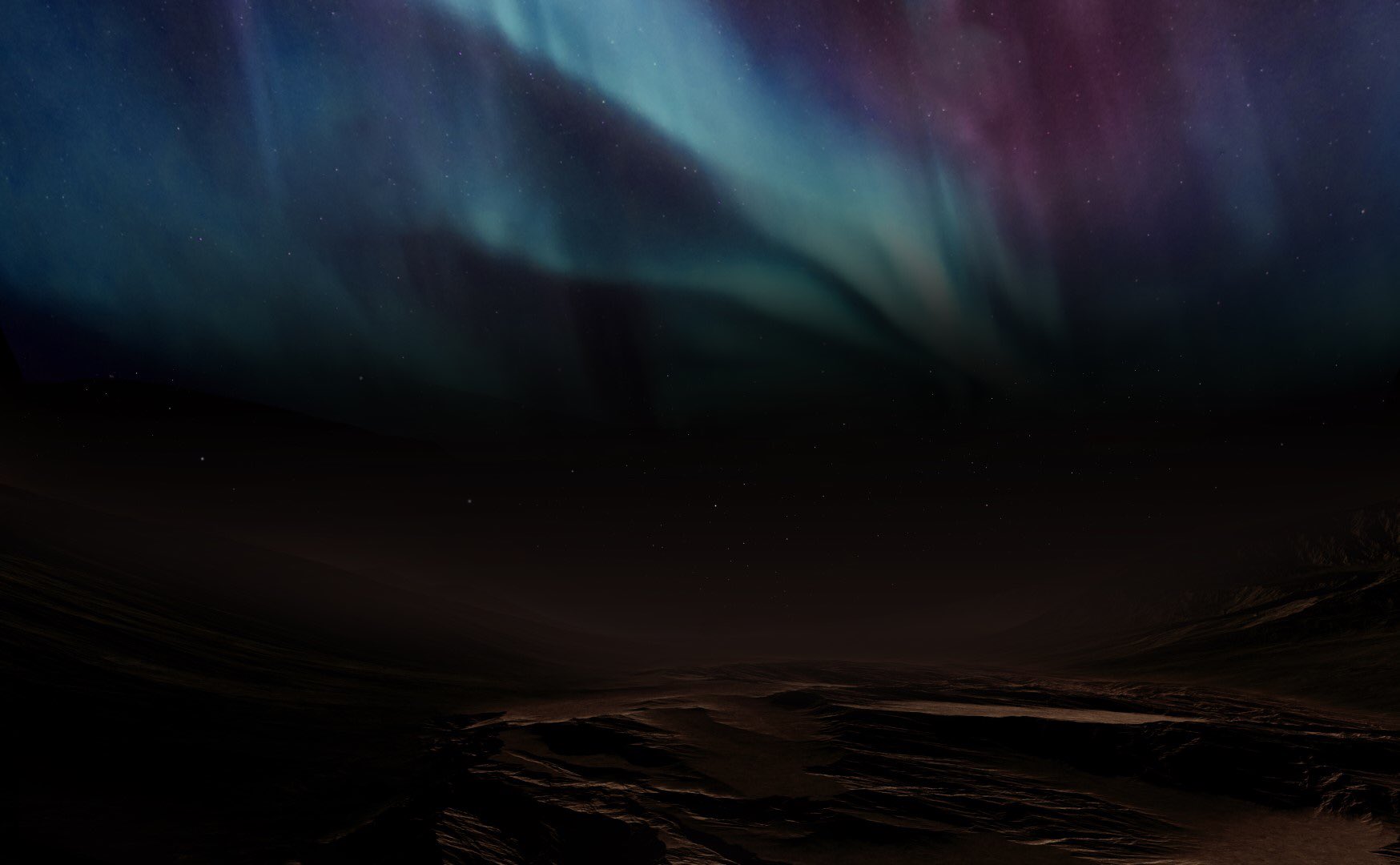

Featured image: An artist’s depiction of the discrete aurora on Mars. (Image credit: Emirates Mars Mission)

The United Arab Emirates’ (UAE) Hope Mars mission made its first major finding just a couple months after arriving at the Red Planet when it snagged unprecedented observations of a tricky aurora.

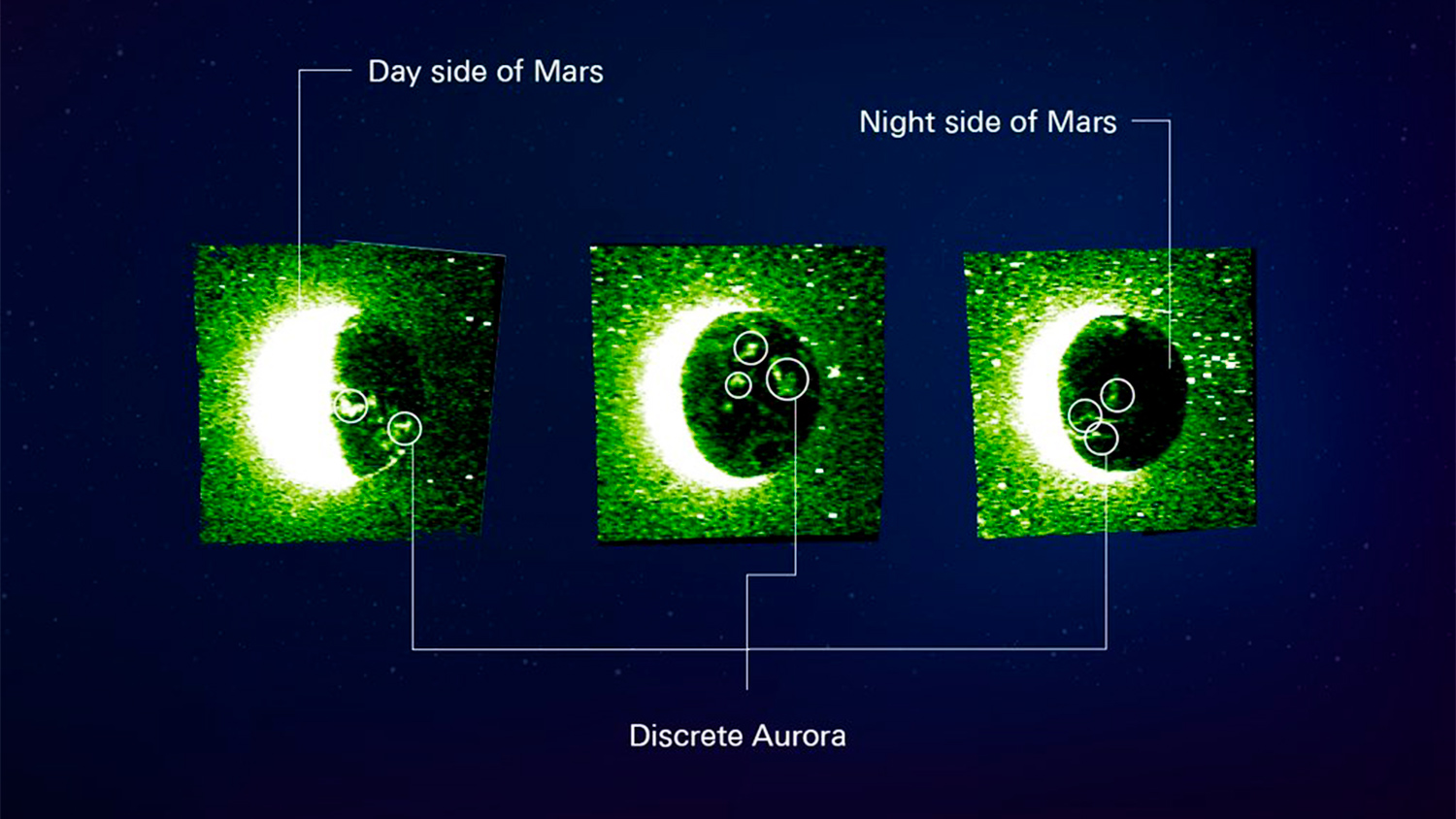

Also known as the Emirates Mars Mission (EMM), Hope is designed to study Mars’ atmosphere across all its layers and at a global scale throughout the course of the year. But the new finding is outside that main science purview and occurred even before the probe’s formal science mission had begun, when scientists were testing the instruments on the spacecraft. In images from one of those instruments, scientists easily spotted the highly localized, nightside aurora that scientists have struggled to study at Mars for decades.

“They’re not easy to catch, and so that’s why seeing them basically right away with EMM was kind of exciting and unexpected,” Justin Deighan, a planetary scientist at the University of Colorado’’ Laboratory for Atmospheric and Space Physics and deputy science lead for the Hope mission, told Space.com. “It’s definitely something that was on our radar, so to speak, but just looking at our first set of nighttime data and saying, ‘Hey, wait a second — is that? — it can’t be — it is!’ — that was a lot of fun.”

Scientists know that Earth’s auroras are tied to the planet’s global magnetic field and are triggered by charged particles from the sun. But the situation is a little different at Mars, where scientists have observed three types of auroras.

One type of Martian aurora occurs exclusively on the daylit side of the planet; the other two occur on the nightside. One of the nighttime phenomena occurs only during extremely strong solar storms and lights up the whole disk. But the discrete aurora, the kind that scientists observed with Hope, isn’t limited to periods of heavy solar activity, instead occuring only in certain patches of the nightside of Mars.

The European Space Agency’s Mars Express spacecraft and NASA’s MAVEN orbiter have both observed the discrete aurora, but not very well. Compared to Hope, those missions have orbited closer to the surface of Mars and seen less of the planet at any given moment, and their instruments haven’t been as powerful.

And it turns out that finding different auroras at Mars than at Earth makes sense, since the magnetic situations on the two planets are very different. “The discrete auroras are tied to an understanding of Mars that only began to really be fleshed out during the space age because it turned out that Mars had a very unusual magnetic field,” Deighan said. “They went there in the ’60s expecting to see something like Earth’s magnetic field, and they found nothing. And then they realized, ‘Wait a second, it’s kind of coming and going, what’s going on?'”

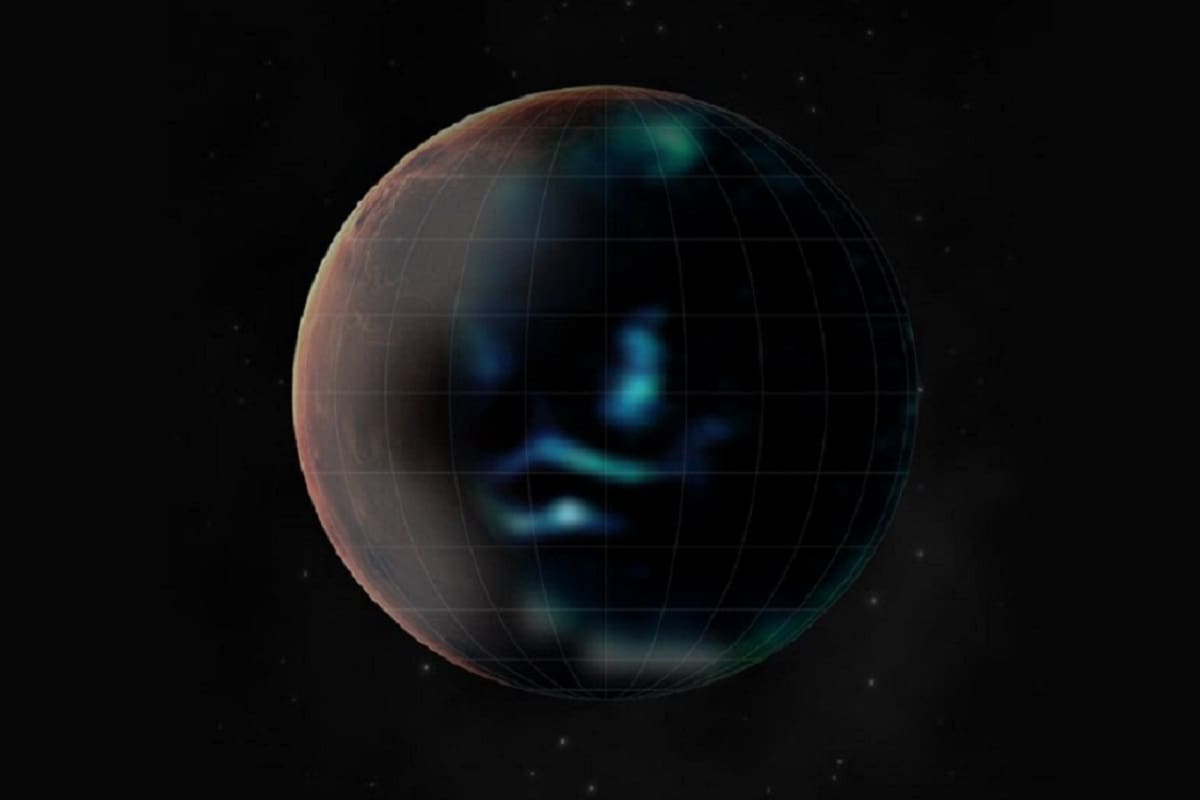

Scientists have made more progress on understanding the strange magnetic field characteristics of the Red Planet because that phenomenon is tied to the Martian crust, which scientists can more easily study. On the planet’s surface, scientists have found patches of rocks that contain the magnetic signature of a global magnetic field that Mars has since lost.

In particular, Deighan said, rocks in the planet’s southern side have intrigued scientists looking for magnetic traces. “Other parts of Mars have been resurfaced, lava flowed on them or big impacts clobbered the magnetic field, heated up the material,” he said. “The southern hemisphere is very very old, it’s from the beginning of the solar system,” leaving those traces undamaged.

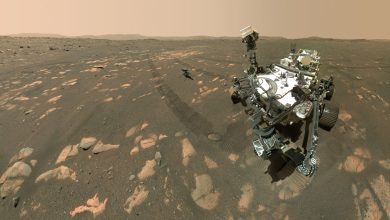

Then, in February, Hope arrived at Mars, becoming the first interplanetary mission from the Arab world. By late March, mission staff slipped the spacecraft into a unique high orbit near the planet’s equator that would give Hope’s instruments a big-picture view of Mars.

Mission scientists, inspired by the history of Red Planet exploration and outstanding questions about the world, had selected three instruments to gather observations about the atmosphere and weather of the Red Planet.

Among those instruments is the Emirates Mars Ultraviolet Spectrometer, or EMUS, which is designed to study thin, vast halo of hydrogen and oxygen surrounding Mars to help scientists understand how those gases slip away from the planet into space, Hessa Al Matroushi, the mission’s science lead, told Space.com. Gathering that data requires a particularly sensitive instrument, and that’s where the scientists got lucky and caught the aurora as well.

“We did anticipate that the instrument would have the potential to do this,” Matroushi said. “It wasn’t designed to do it. But because we do have a mission that is targeting global coverage and we’re looking at Mars from different sides and very frequently within the atmosphere, that enabled us to have such a measurement of discrete auroras, which is very exciting.”

And although the discrete aurora is a subtle phenomenon, its appearance was clear even in the test observations that EMUS first gathered after Hope arrived in its science orbit. “It was basically opening the files and seeing that they were there,” Deighan said.

“Once we overlaid these images of auroras with crustal field maps that have been previously made and they lined up, we said ‘Oh well there you go, it is what it looks like,'” Deighan said, adding that the auroral observations are exactly where we expect them to be.”

For scientists, that correlation gives the discrete aurora images an eerie vibe. “It’s new, but you know what you’re looking at, which is this weird thing we keep coming across with Mars, this combination of the alien and the familiar,” Deighan said.

And now that Hope scientists know these measurements are possible, they expect to gather plenty more observations of the discrete aurora as the mission continues its main science mission, which began May 23 and will last for one Martian year (687 Earth days).

“These are observations that we already have always scheduled within our orbit,” Matroushi said. “There is always the potential that we could catch one [aurora],” and she said the team can also access additional data downlink opportunities to get more observations than expected from the spacecraft.

Although the new observations are the most detailed to date of the discrete aurora, they don’t elucidate precisely what charged particles are creating the effect, Deighan said. He suspects electrons are responsible, although those could be coming either from the sun or from Mars itself. What’s more certain is that their energy is limited. “We know that they’re not super energetic particles, they’re sort of run-of-the-mill energetic particles, if you will,” he said.

Additional observations and more detailed analysis may help scientists tease out where these particles come from. Scientists also aren’t sure what precisely the discrete aurora would look like to human eyes on the surface of Mars. EMUS observes far ultraviolet light beyond the wavelengths human eyes can process. “They’d just give you a bad burn, not actually be visible to your eyes,” Deighan said. “There’s probably a lot of auroras going on at Mars that are not visible to the naked human eye or an astronaut’s eye.”

However, there may still be a visible component to the phenomenon — perhaps red and green and a whitish blue, he said. If so, the result could be stunning, and easier to observe than other Martian aurora that could create a faint glow across the entire sky.

“The discrete aurora would probably be easier to see in the sense that because they have a lot of structure and they’re hanging in the sky, your eye would be able to pick them out,” Deighan said. “It’s hard to pick out a very faintly glowing whole-sky effect, so the discrete aurora would be kind of spectacular.”