables and drones are utilized for tracking the workers and ensuring their safety. VR can be employed for training in secure environments in addition to robotics and automation in addition to assisting the workers in the daily tasks they need to do.

The implementation of AI for decision making is also rising increasingly. Many companies are using it to determine the best course for proceeding with large scale construction projects and allocation of workforce to parts of the construction so that less time is wasted.

The role of Robotics is also steadily increasing in construction. Despite the complexity of the job, robots can be programmed to carry out mundane and heavy duty tasks, which they have been proven do so very successfully. A multiskill programme is needed for construction workers to keep up with the changes.

Let’s admit that technology will soon become a vital part of the construction projects.

Summing up

The companies incorporating the latest technology into their working style know that they are changing the whole scenario slowly and steadily. Those who haven’t started using it yet are losing out on the evolution taking place.